Saturday, November 15, 2003

Be Interested To Hear...

What other Patrick O'Brian fans have to say about Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World. How badly have they mangled the books? The fact that the casting looks pretty questionable to this old O'Brian hand, and the fact that they have contrived to combine the first and tenth books in the series does not bode well to my mind.

I know that they left out the fact that Maturin, aside from being a highly skilled doctor, is also one of the Royal Navy's top intelligence operatives. But you don't pick that up from the first book anyway. That comes later. In the first book, all you really know about is his past with the United Irishmen (he is an illegitimate cousin of Lord Edward Fitzgerald, but a staunch anti-Bonapartist).

It has been said by some that the Aubrey/Maturin novels combine to create the best English language novel of the second half of the 20th century. I will not dispute that. In fact, I read the 18 that had been published when I discovered the series in 6 weeks.

Jack and Stephen became great friends of mine in another bleak time in my life. They are characters one comes to care about. Does the movie capture the good fellowship that the books exude? Can it capture the sheer good-natured joy one feels when Jack opens the letter promoting him to command of the Sophie, or the conviviality of Jack and Stephen's first dinner at the tavern, or the hilarity of Killick's constant mutinous grumblings and stupidity?

These novels are special to me. It is not just because I spent a fair amount of my life wearing uniforms that, though somewhat outdated and the wrong branch of the service, would not be unfamiliar to Jack and Stephen, or that I love 18th Century food, and Baroque music, or that O'Brian is a impressively precise in the use of period detail and even expressions (once, I thought his use of the words "medico" and "politico" must be anachronistic, that they surely must b products of WWII slang, only to find that the Oxford English Dictionary hows earliest known use of both words preceeding Jack and Stephen by a century and more). His characters are not the cardboard cutouts of the Hornblower series. O'Brian was not just an historical novelist. He wrote in the grand tradition of Austen and Dickens, with more than an occasional tip of the hat to Shakespeare and Homer. His stuff, unlike Bernard Cornwell's Sharpe novels, which I also like, is literature, and some of the best that we have seen in an age of declining standards.

So what Hollywood has done to it is a matter of great interest to me.

What other Patrick O'Brian fans have to say about Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World. How badly have they mangled the books? The fact that the casting looks pretty questionable to this old O'Brian hand, and the fact that they have contrived to combine the first and tenth books in the series does not bode well to my mind.

I know that they left out the fact that Maturin, aside from being a highly skilled doctor, is also one of the Royal Navy's top intelligence operatives. But you don't pick that up from the first book anyway. That comes later. In the first book, all you really know about is his past with the United Irishmen (he is an illegitimate cousin of Lord Edward Fitzgerald, but a staunch anti-Bonapartist).

It has been said by some that the Aubrey/Maturin novels combine to create the best English language novel of the second half of the 20th century. I will not dispute that. In fact, I read the 18 that had been published when I discovered the series in 6 weeks.

Jack and Stephen became great friends of mine in another bleak time in my life. They are characters one comes to care about. Does the movie capture the good fellowship that the books exude? Can it capture the sheer good-natured joy one feels when Jack opens the letter promoting him to command of the Sophie, or the conviviality of Jack and Stephen's first dinner at the tavern, or the hilarity of Killick's constant mutinous grumblings and stupidity?

These novels are special to me. It is not just because I spent a fair amount of my life wearing uniforms that, though somewhat outdated and the wrong branch of the service, would not be unfamiliar to Jack and Stephen, or that I love 18th Century food, and Baroque music, or that O'Brian is a impressively precise in the use of period detail and even expressions (once, I thought his use of the words "medico" and "politico" must be anachronistic, that they surely must b products of WWII slang, only to find that the Oxford English Dictionary hows earliest known use of both words preceeding Jack and Stephen by a century and more). His characters are not the cardboard cutouts of the Hornblower series. O'Brian was not just an historical novelist. He wrote in the grand tradition of Austen and Dickens, with more than an occasional tip of the hat to Shakespeare and Homer. His stuff, unlike Bernard Cornwell's Sharpe novels, which I also like, is literature, and some of the best that we have seen in an age of declining standards.

So what Hollywood has done to it is a matter of great interest to me.

First Thanksgiving Blog

Unlike last year and just about every other year of my life, my spirits are really not into the holidays this year. But I won't let that stop me from providing commentary on this cherished American holiday. At the very least, I'll republish some of last year's successful Thanksgiving/Christmas blogs, suitably edited. You may have noticed that I did a little of that for Hallowmas and Martinmas.

With about 12 days to go before Thanksgiving, today's Globe offers a photo gallery of Thanksgiving at Plimouth Plantation, a place I greatly enjoy.

Unlike last year and just about every other year of my life, my spirits are really not into the holidays this year. But I won't let that stop me from providing commentary on this cherished American holiday. At the very least, I'll republish some of last year's successful Thanksgiving/Christmas blogs, suitably edited. You may have noticed that I did a little of that for Hallowmas and Martinmas.

With about 12 days to go before Thanksgiving, today's Globe offers a photo gallery of Thanksgiving at Plimouth Plantation, a place I greatly enjoy.

Friday, November 14, 2003

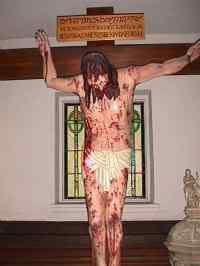

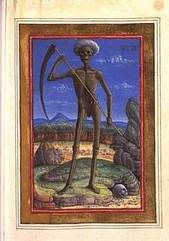

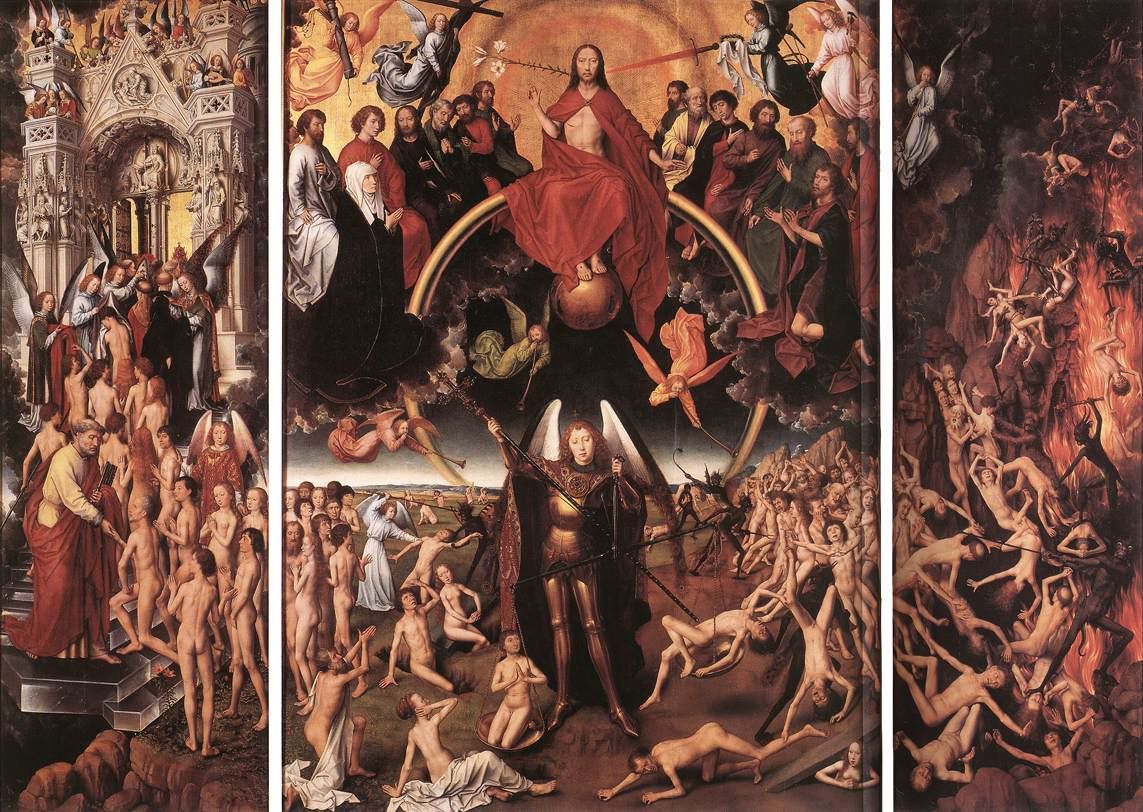

Lord, Mave Mercy

Scott Hahn has a new book out this year, Lord, Have Mercy: The Healing Power of Confession. His theme fits in wonderfully with my November coda on sin, death, judgment, Heaven, Hell, & Purgatory. I also found the book deeply meaningful in a personal sense.

Confession, or the Sacrament of Reconciliation as some prefer to call it, has fallen upon hard times. Hahn cites the fact that about half of our own Roman Catholic priests avail themselves of the Sacrament 1-2 times per year, or almost never. Among the laity, the numbers are much worse. It is not uncommon for people to not make confessions after the first ritual confession in grade school (at least most dioceses have reversed what was the custom in Greater Boston when I was a kid: Eucharist in 2nd Grade, and Confession in 4th).

Many others, me included, only make confessions when things have gone radically wrong in their lives. Very few today even make the once-a-year, before Easter, visit to the confessional.

And the confessions that we do make are often purposefully incomplete. I know that I have, probably even in my first confession, seized upon the "elastic clause" at the end of one's confession: "For these and any other sins I may have committed...".

Of course, my not mentioning certain sins, but letting them slide under the rubric of the elastic clause was not a problem of memory. It was a deliberate lawyerly evasion of having to be embarrassed by talking about things I did not want to talk about.

Lawyerly evasions are not what the Sacrament is all about. It is an opportunity to bring all your sins as best as you can remember them, before God so that He may forgive them. It is a chance for a clean sweep.

Such incomplete confessions are, in fact, sinful. By resorting to them, you are denying yourself the chance at healing. And the sin you are hiding festers. In another book I read this month, Father P.J. Kelly's So High the Price, a story from the writings of St. Antoninus of Florence is recounted:

A young man of 16 concealed a mortal sin in confession. He continued going to Communion week after week, putting off the confession. The weeks turned into months, and the months to years. He was consumed with remorse for the sin. He did many acts of penance. He joined a monastery. He thought that there, at last, he could make his good confession. But the penances he had done had become public knowledge, and from the day that he was welcomed to the monastery, he was treated as someone who had led a publically pure, holy life. He found he could not mention his sin in confession. he made many more flawed confessions. He took the Eucharist many hundreds more times. He fell ill, and thought that this would be an opportunity to make a complete confession. But even then, he could not overcome his pride and confess to the hidden sin of his youth. His fever increased, and he died. His fellows in the monastery treated his remains with great respect. He might have become a local saint, a stop on the monastery tour. Just before the funeral, one of his brothers in the abbey saw a vision of him bound in chains and burning in hell fire. "Do not pray for me. It will not help. I am in Hell." A terrible stench of burning flesh filled the entire monastery.

This stuck with me because, the name changed, the story might well have been about me, until very recently. I have always been very reluctant to confess my faults to another man (or woman). Pride is a terrible sin, and I have more than my share of it.

Hahn follows the modern practice of not trying to frighten people into the confessional. He stresses God's mercy, and the feeling of liberation. Indeed there is a tremendous sense of liberation that follows a complete confession. Scott experienced it in his own life, too.

Hahn also is careful to address one of the canards that is often thrown at the practice of confession: that it was invented by the Church and is not scriptural. He traces it to the penitential practices of the ancient Hebrews, who sacrificed animals and made public declarations of their sins. Such public confessions were the norm in the early Church, as well. Only with the Irish monks who re-introduced civilization to Europe from island fortresses like Iona, Mona, and Skellig Michel did the practice of private confession become common in the Church.

Hahn traces the confession through the binding and loosing power given to Peter and the Apostles. But don't forget what is done in the parable of the Prodigal Son. The prodigal, after coming to his senses, makes a confession to his Father, who forgives him (in fact he does not even let the son finish his rehearsed self-accusation). This story of human and divine mercy is surely the model we are all to follow, and the hope we have about eternal life.

Hahn's book is a treasure trove. He recommends that each person confess regularly: weekly or monthly. He suggests that we develop a relationship with a particular priest as confessor. Of course, that sort of means that you are not using the crutch of complete secrecy that the traditional confessional provides. But it is a trade-off, and one I think worth making.

If you have nothing serious on your conscience, by all means, go and use a confessional. But if something important troubles your soul, take it to a priest face-to-face (a priest who believes in confession, of course). Even if you think your part in a troubling problem is not sinful, still talk it over with a trusted priest. He may see sin in your actions that you can't perceive.

Hahn provides numerous confessional aids, as well. He provides a form for an examination of conscience, based on the Ten Commandments. But not everyone agrees with this approach. When my confessor saw me pull out a paper with all my sins written o it, he was horrified. "Don't do one of those again. When we're done, tear it up into small pieces. You know in your heart and I your mind what you have done wrong." So opinions vary on the usefulness of this device.

Hahn provides a form for confession under the new rite, which I don't use, and three different Acts of Contrition, a prayer for after confession, and the text (though I dislike the translation) of the 50/51st Psalm, as well as the format for the Divine Mercy chaplet, with which I was completely unfamiliar until this past summer.

And Hahn has some good ideas for bringing forgiveness into the home. "Be merciful , even as your Father is merciful." For no venue is more likely to be a breeding ground for sins petty and great than the home, the place you are in contact with people you must live with intimately. "We, too, must find ways-concrete, specific ways- to bring mercy to our homes, our workplaces, and our neighborhoods. For we cannot keep God's mercy to ourselves unless we give it away to others."

Hahn posits a solution in the form of a "family jubilee" based on the ancient Hebrew custom of a year of mercy. In the family jubilee, all transgressions may be confessed without fear of repercussion. He says it works in his family.

Hahn concludes:

"We need confession. The longing for mercy that consumed countless canonized saints...has not diminished in the least. Indeed, it has grown stronger. For we live in anxious times, when many people feel locked out of the family home--the home of their Father God. And for those who want to get back to the hearth and the table, confession is the key. Better still, the confessional is the open doorway to the only home that will ever satisfy us."

Hahn has said things in this book that modern Catholics, priests as well as laity, need to listen to. Don't allow the opportunity that confession provides to sweep away the burden of sin to pass until it is too late. Seek it out from a trusted, wise priest, who believes in sin and the power of healing in sacramental confession. Acts of Contrition and self-imposed penances are not enough.

I know it is hard. It is so, so hard. I paced up and down on the street before hand like George Bailey in It's a Wonderful Life before he drops by to visit Mary. I had to work up the nerve to go in. But absolution, the taking away of so many encrusted layers and interlocking networks of sin feels so wonderful once it is given. I found myself humming the Notre Dame fight song, and I don't even like Notre Dame.

Scott Hahn has a new book out this year, Lord, Have Mercy: The Healing Power of Confession. His theme fits in wonderfully with my November coda on sin, death, judgment, Heaven, Hell, & Purgatory. I also found the book deeply meaningful in a personal sense.

Confession, or the Sacrament of Reconciliation as some prefer to call it, has fallen upon hard times. Hahn cites the fact that about half of our own Roman Catholic priests avail themselves of the Sacrament 1-2 times per year, or almost never. Among the laity, the numbers are much worse. It is not uncommon for people to not make confessions after the first ritual confession in grade school (at least most dioceses have reversed what was the custom in Greater Boston when I was a kid: Eucharist in 2nd Grade, and Confession in 4th).

Many others, me included, only make confessions when things have gone radically wrong in their lives. Very few today even make the once-a-year, before Easter, visit to the confessional.

And the confessions that we do make are often purposefully incomplete. I know that I have, probably even in my first confession, seized upon the "elastic clause" at the end of one's confession: "For these and any other sins I may have committed...".

Of course, my not mentioning certain sins, but letting them slide under the rubric of the elastic clause was not a problem of memory. It was a deliberate lawyerly evasion of having to be embarrassed by talking about things I did not want to talk about.

Lawyerly evasions are not what the Sacrament is all about. It is an opportunity to bring all your sins as best as you can remember them, before God so that He may forgive them. It is a chance for a clean sweep.

Such incomplete confessions are, in fact, sinful. By resorting to them, you are denying yourself the chance at healing. And the sin you are hiding festers. In another book I read this month, Father P.J. Kelly's So High the Price, a story from the writings of St. Antoninus of Florence is recounted:

A young man of 16 concealed a mortal sin in confession. He continued going to Communion week after week, putting off the confession. The weeks turned into months, and the months to years. He was consumed with remorse for the sin. He did many acts of penance. He joined a monastery. He thought that there, at last, he could make his good confession. But the penances he had done had become public knowledge, and from the day that he was welcomed to the monastery, he was treated as someone who had led a publically pure, holy life. He found he could not mention his sin in confession. he made many more flawed confessions. He took the Eucharist many hundreds more times. He fell ill, and thought that this would be an opportunity to make a complete confession. But even then, he could not overcome his pride and confess to the hidden sin of his youth. His fever increased, and he died. His fellows in the monastery treated his remains with great respect. He might have become a local saint, a stop on the monastery tour. Just before the funeral, one of his brothers in the abbey saw a vision of him bound in chains and burning in hell fire. "Do not pray for me. It will not help. I am in Hell." A terrible stench of burning flesh filled the entire monastery.

This stuck with me because, the name changed, the story might well have been about me, until very recently. I have always been very reluctant to confess my faults to another man (or woman). Pride is a terrible sin, and I have more than my share of it.

Hahn follows the modern practice of not trying to frighten people into the confessional. He stresses God's mercy, and the feeling of liberation. Indeed there is a tremendous sense of liberation that follows a complete confession. Scott experienced it in his own life, too.

Hahn also is careful to address one of the canards that is often thrown at the practice of confession: that it was invented by the Church and is not scriptural. He traces it to the penitential practices of the ancient Hebrews, who sacrificed animals and made public declarations of their sins. Such public confessions were the norm in the early Church, as well. Only with the Irish monks who re-introduced civilization to Europe from island fortresses like Iona, Mona, and Skellig Michel did the practice of private confession become common in the Church.

Hahn traces the confession through the binding and loosing power given to Peter and the Apostles. But don't forget what is done in the parable of the Prodigal Son. The prodigal, after coming to his senses, makes a confession to his Father, who forgives him (in fact he does not even let the son finish his rehearsed self-accusation). This story of human and divine mercy is surely the model we are all to follow, and the hope we have about eternal life.

Hahn's book is a treasure trove. He recommends that each person confess regularly: weekly or monthly. He suggests that we develop a relationship with a particular priest as confessor. Of course, that sort of means that you are not using the crutch of complete secrecy that the traditional confessional provides. But it is a trade-off, and one I think worth making.

If you have nothing serious on your conscience, by all means, go and use a confessional. But if something important troubles your soul, take it to a priest face-to-face (a priest who believes in confession, of course). Even if you think your part in a troubling problem is not sinful, still talk it over with a trusted priest. He may see sin in your actions that you can't perceive.

Hahn provides numerous confessional aids, as well. He provides a form for an examination of conscience, based on the Ten Commandments. But not everyone agrees with this approach. When my confessor saw me pull out a paper with all my sins written o it, he was horrified. "Don't do one of those again. When we're done, tear it up into small pieces. You know in your heart and I your mind what you have done wrong." So opinions vary on the usefulness of this device.

Hahn provides a form for confession under the new rite, which I don't use, and three different Acts of Contrition, a prayer for after confession, and the text (though I dislike the translation) of the 50/51st Psalm, as well as the format for the Divine Mercy chaplet, with which I was completely unfamiliar until this past summer.

And Hahn has some good ideas for bringing forgiveness into the home. "Be merciful , even as your Father is merciful." For no venue is more likely to be a breeding ground for sins petty and great than the home, the place you are in contact with people you must live with intimately. "We, too, must find ways-concrete, specific ways- to bring mercy to our homes, our workplaces, and our neighborhoods. For we cannot keep God's mercy to ourselves unless we give it away to others."

Hahn posits a solution in the form of a "family jubilee" based on the ancient Hebrew custom of a year of mercy. In the family jubilee, all transgressions may be confessed without fear of repercussion. He says it works in his family.

Hahn concludes:

"We need confession. The longing for mercy that consumed countless canonized saints...has not diminished in the least. Indeed, it has grown stronger. For we live in anxious times, when many people feel locked out of the family home--the home of their Father God. And for those who want to get back to the hearth and the table, confession is the key. Better still, the confessional is the open doorway to the only home that will ever satisfy us."

Hahn has said things in this book that modern Catholics, priests as well as laity, need to listen to. Don't allow the opportunity that confession provides to sweep away the burden of sin to pass until it is too late. Seek it out from a trusted, wise priest, who believes in sin and the power of healing in sacramental confession. Acts of Contrition and self-imposed penances are not enough.

I know it is hard. It is so, so hard. I paced up and down on the street before hand like George Bailey in It's a Wonderful Life before he drops by to visit Mary. I had to work up the nerve to go in. But absolution, the taking away of so many encrusted layers and interlocking networks of sin feels so wonderful once it is given. I found myself humming the Notre Dame fight song, and I don't even like Notre Dame.

Psalm 6

The First Penitential Psalm

Friday is traditionally a penitential day. So today, I offer the first of the Seven Penitential Psalms, Psalm 6 (Dhouay-Rheims Bible On Line, with the verse numbers removed, and a few jarring translations replaced):

O Lord, rebuke me not in thy indignation, nor chastise me in thy wrath.

Have mercy on me, O Lord, for I am weak: heal me, O Lord, for my bones are troubled.

And my soul is troubled exceedingly: but thou, O Lord, how long?

Turn to me, O Lord, and deliver my soul: O save me for thy mercy's sake.

For there is no one in death, that is mindful of thee: and who shall confess to thee in hell?

I have laboured in my groanings, every night I wash my bed with tears: I water my couch with sorrow.

My eye is troubled through Your indignation: I have grown old amongst all my enemies.

Depart from me, all ye evildoers: for the Lord hath heard the voice of my weeping.

The Lord hath heard my supplication: the Lord hath received my prayer.

Let all my enemies be ashamed, and be very much troubled: let them be turned back, and be ashamed very speedily.

This is a pretty pugnacious effort in asking for mercy. "Lord help me, and humiliate my enemies." There are many places in the Psalms where the request from the Psalmist is to not just overcome those who seek his undoing and thwart them, but to completely destroy and humiliate them once and for all. This is one of the most mild instances. I recall another one where dogs are to lick the poured-out blood of the Psalmist's enemies.

I have my doubts how far this can be accepted as Christian doctrine, unless you read the Devil for the term "evildoers." And frankly, that is not really what the Psalmist has in mind. He does seem to be asking for the destruction of his earthly enemies, without much in the way of turning the other cheek. Recall, however, that this was in the old covenant. Christ modified that covenant, and substituted a new, more loving and forgiving one.

It might be more appropriate for the Christian reading this Psalm to pray briefly after reading it: "Lord, have mercy on me, a sinner. Help me in my distress. Help me to forgive those who persecute me. Help us to live together in harmony through Your Gospel."

The First Penitential Psalm

Friday is traditionally a penitential day. So today, I offer the first of the Seven Penitential Psalms, Psalm 6 (Dhouay-Rheims Bible On Line, with the verse numbers removed, and a few jarring translations replaced):

O Lord, rebuke me not in thy indignation, nor chastise me in thy wrath.

Have mercy on me, O Lord, for I am weak: heal me, O Lord, for my bones are troubled.

And my soul is troubled exceedingly: but thou, O Lord, how long?

Turn to me, O Lord, and deliver my soul: O save me for thy mercy's sake.

For there is no one in death, that is mindful of thee: and who shall confess to thee in hell?

I have laboured in my groanings, every night I wash my bed with tears: I water my couch with sorrow.

My eye is troubled through Your indignation: I have grown old amongst all my enemies.

Depart from me, all ye evildoers: for the Lord hath heard the voice of my weeping.

The Lord hath heard my supplication: the Lord hath received my prayer.

Let all my enemies be ashamed, and be very much troubled: let them be turned back, and be ashamed very speedily.

This is a pretty pugnacious effort in asking for mercy. "Lord help me, and humiliate my enemies." There are many places in the Psalms where the request from the Psalmist is to not just overcome those who seek his undoing and thwart them, but to completely destroy and humiliate them once and for all. This is one of the most mild instances. I recall another one where dogs are to lick the poured-out blood of the Psalmist's enemies.

I have my doubts how far this can be accepted as Christian doctrine, unless you read the Devil for the term "evildoers." And frankly, that is not really what the Psalmist has in mind. He does seem to be asking for the destruction of his earthly enemies, without much in the way of turning the other cheek. Recall, however, that this was in the old covenant. Christ modified that covenant, and substituted a new, more loving and forgiving one.

It might be more appropriate for the Christian reading this Psalm to pray briefly after reading it: "Lord, have mercy on me, a sinner. Help me in my distress. Help me to forgive those who persecute me. Help us to live together in harmony through Your Gospel."

Wednesday, November 12, 2003

Bringing Us Up To Date

There are two interesting developments on the Archbishop Sean front.

1) He is back-tracking hard on the benefits for gay couples issue. Bishop Reilly's statement ought not to have been made, especially on behalf of all the other bishops of Massachusetts.

2) He will be meeting with the VOTF. There is nothing necessarily sinister here. Cardinal Law met with them, too. At the time, one could legitimately fear that Law might have made an alliance with the heterodox in VOTF to save his job. Archbishop Sean is in a much stronger position than Cardinal Law was at this time last year.

However, one wonders if, despite the relative strength of his position, he will nonetheless give them what they want: lifting the ban on use of parish property for meetings. That would be unwise. Better to make it clear that VOTF is not the thing. even though its appeal is diminishing, now that the pervert priest crisis is winding down here in Boston. No sense breathing new life into that organization, which is what lifting the ban would do.

I still lament the inability of conservative/orthodox/traditionalist Catholics to come up with a grassroots organization to counter VOTF, one not identified with defending Cardinal Law, et al.

And the bishops are meeting again. Why does this fill me with trepidation? They certainly will not be doing anything useful, like stamping out dissent and homosexuality in the priesthood/sisterhood/theological community/diocesan and national staffs. There is word that they are thinking about sanctions for pro-abortion politicians. Want to bet nothing will come of it, or if something does come out, it will be toothless? Excommunicate Ted Kennedy, Chris Dodd, John Kerry, Ed Markey, et al.? A dog will learn how to play the Goldberg Variations perfectly before that happens.

There are two interesting developments on the Archbishop Sean front.

1) He is back-tracking hard on the benefits for gay couples issue. Bishop Reilly's statement ought not to have been made, especially on behalf of all the other bishops of Massachusetts.

2) He will be meeting with the VOTF. There is nothing necessarily sinister here. Cardinal Law met with them, too. At the time, one could legitimately fear that Law might have made an alliance with the heterodox in VOTF to save his job. Archbishop Sean is in a much stronger position than Cardinal Law was at this time last year.

However, one wonders if, despite the relative strength of his position, he will nonetheless give them what they want: lifting the ban on use of parish property for meetings. That would be unwise. Better to make it clear that VOTF is not the thing. even though its appeal is diminishing, now that the pervert priest crisis is winding down here in Boston. No sense breathing new life into that organization, which is what lifting the ban would do.

I still lament the inability of conservative/orthodox/traditionalist Catholics to come up with a grassroots organization to counter VOTF, one not identified with defending Cardinal Law, et al.

And the bishops are meeting again. Why does this fill me with trepidation? They certainly will not be doing anything useful, like stamping out dissent and homosexuality in the priesthood/sisterhood/theological community/diocesan and national staffs. There is word that they are thinking about sanctions for pro-abortion politicians. Want to bet nothing will come of it, or if something does come out, it will be toothless? Excommunicate Ted Kennedy, Chris Dodd, John Kerry, Ed Markey, et al.? A dog will learn how to play the Goldberg Variations perfectly before that happens.

Requiescat In Pace

Comedian Art Carney died Sunday at the age of 85, joining a long list of distinguished celebrities who have died this year. I remember watching re-runs of The Honeymooners as a child. Carney stole the show regularly, often with wonderful physical humor. I was deeply moved by the ending of the movie he won an Oscar for, Harry and Tonto. Carney had his problems in life. Let us pray that God has been merciful to him. Requiescat in pace.

Comedian Art Carney died Sunday at the age of 85, joining a long list of distinguished celebrities who have died this year. I remember watching re-runs of The Honeymooners as a child. Carney stole the show regularly, often with wonderful physical humor. I was deeply moved by the ending of the movie he won an Oscar for, Harry and Tonto. Carney had his problems in life. Let us pray that God has been merciful to him. Requiescat in pace.

Tuesday, November 11, 2003

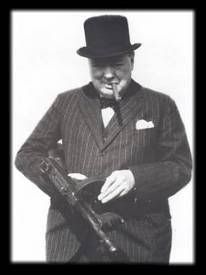

General George Patton

Fittingly, on this day in 1885, General George S. Patton was born. He served on the staff of Black Jack Pershing in Mexico and in World War I, and was an advocate of armored warfare theory before World War II. He was given the job of taking over a defeated US corps in North Africa, and turned it into a first-class unit. He commanded the Seventh Army in the invasion of Sicily, and took Messina. Some bad publicity shelved him during the D-Day invasion, but he was soon given the command of the US Third Army, and lead the breakout from the Normandy/Brittany area across France. His forces turned 90 degrees to respond to the German offensive in Demember, 1944. His forces were pushing past the limits of the US zone of occupation when the war ended. in peacetime, his hostile and realistic attitude towards the Soviets earned him early retirement. But he died as the result of a car crash in Germany in December, 1946.

Fittingly, on this day in 1885, General George S. Patton was born. He served on the staff of Black Jack Pershing in Mexico and in World War I, and was an advocate of armored warfare theory before World War II. He was given the job of taking over a defeated US corps in North Africa, and turned it into a first-class unit. He commanded the Seventh Army in the invasion of Sicily, and took Messina. Some bad publicity shelved him during the D-Day invasion, but he was soon given the command of the US Third Army, and lead the breakout from the Normandy/Brittany area across France. His forces turned 90 degrees to respond to the German offensive in Demember, 1944. His forces were pushing past the limits of the US zone of occupation when the war ended. in peacetime, his hostile and realistic attitude towards the Soviets earned him early retirement. But he died as the result of a car crash in Germany in December, 1946.

How "Tommy Atkins" Got His Name

From The Imperial War Museum:

The origins of the term "Tommy Atkins" as a nickname for the British (or rather English) soldier are still nebulous and indeed disputed. A widely held theory is that the Duke of Wellington himself chose the name in 1843....

The Duke of Wellington's use of the expression is said to have been inspired by an incident during the Battle of Boxtel (Holland) against the French on September 1794. Wellington, (then Arthur Wellesley), led the 33rd Regiment of Foot, and at the end of the engagement Wellesley spotted among the wounded the right-hand-man of the Grenadier Company, a man of 6 ft 3 inches with twenty years' service. He was dying of three wounds - a sabre slash in the head, a bayonet thrust in the breast, and a bullet through the lungs. He looked up at Wellesley and apparently thought his commander was concerned, because he said, "It's alright sir. It's all in a day's work", and then died.

The man's name was Private Thomas Atkins, and his heroism is said to have left such an impression on Wellington, that when he was Commander in Chief of the British Army he recalled the name and used it as a specimen on a new set of soldiers' documents sent to him at Walmer Castle for approval.

From The Imperial War Museum:

The origins of the term "Tommy Atkins" as a nickname for the British (or rather English) soldier are still nebulous and indeed disputed. A widely held theory is that the Duke of Wellington himself chose the name in 1843....

The Duke of Wellington's use of the expression is said to have been inspired by an incident during the Battle of Boxtel (Holland) against the French on September 1794. Wellington, (then Arthur Wellesley), led the 33rd Regiment of Foot, and at the end of the engagement Wellesley spotted among the wounded the right-hand-man of the Grenadier Company, a man of 6 ft 3 inches with twenty years' service. He was dying of three wounds - a sabre slash in the head, a bayonet thrust in the breast, and a bullet through the lungs. He looked up at Wellesley and apparently thought his commander was concerned, because he said, "It's alright sir. It's all in a day's work", and then died.

The man's name was Private Thomas Atkins, and his heroism is said to have left such an impression on Wellington, that when he was Commander in Chief of the British Army he recalled the name and used it as a specimen on a new set of soldiers' documents sent to him at Walmer Castle for approval.

Remembrance Day

In the United Kingdom and its former colonies, today is Remembrance Day, essentially Memeorial Day for the war dead of Britain, Canada, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand , South Africa, and India.

We in the US think of our British cousins, when we do, as stalwart allies in common efforts. But Britain has gone it alone without the US when it was convinced the cause of freedom required it.

It was British redcoats who hemmed in Louis XIV, thwarted Bonaparte at Waterloo, and curbed the Czar in the Crimea. Britain brought civilization to a sizeable chunk of the globe. Britain along with France held the Kaisar's army at bay until the US deemed it appropriate to join in the fray. Britain stood alone against Hitler and Mussolini in 1940 and 1941. British troops fought Japan in Asia, and fought alongside us in Korea, Serbia, the Iraqi desert, and in Afghanistan. They will be alongside us when we depose the tyrant in Iraq next year. They stood shoulder-to-shoulder with us for 40 years, ready to stop a Soviet blitzkrieg into Western Europe.

This is a day to remember also Tommy Atkins, soldiering on at Malplaquet and Ramillies, Fontenoy and Culloden, Minden, Quebec, Warburg, Plassey, and Wilhelmstahl, Bunker Hill, Long Island, Brandywine, Germantown, Camden, and Guilford Courthouse, Talavera, Busaco, Fuentes de Honoro, Cuidad Roderigo, Badajoz, Salamanca, Vittoria, the Pyrennes, Quatre Bras and Waterloo, Sevastopol, the Sepoy Mutiny, Roarke's Drift, Ladysmith, and Omdurman, Ypres, Gallipoli, the Marne, and the Somme, Dunkirk, Crete, Gazala, Crusader, El Alamien, Dieppe, Goodwood, Epsom, and Arnhem, Goose Green and Desert Sabre.

As an honorary member of the officers' messes of the Royal Anglians, Royal Welsh Fusileers, the Black Watch, and Connaught Rangers, I have special reason to observe this day. This is a day to remember those who have fought for our sakes, even long before we were born.

In the United Kingdom and its former colonies, today is Remembrance Day, essentially Memeorial Day for the war dead of Britain, Canada, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand , South Africa, and India.

We in the US think of our British cousins, when we do, as stalwart allies in common efforts. But Britain has gone it alone without the US when it was convinced the cause of freedom required it.

It was British redcoats who hemmed in Louis XIV, thwarted Bonaparte at Waterloo, and curbed the Czar in the Crimea. Britain brought civilization to a sizeable chunk of the globe. Britain along with France held the Kaisar's army at bay until the US deemed it appropriate to join in the fray. Britain stood alone against Hitler and Mussolini in 1940 and 1941. British troops fought Japan in Asia, and fought alongside us in Korea, Serbia, the Iraqi desert, and in Afghanistan. They will be alongside us when we depose the tyrant in Iraq next year. They stood shoulder-to-shoulder with us for 40 years, ready to stop a Soviet blitzkrieg into Western Europe.

This is a day to remember also Tommy Atkins, soldiering on at Malplaquet and Ramillies, Fontenoy and Culloden, Minden, Quebec, Warburg, Plassey, and Wilhelmstahl, Bunker Hill, Long Island, Brandywine, Germantown, Camden, and Guilford Courthouse, Talavera, Busaco, Fuentes de Honoro, Cuidad Roderigo, Badajoz, Salamanca, Vittoria, the Pyrennes, Quatre Bras and Waterloo, Sevastopol, the Sepoy Mutiny, Roarke's Drift, Ladysmith, and Omdurman, Ypres, Gallipoli, the Marne, and the Somme, Dunkirk, Crete, Gazala, Crusader, El Alamien, Dieppe, Goodwood, Epsom, and Arnhem, Goose Green and Desert Sabre.

As an honorary member of the officers' messes of the Royal Anglians, Royal Welsh Fusileers, the Black Watch, and Connaught Rangers, I have special reason to observe this day. This is a day to remember those who have fought for our sakes, even long before we were born.

Veterans' Day

As the importance of the anniversary of the end of Waorld War I declined after the Second World War, the observance of November 11th in the United States was transformed into a day to honor those who have served the US in uniform. On this day, the president participates in services at Arlington National Cemetery, laying a wreath at the Grave of the Unknown Soldier. All across America, small ceremonies are held to remember our veterans.

But for most Americans, with financial markets, banks, post offices, schools, and government offices closed, it is a day to get a head start on Christmas shopping, or get more sleep. That this day has been so transformed is a sad commentary on our culture. It should be a day for thanking our veterans, and remembering what they lived through for our sakes.

In modern society, a small percentage of young men serve in uniform so that, when needed, they can protect their country and its people. The military has been our safeguard since 1775, earlier if you count our struggles with the French and their Indian allies.

In that time, the honor roll of battles is a long one. From Trenton, Princeton, Saratoga, Stony Point, Vincennes, and Yorktown to Lake Erie, on the USS Constitution, and at New Orleans, to the Alamo, to Chapultapec to Vicksburg, Gettysburg, Lookout Mountain, Cold Harbor, Petersburg and Appomattox, to San Juan Hill and Manila Bay, to the Western Front in 1918, to Midway, Tunisia, Sicily, Monte Cassino, Omaha Beach, Nijmegen Bridge, the Battle of the Bulge, the Hurtgen Forest, the Crossing of the Rhine, Guadalcanal, Okinawa, Iwo Jima, Pusan, Inchon, the Chosin Reservoir, Khe Sanh, Ia Drang, Tet, Libya, Grenada, Panama, Desert Storm, Serbia, and on the USS Cole, in Afghanistan, and at ten thousand other places, the American serviceman has answered the call to arms and served with distinction.

My own father's World War II experience is probably fairly typical. He enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1942, at the age of 22. He was assigned as base security at Alamagordo, New Mexico, guarding an airstrip in some way related to the Manhattan Project (but he didn't know that, then). For more than two years, his biggest worries were rattlesnakes, and convincing the PX clerk that, when he asked for "tonic," he wanted Coca Cola, not hair tonic (actually my father preferred a noxious brew you can still buy called Moxie). The Battle of the Bulge created a huge need for combat infantry replacements, so in early 1945, he found himself on a liberty ship heading for Germany. He was assigned to the 69th Infantry Division, and took part in the battle for Germany. He won a Bronze Star for pulling a wounded comrade to cover while under enemy fire. In April, his luck ran out. While moving through the supposedly cleared town of Wiessenfels, he took a sniper's bullet an inch from his lower spine. He spent a few months in hospital in England, and then was sent back to Germany until he was demobilized. While guarding a supply train, he was almost murdered by Russian soldiers intent on looting the train. After a liberty ship trip back to the US, he married my mom. The bullet remained in him, and began to give him difficulty again just a few months before he died (of a heart attack) in 1989.

If any generation of American servicemen had not done their duty, one shudders to think what would have become of the American experiment in democracy and capitalism.

Other cultures have held ours in contempt, and felt we would not make real warriors. As David Hackett Fischer wrote in Paul Revere's Ride,

The Regulars of the British Army and the citizen soldiers of Massachusetts looked upon military affairs in very different ways. New England farmers did not think of war as a game, or a feudal ritual, or an instrument of state power, or a bloodsport for bored country gentlemen...In 1775, many men of Massachusetts had been to war. They knew its horrors from personal experience. With a few exceptions, they thought of fighting as a dirty business that had to be done from time to time if good men were to survive in a world of evil....[M]ost New Englanders were not pacifists themselves. Once committed to what they regarded as a just and necessary war, these sons of Puritans hardened their hearts and became the most implacable of foes. Their many enemies who lived by a warrior- ethic always underestimated them, as a long parade of Indian braves, French aristocrats, British redcoats, Southern planters, German fascists, Japanese militarists, Marxist idealogues, and Arab adventurers have invariabley discovered to their heavy cost.

So for those who have served our country in uniform, we thank you for that service. American democracy depended upon you, and you came through. America is a better place for your service, though the memories may be painful to you, even more than 50 years later.

As the importance of the anniversary of the end of Waorld War I declined after the Second World War, the observance of November 11th in the United States was transformed into a day to honor those who have served the US in uniform. On this day, the president participates in services at Arlington National Cemetery, laying a wreath at the Grave of the Unknown Soldier. All across America, small ceremonies are held to remember our veterans.

But for most Americans, with financial markets, banks, post offices, schools, and government offices closed, it is a day to get a head start on Christmas shopping, or get more sleep. That this day has been so transformed is a sad commentary on our culture. It should be a day for thanking our veterans, and remembering what they lived through for our sakes.

In modern society, a small percentage of young men serve in uniform so that, when needed, they can protect their country and its people. The military has been our safeguard since 1775, earlier if you count our struggles with the French and their Indian allies.

In that time, the honor roll of battles is a long one. From Trenton, Princeton, Saratoga, Stony Point, Vincennes, and Yorktown to Lake Erie, on the USS Constitution, and at New Orleans, to the Alamo, to Chapultapec to Vicksburg, Gettysburg, Lookout Mountain, Cold Harbor, Petersburg and Appomattox, to San Juan Hill and Manila Bay, to the Western Front in 1918, to Midway, Tunisia, Sicily, Monte Cassino, Omaha Beach, Nijmegen Bridge, the Battle of the Bulge, the Hurtgen Forest, the Crossing of the Rhine, Guadalcanal, Okinawa, Iwo Jima, Pusan, Inchon, the Chosin Reservoir, Khe Sanh, Ia Drang, Tet, Libya, Grenada, Panama, Desert Storm, Serbia, and on the USS Cole, in Afghanistan, and at ten thousand other places, the American serviceman has answered the call to arms and served with distinction.

My own father's World War II experience is probably fairly typical. He enlisted in the Army Air Corps in 1942, at the age of 22. He was assigned as base security at Alamagordo, New Mexico, guarding an airstrip in some way related to the Manhattan Project (but he didn't know that, then). For more than two years, his biggest worries were rattlesnakes, and convincing the PX clerk that, when he asked for "tonic," he wanted Coca Cola, not hair tonic (actually my father preferred a noxious brew you can still buy called Moxie). The Battle of the Bulge created a huge need for combat infantry replacements, so in early 1945, he found himself on a liberty ship heading for Germany. He was assigned to the 69th Infantry Division, and took part in the battle for Germany. He won a Bronze Star for pulling a wounded comrade to cover while under enemy fire. In April, his luck ran out. While moving through the supposedly cleared town of Wiessenfels, he took a sniper's bullet an inch from his lower spine. He spent a few months in hospital in England, and then was sent back to Germany until he was demobilized. While guarding a supply train, he was almost murdered by Russian soldiers intent on looting the train. After a liberty ship trip back to the US, he married my mom. The bullet remained in him, and began to give him difficulty again just a few months before he died (of a heart attack) in 1989.

If any generation of American servicemen had not done their duty, one shudders to think what would have become of the American experiment in democracy and capitalism.

Other cultures have held ours in contempt, and felt we would not make real warriors. As David Hackett Fischer wrote in Paul Revere's Ride,

The Regulars of the British Army and the citizen soldiers of Massachusetts looked upon military affairs in very different ways. New England farmers did not think of war as a game, or a feudal ritual, or an instrument of state power, or a bloodsport for bored country gentlemen...In 1775, many men of Massachusetts had been to war. They knew its horrors from personal experience. With a few exceptions, they thought of fighting as a dirty business that had to be done from time to time if good men were to survive in a world of evil....[M]ost New Englanders were not pacifists themselves. Once committed to what they regarded as a just and necessary war, these sons of Puritans hardened their hearts and became the most implacable of foes. Their many enemies who lived by a warrior- ethic always underestimated them, as a long parade of Indian braves, French aristocrats, British redcoats, Southern planters, German fascists, Japanese militarists, Marxist idealogues, and Arab adventurers have invariabley discovered to their heavy cost.

So for those who have served our country in uniform, we thank you for that service. American democracy depended upon you, and you came through. America is a better place for your service, though the memories may be painful to you, even more than 50 years later.

Armistice Day

At eleven minutes after the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, World War I ended. It was a war entered into by most of Europe with jubilation 4 years before. The astonishing slaughter of the trenches in pointless battles at Verdun, Ypres, the Somme, the Argonne, the Marne, and Gallipoli turned the jubilation into bleak despair as Europe's generals could think of nothing better than to have an entire generation slaughtered and maimed, while their governments ginned up what popular enthusiasm they could by proclaiming it a war to end all wars.

World War I ended Europe's dominance of the world. It's outcome abruptly ended the rule of the Romanovs, Habsburgs, and Hohenzollerns. It brought the menace of communism to reality in Russia. It made the rise of Nazism in Germany possible. It butchered innocence and optimism along with millions of young men. Europe no longer had the self-confidence, or the money, to maintain colonial empires after the war, so most of mankind was swiftly cut adrift into the modern world without proper guidance in how to cope in it. It brought the US and Russia to the fore of world power. But the battle of attrition of that war wasn't properly concluded. The peace that was imposed was so mild, yet seemingly so harsh, that Germany was both motivated to, and able to attack again in 30 years, bringing on even greater human catastrophe, and dimming Europe's star, perhaps forever.

The day that ended that nightmare of a war has been commemorated solemnly ever since. When I was a child there were still many World War I veterans alive. But, as Tommy Makem and Liam Clancy sang, "The old men still answer the call/But year after year, the numbers get fewer/Someday no one will march there at all." Today the youngest veteran of World War I is in his late 90s. Very few people have contact with anyone who fought that grievous, bloody, pitiless war. Sadly, World War I has become a forgotten war. The subsequent history of mankind has made a mock of the claim that "The Great War" would end all wars.

On a personal note, my grandfather and his brother enlisted in the 1st Battalion, Connaught Rangers (formerly the 88th Regiment of Foot) in 1915. My grandfather was a gas casualty at Ypres, but survived the war. He died in 1936, 28 years before I was born.

At eleven minutes after the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, World War I ended. It was a war entered into by most of Europe with jubilation 4 years before. The astonishing slaughter of the trenches in pointless battles at Verdun, Ypres, the Somme, the Argonne, the Marne, and Gallipoli turned the jubilation into bleak despair as Europe's generals could think of nothing better than to have an entire generation slaughtered and maimed, while their governments ginned up what popular enthusiasm they could by proclaiming it a war to end all wars.

World War I ended Europe's dominance of the world. It's outcome abruptly ended the rule of the Romanovs, Habsburgs, and Hohenzollerns. It brought the menace of communism to reality in Russia. It made the rise of Nazism in Germany possible. It butchered innocence and optimism along with millions of young men. Europe no longer had the self-confidence, or the money, to maintain colonial empires after the war, so most of mankind was swiftly cut adrift into the modern world without proper guidance in how to cope in it. It brought the US and Russia to the fore of world power. But the battle of attrition of that war wasn't properly concluded. The peace that was imposed was so mild, yet seemingly so harsh, that Germany was both motivated to, and able to attack again in 30 years, bringing on even greater human catastrophe, and dimming Europe's star, perhaps forever.

The day that ended that nightmare of a war has been commemorated solemnly ever since. When I was a child there were still many World War I veterans alive. But, as Tommy Makem and Liam Clancy sang, "The old men still answer the call/But year after year, the numbers get fewer/Someday no one will march there at all." Today the youngest veteran of World War I is in his late 90s. Very few people have contact with anyone who fought that grievous, bloody, pitiless war. Sadly, World War I has become a forgotten war. The subsequent history of mankind has made a mock of the claim that "The Great War" would end all wars.

On a personal note, my grandfather and his brother enlisted in the 1st Battalion, Connaught Rangers (formerly the 88th Regiment of Foot) in 1915. My grandfather was a gas casualty at Ypres, but survived the war. He died in 1936, 28 years before I was born.

Abigail Adams

The second First Lady, and the first American woman to be the wife of one and mother of another president (a category she shares with only Barbara Bush), was born on this day in Weymouth, Massachusetts in 1744. But we just discussed her extensively on the anniversary of her death on October 28th.

The second First Lady, and the first American woman to be the wife of one and mother of another president (a category she shares with only Barbara Bush), was born on this day in Weymouth, Massachusetts in 1744. But we just discussed her extensively on the anniversary of her death on October 28th.

Saint Martin of Tours

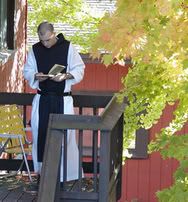

Today the Church celebrates Saint Martin of Tours, one of the most important saints in western Christendom. Martin was born in Pannonia around 325, and entered the Roman army's elite cavalry at an early age. Encountering a beggar while was stationed at Amiens, he divided his cloak with him. Shortly after age 20, he was baptized and left the army, becoming an exorcist under the direction of Saint Hilary of Poitiers.

He lived as a hermit on the island of Gallinaria, and returned to Gaul where he founded a monastery at Liguge, the first important monastery in the West. His monastery followed the Rule of Saint Basil. In 371, he was forcibly carried off to become bishop of Tours. He had hidden from the delegation from Tours, but his hiding place, it is said, was revealed by a goose, hence the custom of eating goose on Martinmas.

He ruled the see of Tours for 26 years. In that time, he made numerous conversions in Berry, Touraine, Anjou, Beauce, Dauphiny, Paris, Luxembourg, Trier, and Sennonais. Wherever he went, he cast down idols, built churches, and left priests and monks to carry out his work.

In 397, worn out, he lay dying at Candes. His followers begged him to live. He struggled to say, "If God finds that I can still be of use to His people, I do not at all refuse to work and to struggle longer." He died with his face turned to Heaven.

He became almost immediately, the most popular saint in Chistendom. In France alone, 4,000 churches are dedicated to him, and over 500 villages are named for him.

Martinmas in Europe corresponds to the traditional time for slaughtering animals not intended to be kept alive through the winter. It also signals the time that the new vintage of wine is ready for drinking. Fresh beef and Beaujolais Noveau have traditionally meant feasting in Europe. So Martinmas has traditionally been a jolly time, a last opportunity to enjoy God's bounty before the fast of Advent starts.

Today the Church celebrates Saint Martin of Tours, one of the most important saints in western Christendom. Martin was born in Pannonia around 325, and entered the Roman army's elite cavalry at an early age. Encountering a beggar while was stationed at Amiens, he divided his cloak with him. Shortly after age 20, he was baptized and left the army, becoming an exorcist under the direction of Saint Hilary of Poitiers.

He lived as a hermit on the island of Gallinaria, and returned to Gaul where he founded a monastery at Liguge, the first important monastery in the West. His monastery followed the Rule of Saint Basil. In 371, he was forcibly carried off to become bishop of Tours. He had hidden from the delegation from Tours, but his hiding place, it is said, was revealed by a goose, hence the custom of eating goose on Martinmas.

He ruled the see of Tours for 26 years. In that time, he made numerous conversions in Berry, Touraine, Anjou, Beauce, Dauphiny, Paris, Luxembourg, Trier, and Sennonais. Wherever he went, he cast down idols, built churches, and left priests and monks to carry out his work.

In 397, worn out, he lay dying at Candes. His followers begged him to live. He struggled to say, "If God finds that I can still be of use to His people, I do not at all refuse to work and to struggle longer." He died with his face turned to Heaven.

He became almost immediately, the most popular saint in Chistendom. In France alone, 4,000 churches are dedicated to him, and over 500 villages are named for him.

Martinmas in Europe corresponds to the traditional time for slaughtering animals not intended to be kept alive through the winter. It also signals the time that the new vintage of wine is ready for drinking. Fresh beef and Beaujolais Noveau have traditionally meant feasting in Europe. So Martinmas has traditionally been a jolly time, a last opportunity to enjoy God's bounty before the fast of Advent starts.

Monday, November 10, 2003

If Homosexual Sex Isn't Adultery, Is It A Violation of Vows?

The New Hampshire Supreme Court has come down with the most astonishing decision I have seen in some time. Lesbian sex does not constitute adultery.

The implications are pretty astounding. It means that, in New Hampshire law, it is perfectly OK to cheat on your spouse with another man or woman. No grounds for divorce except the ubiquitous "no-fault" (or maybe mental cruelty).

But if a married woman can have sex with another woman without committing adultery, would the law say that a priest having sex with a young boy did not violate his vow of chastity/celibacy? Are we back to the canard briefly raised by some early on in the pervert priest crisis that, sex with a young boy is not a violation of vows, because you can only violate your vows by having sex with a woman?

It is an absurd position, and one with no grounds in real life. The New Hampshire Supreme Court has done the state, and our entire society, a disservice here.

The New Hampshire Supreme Court has come down with the most astonishing decision I have seen in some time. Lesbian sex does not constitute adultery.

The implications are pretty astounding. It means that, in New Hampshire law, it is perfectly OK to cheat on your spouse with another man or woman. No grounds for divorce except the ubiquitous "no-fault" (or maybe mental cruelty).

But if a married woman can have sex with another woman without committing adultery, would the law say that a priest having sex with a young boy did not violate his vow of chastity/celibacy? Are we back to the canard briefly raised by some early on in the pervert priest crisis that, sex with a young boy is not a violation of vows, because you can only violate your vows by having sex with a woman?

It is an absurd position, and one with no grounds in real life. The New Hampshire Supreme Court has done the state, and our entire society, a disservice here.

The Headline Does Not Match the Story

According to the headline, and the invitation to outraged Catholics to call the rectory to complain, this priest incorporates Halloween themes in the Mass, saying Mass in a Dracula cape.

But the story makes it pretty clear, I think, that this is a special presentation, not a Mass. The priest explains things like demons turned into gargoyles by medieval church architects, and the religious significance of the season of the dead, and the jack-o-lantern. You could go on to list the purported effects of a Crucifix on vampires.

It does not sound like he is doing what the headline claims, which would be making a mockery of the Mass.

Just recognizing the Christian, in fact, Catholic aspects of Hallowmas is fine. It is, afterall, a Catholic holiday.

it seems to me that the publication is hankering for a fight with the modern world (or the world of the last hundred years). They might as well object to Christmas because we use holly and ivy, Yule logs and candles, and luck visits to celebrate it. Those are all carry-overs of pagan customs, adapted to the celebration of a Christian feast. You might also mention rabbits, eggs, and flowers at Easter.

Maintaining good Catholic practices and teachings is one thing. But trying to stamp out traditional seasonal customs that are associated with Christian feasts but are not themselves Christian in origin is a form of puritanism. It has little appeal. It is unneccessary. The Church has for two millenia avoided this sort of thing. Why raise it now?

According to the headline, and the invitation to outraged Catholics to call the rectory to complain, this priest incorporates Halloween themes in the Mass, saying Mass in a Dracula cape.

But the story makes it pretty clear, I think, that this is a special presentation, not a Mass. The priest explains things like demons turned into gargoyles by medieval church architects, and the religious significance of the season of the dead, and the jack-o-lantern. You could go on to list the purported effects of a Crucifix on vampires.

It does not sound like he is doing what the headline claims, which would be making a mockery of the Mass.

Just recognizing the Christian, in fact, Catholic aspects of Hallowmas is fine. It is, afterall, a Catholic holiday.

it seems to me that the publication is hankering for a fight with the modern world (or the world of the last hundred years). They might as well object to Christmas because we use holly and ivy, Yule logs and candles, and luck visits to celebrate it. Those are all carry-overs of pagan customs, adapted to the celebration of a Christian feast. You might also mention rabbits, eggs, and flowers at Easter.

Maintaining good Catholic practices and teachings is one thing. But trying to stamp out traditional seasonal customs that are associated with Christian feasts but are not themselves Christian in origin is a form of puritanism. It has little appeal. It is unneccessary. The Church has for two millenia avoided this sort of thing. Why raise it now?

Latin Or English ?

As I have said many times, I am not a determined partisan of the Latin Mass. I think it is a beautiful liturgy, dignified, and probably most importantly, sought out by people truly serious about tradition and the Faith. As long as it is said pursuant to the indults available through the line of authority that stretches back to the Holy Father, I have no problem with it.

Likewise, while my tastes run towards the most conservative means of celebrating the 1970 Novus Ordo Mass, I recognize the legitimacy of that rite (even when I don't like what it looks like), and in fact attend it almost exclusively.

I know that Tridentine Catholic purists hate the idea of a "hybrid Mass" one that combines a good part of both rites. And Novus Ordo enthusiasts dislike the idea of retaining any Latin or Greek. But in my humble opinion, if I were sent back in time to 1970, and had been given dictatorial power over the reform of the liturgy (what we in high school debate used to be called "affirmative fiat": the power to wish that any reform you wanted was made law to the degree of your slightest whim) what would have emerged would have been, in fact, a hybrid.

I've seen the Latin Mass both high and low (you might remember the particular tape I own: it was advertised in National Review in the late 1980s-early 1990s and was taped in England sometime between 1984-86). A couple of things struck me that I did not like.

It was hard to follow. Not in the sense that I could not follow the Latin. There was a translation included in a booklet with the cassette. I had five years of Latin and, although the corrupted Latin prounciation of the Church is off-putting to someone who was trained in what scholars believe Latin actually sounded like at the time of the Lord (and Cicero- Ceeckero-and Vergil,-Wergill), I could look past that. Not because the priest was not facing the congregation. But because he mumbled and sped through so much of the rite, or there was music (wonderfully beautiful music, I might add) going on over him. And he did not apparently have a cordless mike clipped on. So you could only really tell where he was, especially in the low Mass, by the bells and his movements and actions (which of course you can't see fromt he back of the Church).

The Tridentine rite is too long. If the priest did not speed through it mumbling sotto voce so that only he understands what is being said, a low Mass would take at least an hour and a half. A routine High Mass without any special seasonal embellishments might take three hours.

That said, let's look at what I dislike about the Novus Ordo. In this case, it is more what individual parishes and priests do to the Mass, than the Mass itself that is annoying. The one peeve that is systemic is the use of a terrible, unpoetic translation. Could we not have retained the translation in use before Vatican II, or even, in a spirit of ecumenism, have adopted elements of the wonderful King James translation that bear no Protestant theological baggage of any significance Frankly, when I pray the 22/23rd Psalm, and read the Christmas story from St. Luke, I prefer to not use the flat Catholic translation, but the traditional King James that is familiar to every educated English-speaking person.

Mostly, my objections come from experimentation, improvising, musical innovation, adapting Masses for particular groups, adoption of too much Protestant music, too much music that is "me-centered", changes in the manner of distributing the Sacrament, and changing how and when the congregation kneels, sits and stands. Toss in changes that have taken place outside the liturgy in how the congregation dresses, behaves, disciplines their children (or doesn't), and in how modern chruches are built and decorated, and in what priests preach about, and you have a pretty complete catalogue of my peeves about the new Mass.

I have experienced wonderful Novus Ordo Masses. They took place in older, traditionally designed and decorated churches. The priest saying the Mass gave a good no-nonsense sermon. There was no innovation, no kids standing up at the front, no parading in the Lectionary as if it were the Ark of the Covenant, no Communion under both Species except on Corpus Christi and Holy Thursday, and maybe the feast of the Church's patron, no grip 'n grin, no PCing the words of the Mass itself or the hymns, no undisciplined children running amok. The music was traditionally Catholic.

So what would I have done differently in 1970? As I said, the Mass would have been a hybrid, a reformed Mass that would still be very recognizable to someone living at the turn of the century. Many of the common portions of the Mass would have stayed in Latin, but they would have been simplified. Responses, too, would also be in Latin. It doesn't take much to pray the Pater Noster in Latin, to say nothing of "Et cum spiritu tuo." The Creed and Gloria would have to be said in English because of their length. But the Sanctus and Agnus Dei would have stayed in Latin, and the Kyrie in Greek. I like the innovation of the two readings, instead of the one Epistle. But they would have been in the vernacular (as would the prayers particular for that day (though not the seasonal sequences), with only the short common responses in Latin.

The priest would probably have remained facing the altar (and tabernacle as the centrality of the Real Presence is the whole point of the Mass). But he would have had a mike clipped on, and the way he said the Mass would have changed. No more mumbling and speed-reading through it. The words would be said clearly and distinctly, just as priests do with the vernacular. People would be able to hear every word, and follow along in the line-by-line translations available to each and every person in the congegation.

Given that the priest was now speaking slowly and distinctly, the Mass would have to be trimmed. The wonderful, but unneccessary, Last Gospel would have disappeared. The rite would generally have been simplified.

Liturgical music would have changed in two respects. No longer would the priest be drowned out by it. Once the priest got to, say, the Agnus Dei, the choir or schola could start it. When the priest finished, he would not continue on, but stop, and wait for the music to stop before going on. On the other hand, the suppression of traditional Catholic hymns, and the gender-bending PCing of hymns both traditional and modern, would not have taken place. A handful of decent Protestant hymns would probably have been approved. But you certainly would not hear them every week.

Would it work that way? I think so. And I think the result would not have been as off-putting to traditionalists, or acted as a sample of red meat for the rabid reformers. Would that it had happened. There would have been, I think, much less turmoil, and much less debasement and experimentation.

As I have said many times, I am not a determined partisan of the Latin Mass. I think it is a beautiful liturgy, dignified, and probably most importantly, sought out by people truly serious about tradition and the Faith. As long as it is said pursuant to the indults available through the line of authority that stretches back to the Holy Father, I have no problem with it.

Likewise, while my tastes run towards the most conservative means of celebrating the 1970 Novus Ordo Mass, I recognize the legitimacy of that rite (even when I don't like what it looks like), and in fact attend it almost exclusively.

I know that Tridentine Catholic purists hate the idea of a "hybrid Mass" one that combines a good part of both rites. And Novus Ordo enthusiasts dislike the idea of retaining any Latin or Greek. But in my humble opinion, if I were sent back in time to 1970, and had been given dictatorial power over the reform of the liturgy (what we in high school debate used to be called "affirmative fiat": the power to wish that any reform you wanted was made law to the degree of your slightest whim) what would have emerged would have been, in fact, a hybrid.

I've seen the Latin Mass both high and low (you might remember the particular tape I own: it was advertised in National Review in the late 1980s-early 1990s and was taped in England sometime between 1984-86). A couple of things struck me that I did not like.

It was hard to follow. Not in the sense that I could not follow the Latin. There was a translation included in a booklet with the cassette. I had five years of Latin and, although the corrupted Latin prounciation of the Church is off-putting to someone who was trained in what scholars believe Latin actually sounded like at the time of the Lord (and Cicero- Ceeckero-and Vergil,-Wergill), I could look past that. Not because the priest was not facing the congregation. But because he mumbled and sped through so much of the rite, or there was music (wonderfully beautiful music, I might add) going on over him. And he did not apparently have a cordless mike clipped on. So you could only really tell where he was, especially in the low Mass, by the bells and his movements and actions (which of course you can't see fromt he back of the Church).

The Tridentine rite is too long. If the priest did not speed through it mumbling sotto voce so that only he understands what is being said, a low Mass would take at least an hour and a half. A routine High Mass without any special seasonal embellishments might take three hours.

That said, let's look at what I dislike about the Novus Ordo. In this case, it is more what individual parishes and priests do to the Mass, than the Mass itself that is annoying. The one peeve that is systemic is the use of a terrible, unpoetic translation. Could we not have retained the translation in use before Vatican II, or even, in a spirit of ecumenism, have adopted elements of the wonderful King James translation that bear no Protestant theological baggage of any significance Frankly, when I pray the 22/23rd Psalm, and read the Christmas story from St. Luke, I prefer to not use the flat Catholic translation, but the traditional King James that is familiar to every educated English-speaking person.

Mostly, my objections come from experimentation, improvising, musical innovation, adapting Masses for particular groups, adoption of too much Protestant music, too much music that is "me-centered", changes in the manner of distributing the Sacrament, and changing how and when the congregation kneels, sits and stands. Toss in changes that have taken place outside the liturgy in how the congregation dresses, behaves, disciplines their children (or doesn't), and in how modern chruches are built and decorated, and in what priests preach about, and you have a pretty complete catalogue of my peeves about the new Mass.

I have experienced wonderful Novus Ordo Masses. They took place in older, traditionally designed and decorated churches. The priest saying the Mass gave a good no-nonsense sermon. There was no innovation, no kids standing up at the front, no parading in the Lectionary as if it were the Ark of the Covenant, no Communion under both Species except on Corpus Christi and Holy Thursday, and maybe the feast of the Church's patron, no grip 'n grin, no PCing the words of the Mass itself or the hymns, no undisciplined children running amok. The music was traditionally Catholic.

So what would I have done differently in 1970? As I said, the Mass would have been a hybrid, a reformed Mass that would still be very recognizable to someone living at the turn of the century. Many of the common portions of the Mass would have stayed in Latin, but they would have been simplified. Responses, too, would also be in Latin. It doesn't take much to pray the Pater Noster in Latin, to say nothing of "Et cum spiritu tuo." The Creed and Gloria would have to be said in English because of their length. But the Sanctus and Agnus Dei would have stayed in Latin, and the Kyrie in Greek. I like the innovation of the two readings, instead of the one Epistle. But they would have been in the vernacular (as would the prayers particular for that day (though not the seasonal sequences), with only the short common responses in Latin.

The priest would probably have remained facing the altar (and tabernacle as the centrality of the Real Presence is the whole point of the Mass). But he would have had a mike clipped on, and the way he said the Mass would have changed. No more mumbling and speed-reading through it. The words would be said clearly and distinctly, just as priests do with the vernacular. People would be able to hear every word, and follow along in the line-by-line translations available to each and every person in the congegation.

Given that the priest was now speaking slowly and distinctly, the Mass would have to be trimmed. The wonderful, but unneccessary, Last Gospel would have disappeared. The rite would generally have been simplified.

Liturgical music would have changed in two respects. No longer would the priest be drowned out by it. Once the priest got to, say, the Agnus Dei, the choir or schola could start it. When the priest finished, he would not continue on, but stop, and wait for the music to stop before going on. On the other hand, the suppression of traditional Catholic hymns, and the gender-bending PCing of hymns both traditional and modern, would not have taken place. A handful of decent Protestant hymns would probably have been approved. But you certainly would not hear them every week.

Would it work that way? I think so. And I think the result would not have been as off-putting to traditionalists, or acted as a sample of red meat for the rabid reformers. Would that it had happened. There would have been, I think, much less turmoil, and much less debasement and experimentation.

Sunday, November 09, 2003

Hosea

A hymn that I was unfamiliar with, produced by a Benedictine, Dom Gregory Norbert, in the 1970s was sung at Mass today. Once I saw the date, I was ready to tune it out. But for some reason I listened. It was beautifully, slowly, gracefully sung by a female soloist accompanying herself on the organ. Her rendition, the wonderful setting, and the lyrics brought tears to my eyes. It is not as zippy as the lyrics look.

Come back to me with all your heart,

don’t let fear keep us apart.

Trees do bend, tho’ straight and tall;

so must we to others’ call.

LONG HAVE I WAITED FOR YOUR COMING

HOME TO ME AND LIVING DEEPLY OUR NEW LIFE.

The wilderness will lead you

to your heart where I will speak.

Integrity and justice

with tenderness you shall know.