Saturday, November 26, 2011

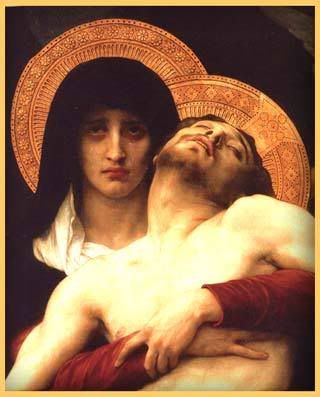

Our Blessed Lady's Saturday

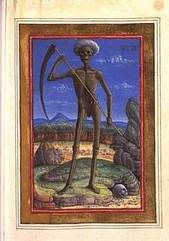

LANGUENTIBUS IN PURGATORIO

Those languishing in Purgatory,

who are purified in a fire beyond measure,

and are tormented in grevious suffering,

may thy compassion relieve: O Mary!

Thou art the clear fountain that washes sins away,

thou assisteth all and reject none;

extend thine hand to the dead,

who languish under continual pains: O Mary!

The dead piously sigh unto thee,

longing to be delivered from their pains,

and to be present in thy sight,

and fully to enjoy eternal joys: O Mary!

Hasten, O Mother, to those lamenting,

show thine heart of mercy;

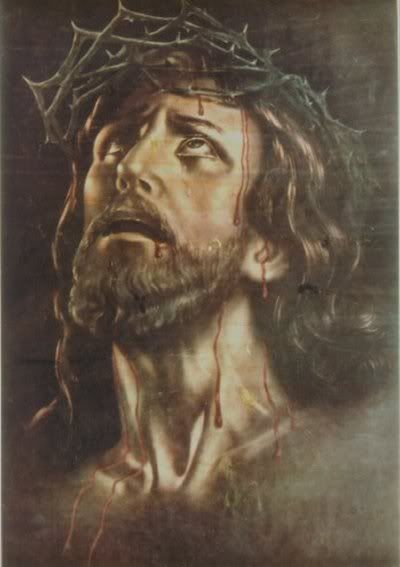

obtain that Jesus by His wounds

may vouchsafe to heal them: O Mary!

Thou the true hope of those crying out to thee;

the multitude of members cry out to thee

for their brethren, that thou may appease thy Son,

and He may give them the heavenly reward: O Mary!

Impart those tears that thou consider good things,

which we pour out at the feet of the Judge;

may they now extinguish the might of the avenging fire,

that (the dead) may be joined to the angelic choirs: O Mary!

And when the just examination shall take place,

at the awesome judgment of God,

entreat thy Son judging,

that our portion may be with the saints: O Mary!

Amen.

Labels: Our Blessed Lady

Friday, November 25, 2011

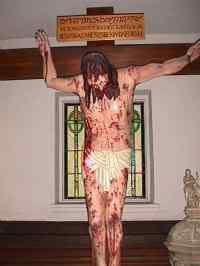

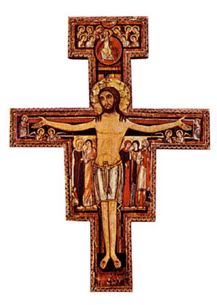

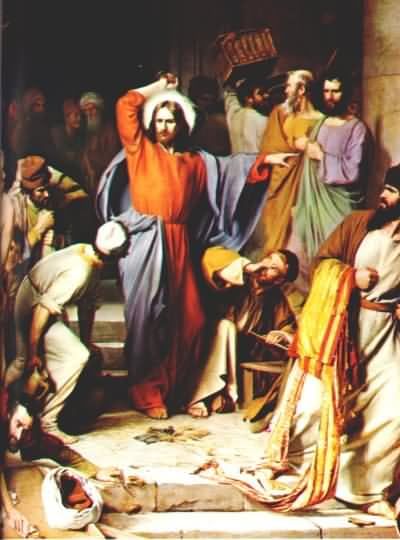

Friday At the Foot Of the Cross

LORD God almighty, I beseech Thee,

by the precious blood

which Thy Divine Son shed on this day,

upon the wood of the Cross,

from His most sacred hands and feet,

deliver the souls in purgatory,

and especially that soul

for which I am most bound to pray;

that the blame rest not with me

that Thou bringest it not forth

to praise Thee in Thy glory

and to bless Thee forever.

Amen.

Labels: Friday At the Foot Of the Cross

Thursday, November 24, 2011

My Thanksgiving Wish

I would like to take this opportunity to wish all of my readers and loved ones a happy and joyous Thanksgiving. Even in tough times (and we are not quite out of the woods yet) and in war, we have much to be thankful for in this wonderful country.

May God, in His mercy, through the graces imparted by Our Blessed Lady, grant us reconciliation, peace, harmony, and renewed joy. May He bind up old wounds, help us grow and mature, and always live in the light of the Gospel and in His grace.

God bless you all.

May God, in His mercy, through the graces imparted by Our Blessed Lady, grant us reconciliation, peace, harmony, and renewed joy. May He bind up old wounds, help us grow and mature, and always live in the light of the Gospel and in His grace.

God bless you all.

Labels: Thanksgiving

My Thanksgiving Prayer

On this Thanksgivng Day, Lord, we Thy people count our blessings, which Thou hast given us. With joyful gratitutude, we raise our voices in praise of the Author of Creation.

We thank Thee for the gifts of life, free will, and good health of both body and mind.

We thank Thee for the bountiful food we eat, the warm clothes we wear, the shelter of our homes, the love and comfort of our families.

We thank Thee for gainful and challenging employment.

We thank thee for a free country, made prosperous by Thy grace and the effective exercise of our free will.

We thank Thee for the rights to earn our bread, speak our minds, elect our leaders, choose our friends, protect our families, and worship Thee.

We thank Thee for those who make our freedom possible: EMTs, doctors and nurses, firemen, policemen, soldiers, airmen, sailors, marines, Coast Guardsmen, agents, analysts, and national leaders.

We thank Thee for the sacrifice of so many brave young men who have given the last full measure of devotion, and for all who have served, so that we may live free in this land Thou hast provided for us.

We thank Thee for the gift of Faith which helps us to understand that we shall transcend all difficulties through Thy grace.

We thank thee for Thy Church here on earth, divided as it is, troubled by sin, beset by Satan, yet ultimately triumphant.

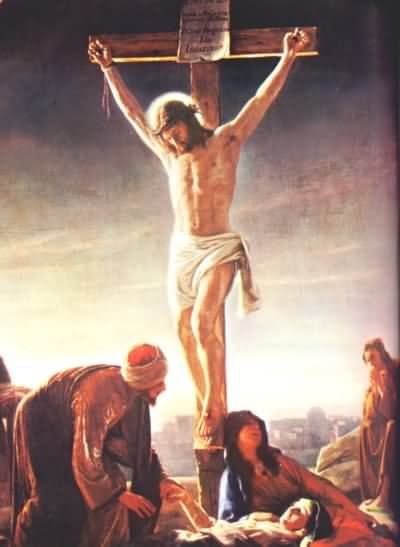

Most of all, Lord, we thank Thee for Thy Sacrifice on Calvary, which opened the gates of Heaven to us, giving us the promise of eternal life.

We adore and thank Christ, Oh Christ, and we praise Thee, because by Thy holy cross, Thou hast redeemed the world.

We thank Thee for the gifts of life, free will, and good health of both body and mind.

We thank Thee for the bountiful food we eat, the warm clothes we wear, the shelter of our homes, the love and comfort of our families.

We thank Thee for gainful and challenging employment.

We thank thee for a free country, made prosperous by Thy grace and the effective exercise of our free will.

We thank Thee for the rights to earn our bread, speak our minds, elect our leaders, choose our friends, protect our families, and worship Thee.

We thank Thee for those who make our freedom possible: EMTs, doctors and nurses, firemen, policemen, soldiers, airmen, sailors, marines, Coast Guardsmen, agents, analysts, and national leaders.

We thank Thee for the sacrifice of so many brave young men who have given the last full measure of devotion, and for all who have served, so that we may live free in this land Thou hast provided for us.

We thank Thee for the gift of Faith which helps us to understand that we shall transcend all difficulties through Thy grace.

We thank thee for Thy Church here on earth, divided as it is, troubled by sin, beset by Satan, yet ultimately triumphant.

Most of all, Lord, we thank Thee for Thy Sacrifice on Calvary, which opened the gates of Heaven to us, giving us the promise of eternal life.

We adore and thank Christ, Oh Christ, and we praise Thee, because by Thy holy cross, Thou hast redeemed the world.

Labels: Thanksgiving

Psalm 66/67

A Psalm of Thanksgiving

May God have mercy on us, and bless us: may He cause the light of His countenance to shine upon us, and may He have mercy on us.

That we may know Thy way upon earth: Thy salvation in all nations.

Let people confess to Thee, O God: let all people give praise to Thee.

Let the nations be glad and rejoice: for Thou judgest the people with justice, and directest the nations upon earth.

Let the people, O God, confess to Thee: let all the people give praise to Thee:

The earth hath yielded her fruit. May God, our God bless us,

May God bless us: and all the ends of the earth fear Him.

May God have mercy on us, and bless us: may He cause the light of His countenance to shine upon us, and may He have mercy on us.

That we may know Thy way upon earth: Thy salvation in all nations.

Let people confess to Thee, O God: let all people give praise to Thee.

Let the nations be glad and rejoice: for Thou judgest the people with justice, and directest the nations upon earth.

Let the people, O God, confess to Thee: let all the people give praise to Thee:

The earth hath yielded her fruit. May God, our God bless us,

May God bless us: and all the ends of the earth fear Him.

Labels: Thanksgiving

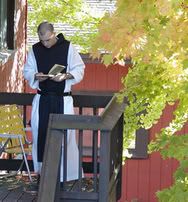

Saint John Of the Cross

The Catholic Encyclopedia on this great Carmelite reformer and mystic.

Here is the Wiki.

Saint John of the Cross, please pray for us!

Labels: Our Saintly Brethern

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

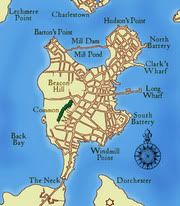

Two Primary Accounts Of the First Thanksgiving

The first is from Governor William Bradford's history of the Plymouth Colony. The second is from Mort's Relation.

"William Bradford. "Bradford's History Of Plimoth Plantation." Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Co., State Printers... 1898. p. 127

E.W., Plymouth, in New England, this 11th of December, 1621. in A RELATION OR Journal of the beginning and proceedings of the English Plantation settled at Plimoth in NEW ENGLAND, by certaine English Aduenturers both Merchants and others. LONDON,Printed for John Bellamie,..1622. pp. 60-61.

"They begane now to gather in ye small harvest they had, and to fitte up their houses and dwellings against winter, being well recovered in health & strenght, and had all things in good plenty; for some were thus imployed in affairs abroad, others were excersised in fishing, aboute codd, & bass, & other fish, of which yey tooke good store, of which every family had their portion. All ye somer ther was no wante. And now begane to come in store of foule, as winter aproached, of which this place did abound when they came first (but afterward decreased by degree). And besids water foule, ther was great store of wild Turkies, of which they took many, besids venison, &c. Besids they had aboute a peck a meale a weeke to a person, or now since harvest, Indean corne to yt proportion. Which made many afterwards write so largly of their plenty hear to their friends in England, which were not fained, but true reports.

"William Bradford. "Bradford's History Of Plimoth Plantation." Boston: Wright & Potter Printing Co., State Printers... 1898. p. 127

"Our Corne did proue well, & God be praysed, we had a good increase of Indian Corne, and our Barly indifferent good, but our Pease not worth the gathering, for we feared they were too late sowne, they came vp very well, and blossomed, but the Sunne parched them in the blossome; our harvest being gotten in, our Governour sent foure men on fowling, that so we might after a more speciall manner reioyce together, after we had gathered the fruit of our labors; they foure in one day killed as much fowle, as with a little helpe beside, served the Company almost a weeke, at which time amongst other Recreations, we exercised our Armes, many of the Indians coming amongst vs, and among the rest their greatest King Massasoyt, with some nintie men, whom for three dayes we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed fiue Deere, which they brought to the Plantation and bestowed upon our Governour, and upon the Captaine, and others. And although it be not alwayes so plentifull, as it was at this time with vs, yet by the goodneses of God, we are so farre from want, that we often wish you partakers of our plenty."

E.W., Plymouth, in New England, this 11th of December, 1621. in A RELATION OR Journal of the beginning and proceedings of the English Plantation settled at Plimoth in NEW ENGLAND, by certaine English Aduenturers both Merchants and others. LONDON,Printed for John Bellamie,..1622. pp. 60-61.

Labels: Thanksgiving

Mid-Week Mix Thanksgiving Special Edition

A Thanksgiving theme for this week's edition.

Over the River and Through the Woods

We Gather Together

Harvest Home

Come Ye Thankful People, Come

All Things Bright And Beautiful

Mel Torme, Sleigh Ride

Perry Como, There's No Place Like Home For the Holidays

Bing Crosby, Faith Of Our Fathers

Over the River and Through the Woods

We Gather Together

Harvest Home

Come Ye Thankful People, Come

All Things Bright And Beautiful

Mel Torme, Sleigh Ride

Perry Como, There's No Place Like Home For the Holidays

Bing Crosby, Faith Of Our Fathers

Labels: Pleasing Tunes, Thanksgiving

Harvest Home

The Horkey by Robert Bloomfield

The first Thanksgiving was really just an English Harvest Home celebration, and probably occurred in either late September, or October, when the harvest is all in here in Massachusetts.

Labels: Thanksgiving

The Turkey Or the Eagle?

Benjamin Franklin caused a minor commotion in objecting to the adoption of the bald eagle as the symbol of the United States. He preferred our favorite Thanksgiving fare, the turkey.

Others, including John Adams, objected that the turkey was notoriously stupid as well.

But the country has settled into a happy compromise.

"May one give us peace in all our states,

The other a piece for all our plates."

"For my part, I wish the bald eagle had not been chosen representative of our country; he is a bird of bad moral character....For in truth the turkey is in comparison a much more respectable bird withal, a true original native of America. Eagles have been found in all countries, but the turkey is peculiar to ours...he is besides (though a little vain and silly, it is true), a bird of courage who would not hesitate to attack a grenadier of the British Guard who should presume to invade his farmyard with a red coat on."

Others, including John Adams, objected that the turkey was notoriously stupid as well.

But the country has settled into a happy compromise.

"May one give us peace in all our states,

The other a piece for all our plates."

Labels: Thanksgiving

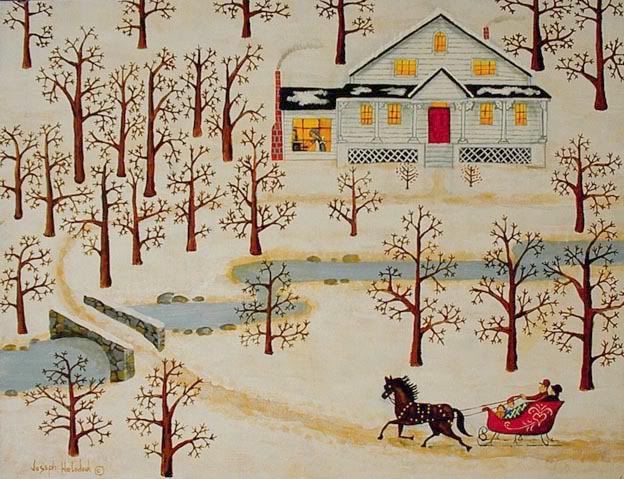

For the Busiest Travel Day Of the Year

Over the river and through the woods

To Grandfather's house we go.

The horse knows the way

To carry the sleigh

Through white and drifted snow.

Over the river and through the wood --

Oh, how the wind does blow!It stings the toes

And bites the nose,

As over the ground we go.

Over the river and through the woods

To have a first-rate play.

Hear the bells ring,Ting-a-ling-ling!

Hurrah forThanksgiving Day!

Over the river and through the wood,

Trot fast, my dapple gray!

Spring over the groundLike a hunting hound,

For this is Thanksgiving Day.

Over the river and through the woods,

And straight through the barnyard gate.

We seem to go

Extremely slow --

It is so hard to wait!

Over the river and through the wood --

Now Grandmother's cap I spy!

Hurrah for fun!Is the pudding done?

Hurrah for the pumpkin pie!

Labels: Thanksgiving

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

Massachusetts And Pies

Pies are not only the primary dessert for Thanksgiving, but are very popular year-round throughout New England. Unlike the author of the following doggerel, I love pies. Bring them on. The more, the merrier.

And this little ditty was written at least a century before Boston Cream Pie came into prominence.

Mmmmmmm. Mince pie. Yummy!

In Massachusetts, sad to say

From Gloucester down to Cape Cod Bay

They feed you 'til you want to die

On mincemeat and pumpkin pie.

Until at last it makes you cry,

"What else is there that I can try?'

They look at you in some surprise

And feed you apple and custard pies.

And this little ditty was written at least a century before Boston Cream Pie came into prominence.

Mmmmmmm. Mince pie. Yummy!

Labels: Thanksgiving

The Pumpkin

by John Greenleaf Whittier

Oh, greenly and fair in the lands of the sun,

The vines of the gourd and the rich melon run,

And the rock and the tree and the cottage enfold,

With broad leaves all greenness and blossoms all gold,

Like that which o'er Nineveh's prophet once grew,

While he waited to know that his warning was true,

And longed for the storm-cloud, and listened in vain

For the rush of the whirlwind and red fire-rain.

On the banks of the Xenil the dark Spanish maiden

Comes up with the fruit of the tangled vine laden;

And the Creole of Cuba laughs out to behold

Through orange-leaves shining the broad spheres of gold;

Yet with dearer delight from his home in the North,

On the fields of his harvest the Yankee looks forth,

Where crook-necks are coiling and yellow fruit shines,

And the sun of September melts down on his vines.

Ah! on Thanksgiving day, when from East and from West,

From North and from South come the pilgrim and guest,

When the gray-haired New Englander sees round his board

The old broken links of affection restored,

When the care-wearied man seeks his mother once more,

And the worn matron smiles where the girl smiled before,

What moistens the lip and what brightens the eye?

What calls back the past, like the rich Pumpkin pie?

Oh, fruit loved of boyhood! the old days recalling,

When wood-grapes were purpling and brown nuts were falling!

When wild, ugly faces we carved in its skin,

Glaring out through the dark with a candle within!

When we laughed round the corn-heap, with hearts all in tune,

Our chair a broad pumpkin,--our lantern the moon,

Telling tales of the fairy who travelled like steam,

In a pumpkin-shell coach, with two rats for her team!

Then thanks for thy present! none sweeter or better

E'er smoked from an oven or circled a platter!

Fairer hands never wrought at a pastry more fine,

Brighter eyes never watched o'er its baking, than thine!

And the prayer, which my mouth is too full to express,

Swells my heart that thy shadow may never be less,

That the days of thy lot may be lengthened below,

And the fame of thy worth like a pumpkin-vine grow,

And thy life be as sweet, and its last sunset sky

Golden-tinted and fair as thy own pumpkin pie!

Oh, greenly and fair in the lands of the sun,

The vines of the gourd and the rich melon run,

And the rock and the tree and the cottage enfold,

With broad leaves all greenness and blossoms all gold,

Like that which o'er Nineveh's prophet once grew,

While he waited to know that his warning was true,

And longed for the storm-cloud, and listened in vain

For the rush of the whirlwind and red fire-rain.

On the banks of the Xenil the dark Spanish maiden

Comes up with the fruit of the tangled vine laden;

And the Creole of Cuba laughs out to behold

Through orange-leaves shining the broad spheres of gold;

Yet with dearer delight from his home in the North,

On the fields of his harvest the Yankee looks forth,

Where crook-necks are coiling and yellow fruit shines,

And the sun of September melts down on his vines.

Ah! on Thanksgiving day, when from East and from West,

From North and from South come the pilgrim and guest,

When the gray-haired New Englander sees round his board

The old broken links of affection restored,

When the care-wearied man seeks his mother once more,

And the worn matron smiles where the girl smiled before,

What moistens the lip and what brightens the eye?

What calls back the past, like the rich Pumpkin pie?

Oh, fruit loved of boyhood! the old days recalling,

When wood-grapes were purpling and brown nuts were falling!

When wild, ugly faces we carved in its skin,

Glaring out through the dark with a candle within!

When we laughed round the corn-heap, with hearts all in tune,

Our chair a broad pumpkin,--our lantern the moon,

Telling tales of the fairy who travelled like steam,

In a pumpkin-shell coach, with two rats for her team!

Then thanks for thy present! none sweeter or better

E'er smoked from an oven or circled a platter!

Fairer hands never wrought at a pastry more fine,

Brighter eyes never watched o'er its baking, than thine!

And the prayer, which my mouth is too full to express,

Swells my heart that thy shadow may never be less,

That the days of thy lot may be lengthened below,

And the fame of thy worth like a pumpkin-vine grow,

And thy life be as sweet, and its last sunset sky

Golden-tinted and fair as thy own pumpkin pie!

Labels: Thanksgiving

Saint Cecilia

Raphael, 1514, Bologna

Song For Saint Cecilia's Day

by John Dryden

From harmony, from heavenly harmony

This universal frame began:

When Nature underneath a heap

Of jarring atoms lay,

And could not heave her head,

The tuneful voice was heard from high,

"Arise, ye more than dead!"

Then cold and hot, and moist and dry,

In order to their stations leap,

And Music's power obey.

From harmony, from heavenly harmony

This universal frame began:

From harmony to harmony

Through all the compass of the notes it ran,

The diapason closing full in Man.

What passion cannot Music raise and quell?

When Jubal struck the chorded shell

His listening brethren stood around,

And, wondering, on their faces fell

To worship that celestial sound.

Less than a god they thought there could not dwell

Within the hollow of that shell

That spoke so sweetly and so well.

What passion cannot Music raise and quell?

The trumpet's loud clangour

Excites us to arms,

With shrill notes of anger

And mortal alarms.

The double double double beat

Of the thundering drum

Cries "Hark! the foes come;

Charge, charge, 'tis too late to retreat!"

The soft complaining flute

In dying notes discovers

The woes of hopeless lovers,

Whose dirge is whispered by the warbling lute.

Sharp violins proclaim

Their jealous pangs and desperation,

Fury, frantic indignation,

Depth of pains, and height of passion

For the fair disdainful dame.

But oh! what art can teach,

What human voice can reach

The sacred organ's praise?

Notes inspiring holy love,

Notes that wing their heavenly ways

To mend the choirs above.

Orpheus could lead the savage race,

And trees uprooted left their place

Sequacious of the lyre:

But bright Cecilia raised the wonder higher:

When to her Organ vocal breath was given

An Angel heard, and straight appeared -

Mistaking Earth for Heaven.

The Golden Legend on Saint Cecilia

Catholic On-Line's biography

Labels: Our Saintly Brethern

Monday, November 21, 2011

The Landing Of the Pilgrim Fathers

By Felicia Hemans

The breaking waves dash'd high

On a stern and rock-bound coast,

And the woods against a stormy sky

Their giant branches toss'd;

And the heavy night hung dark,

The hills and waters o'er,

When a band of exiles moor'd their bark

On the wild New-England shore.

Not as the conqueror comes,

They, the true-hearted came;

Not with the roll of the stirring drums,

And the trumpet that sings of fame:

Not as the flying come,

In silence and in fear;–

They shook the depths of the desert gloom

With their hymns of lofty cheer.

Amidst the storm they sang,

And the stars heard and the sea!

And the sounding aisles of the dim woods rang

To the anthem of the free.

The ocean-eagle soar'd

From his nest by the white wave's foam;

And the rocking pines of the forest roar'd–

This was their welcome home!

There were men with hoary hair,

Amidst that pilgrim band;–

Why had they come to wither there,

Away from their childhood's land?

There was woman's fearless eye,

Lit by her deep love's truth;

There was manhood's brow serenely high,

And the fiery heart of youth.

What sought they thus afar?

Bright jewels of the mine?

The wealth of seas, the spoils of war?–

They sought a faith's pure shrine!

Ay, call it holy ground,

The soil where first they trod!

They have left unstain'd what there they found–

Freedom to worship God.

The breaking waves dash'd high

On a stern and rock-bound coast,

And the woods against a stormy sky

Their giant branches toss'd;

And the heavy night hung dark,

The hills and waters o'er,

When a band of exiles moor'd their bark

On the wild New-England shore.

Not as the conqueror comes,

They, the true-hearted came;

Not with the roll of the stirring drums,

And the trumpet that sings of fame:

Not as the flying come,

In silence and in fear;–

They shook the depths of the desert gloom

With their hymns of lofty cheer.

Amidst the storm they sang,

And the stars heard and the sea!

And the sounding aisles of the dim woods rang

To the anthem of the free.

The ocean-eagle soar'd

From his nest by the white wave's foam;

And the rocking pines of the forest roar'd–

This was their welcome home!

There were men with hoary hair,

Amidst that pilgrim band;–

Why had they come to wither there,

Away from their childhood's land?

There was woman's fearless eye,

Lit by her deep love's truth;

There was manhood's brow serenely high,

And the fiery heart of youth.

What sought they thus afar?

Bright jewels of the mine?

The wealth of seas, the spoils of war?–

They sought a faith's pure shrine!

Ay, call it holy ground,

The soil where first they trod!

They have left unstain'd what there they found–

Freedom to worship God.

Labels: Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving In Revolutionary Massachusetts

The persistence of American Thanksgiving customs is impressive. While cranberry sauce and pumpkin pie may not have been on the menu at Plymouth in 1621, when venison and an unspecified "fowle"; graced the communal table, Americans have celebrated their unique holiday for giving thanks to God in ways that are highly recognizable from generation to generation, from century to century.

An excellent illustration of this is the Thanksgiving dinner described in her diary by Juliana Smith, the daughter of Massachusetts minister Reverend Smith in 1779. It is published nearly in full in We Gather Together, by Ralph and Adelin Linton, and published by Henry Schuman of New York in 1949 at pages 73-77.

This little-studied diary entry shows that the pattern for the American Thanksgiving celebration that people in the early 21st century continue to observe was in place even at the time of the nation's founding.

The dinner took place in the third year of the Revolutionary War, but reflects little wartime privation. Indeed for a country engaged in a great conflict to establish its independence, one is struck by the normality of the celebration. There is a prayer for absent friends, but one doubts that this prosperous family has supplied much in the way of cannon fodder for Washington's army. One son of military age is instead at college.

The Smith clan was a fairly prosperous one, but not great merchants. One of Juliana's uncles was a doctor, another an apparently prosperous farmer. Her father was the local Congregationalist minister.

Given the family's level of prosperity, it would be reasonable to question the typicality of their Thanksgiving feast. One must ask how representative their celebration is of their region and time. The participants in the Thanksgiving ritual we will closely observe all seem to be familiar with their expected roles, even when they do not come from the same household or class. So we can at least say that this mode of celebration was familiar to these people. But larger characterizations regarding typicality would require evidence outside the diary.

Such evidence does exist. It corroborates the contention that the Thanksgiving gathering described by Juliana Smith was indeed typical in its broad outlines, though perhaps more elaborate than most.

Miss Smith begins her description with some facets of the celebration that will be familiar to the modern householder. "This year, it was Uncle Simeon's turn to have the dinner at his house". So this family group, which by modern standards is rather large, is in the habit of rotating the responsibility for hosting the annual feast. This is a reasonable arrangement given the size and composition of the family group.

The titular heads of the family are the two grandmothers. Their children and their spouses, and their childrens' children form the core of the family group. In addition to them are neighbors, orphans, and stranded students, old people with no place else to celebrate the day, and servants.

Given such a large group, and the prosperity of at least two branches of the family, it would be entirely reasonable to share the responsibility for hosting this ritual gathering, not putting too much of the burden on any one branch year after year.

This custom speaks to the absence of any controlling pater familias, a Squire Bracebridge, if you like, who would not hear of Thanksgiving being celebrated anywhere but in the ancestral seat which he occupies. One wonders if this would be the case if one of Juliana Smith's grandfathers were still alive.

"All the baking of pies and cakes was done at our house & we had the big oven heated & filled twice each day for three days before it was all done". Yes, this is very familiar to moderns hosting a family gathering for Thanksgiving.

Food preparation is time-consuming. Then, without food processors, canned pumpkin, standardized measurements, a hundred utensils and conveniences, or pretty much unfailingly accurate and reliable ovens, it was more so. Three days seems reasonable for making all the pies for such a large gathering. Even today, with all the conveniences in the kitchen, a large meal like this needs to be started days in advance. The difference is in cold storage. There was no refrigeration per se, but the New England weather in late November was often chilly enough to make the cold storage of a farmhouse adequate to the task.

Also note that the guests are doing some of the cooking, sharing the labor of preparing the holiday meal. People still do this today. When several households combine to celebrate the day, it is often a communal event with shared cooking responsibilities.

This clan's Thanksgiving is a great family gathering. At least one of the participants in the ritual, a college student, has had to travel a considerable distance on horseback to be there for the feast.

And it is not just the grandmothers, their children, and their childrens' children who gather together. A family of six living next door joins them. Five orphans cared for by Reverend Smith participate, as do two of the students from his school whose families live too far away for them to journey back for their own feast. Four elderly and unattached women "who have no longer homes or children of their own & so came to us," are also partaking of the feast.

This is another aspect of Thanksgiving that should be familiar to the modern reader. In every media market the news on Thanksgiving Day is sure to feature footage of the city's poor and homeless being treated to Thanksgiving dinner. Charity in 1779 began at home. One invited those known poor to sit at one's own table and share one's own feast.

Still, though people today provide dinner to the poor at arm's length through the offices of the modern bureaucratic state and large charitable foundations, the concept of feeding the poor at Thanksgiving remains a strong Thanksgiving custom.

Miss Smith gives a detailed account of what could not be served at the feast because of the war and the British Blockade. They had to do without and compromise in some respects. But there is no genuine deprivation in this family.

Raisins, which would normally be imported from Europe or the wine islands, could not be bought by "neither love nor money." They substituted dried pitted red cherries in the mince pie and the pudding.

"Uncle Simeon still had some spices in store." But they all had to be used in the pies. There was nothing, apparently, in the way of cinnamon and nutmeg left for the pudding. The result was that the pudding, normally a plum pudding with suet, raisins, cinnamon, and nutmeg, was a haphazard affair with the cherries and "a jar of West India preserved ginger which chanced to be left of the last shipment which Uncle Simeon had from there." So this was a using up of the dregs of the pre-war stocks. Nevertheless, Miss Smith describes the result as "extraordinary good."

Roast beef apparently was the family's meat of choice on Thanksgiving. It is absent. "None of us have tasted beef these three years back as it all must go to the army, & too little they get, poor fellows." Another wartime privation.

One wonders why, if so many dedicated families like this one had not eaten beef for three years, the army was constantly so close to starvation.

"Of course we had no wine. Uncle Simeon has still a cask or two, but it all must be saved for the sick & indeed for those who are well, good cider is a sufficient substitute." Miss Smith means fermented or hard cider, a New England staple since the first orchards were producing enough apples. With the trade with Madeira and the Canary Islands cut off, even this prosperous family, used to imported wines, falls back on the locally produced cider.

There are so many guests at this dinner that the dining room is quite packed. "Even that big room had no space to spare when we were all seated." This will be familiar, too, to the modern reader who has tried to squeeze twelve people into a dining space designed for eight.

Servants do the work of serving the family and guests. This is an interesting contrast to the Christmas custom in England at the time, when the family's faithful servants would sit at the table themselves. But one presumes that the servants got to enjoy Thanksgiving dinner afterwards. Even modest families at this time employed servants, so we should not read too much into this. These are locally prosperous people, but not grandees.

With regard to the menu for the day, it is very clear that the family tries very hard to stick to traditions handed down from generation to generation. "Everything was GOOD, though we did have to do without some things that ought to be used,"(my emphasis). We see in that sentence that a strong custom was in place, one that the Smith family, at least, strived to maintain year-after-year.

Because these are farm people, and fairly self-sufficient, they are fairly well able to keep to their customs, except for a few ingredients unavailable due to the war and the blockade. We can discern in Miss Smith's description something of what the menu should have been, as well as what it was.

The meal should have featured roast beef as the main entree at each of the two tables. Instead, there was a haunch of venison (itself known to have been served at the first Thanksgiving dinner in 1621) on each table. The secondary meat was a turkey on one table, and a goose on the other. Notice that turkey is distinctly in a supporting role, not the star. Then there was a pigeon pie on each table. This evolved into chicken pie in later years.

There was an "abundance of good vegetables," but only one is specified. This one is making its first appearance on the Thanksgiving table of this family: "sellery." It was eaten raw and Miss Smith recorded that it was thought to be "very good served with meats."

The seed her Uncle Simeon obtained just before the war shut off trade with England (perhaps violating various non-importation covenants called for by the Continental and Provincial Congresses, as well as local Committees of Safety). The result was ready for the table in three years. Uncle Simeon hoped to have enough celery in 1780 to give family members his surplus.

One can assume a few other vegetable dishes from what we know of Massachusetts' agriculture of the time. We can assume that pumpkin, diced, boiled, and served as a vegetable with vinegar or butter (or both), and spices would have been on the table. Onions, perhaps creamed, perhaps baked in a pie with cheese and bacon would have been present. Peas might well have been there, though they might have been dried. Cranberries, sweetened with sugar and boiled into a sauce, were also likely. Applesauce would have been very likely. A bread sauce or dressing for the poultwhether also likely.

What we cannot tell is whether these vegetables were served as they were, or as what the period called "made dishes." Was corn present? If so, was it served on the cob or in the form of a corn custard? Were the onions creamed, or baked into a pie? Were the peas dried and served as pease pudding, or fresh? Miss Smith fails us in this regard.

There was undoubtedly bread also. The bread would very likely have been based on a mixture of rye flour grown along the Taunton River and corn meal. The more expensive wheat bread would be unlikely, as trade with Pennsylvania, its largest source, would be difficult and limited.

Wine, probably Madeira or Canary would normally have been on the table. But the Blockade and the need to conserve what wine they had for medicinal purposes rendered that impossible. So apple cider was substituted, to Miss Smith's approbation, recorded earlier. The fact that imported wine was normally served at the Thanksgiving table of this family is an indication of its prosperity. Less well-to-do citizens of Massachusetts would not have thought cider on the table a privation.

The meal seems, from the absence of conflicting evidence, to have been served as a single remove or course, instead of the English custom of two removes followed by dessert. And the sweets seem to have been reserved for the dessert table, as they are mentioned last. In England, the custom was to mix in sweets with the savory foods served in the first two removes, and then have a light dessert of fruit, nuts, wine, and maybe a little cake.

Dessert of course was based on the pie. If Miss Smith is providing a complete catalog, there were three types served. Undoubtably, given the numbers around the tables, there several of each type. Mince pie, with dried cherries instead of raisins, we already knew about. Pumpkin pie was of course present. And there was an apple tart, presumably an apple pie lacking the top crust.

But pies were not the only dessert served. There may have been cakes, as Miss Smith mentions baking pies and cakes at her home. But "cakes" could have several meanings in the 18th century. The word could mean bread, or what the 21st century would call cookies ("Shrewsbury Cakes," were in fact, cookies), or cakes as we know them. In any case, Miss Smith does not specify.

But about puddings she is specific. We know that there were at least two served. The first was the New England favorite, Indian Pudding: molasses, cornmeal, flour, sugar, and spices. Its presence indicates that, despite the blockade, there was enough imported molasses on hand. New Englanders used so much of that commodity that not only would they have had much stockpiled, but illicit trade through Canada for it might have continued despite the war. There is evidence of such an illicit trade that the British military was virtually unable to stop.

The second pudding should have been plum pudding, but for the wartime conditions that force the family to substitute the suet pudding with ginger and cherries. The presence of plum pudding on a Thanksgiving table in Massachusetts is a cause for discussion. Plum pudding of course is a staple of the English Christmas celebration. But as Thanksgiving grew in importance in New England, and as Puritan religious fervor lessened in the early 18th century, plum pudding and mince pie made the trek from Christmas, which New Englanders would remain chary of until the 1810s at the earliest, to the holiday they celebrated in either late November or December, Thanksgiving.

It was the absence of Christmas celebration that led to the adoption of some of its cherished food customs for Thanksgiving. The reasons for the slow acceptance of Christmas in new England society are admirably set out in Stephen Nissenbaum's book, The Battle For Christmas.

On a similar note, we see on the guest list that six members of the neighboring Livingston family were present. "They had never seen a Thanksgiving dinner before, having been used to keep Christmas Day instead, as is the wont in New York and Province."

That single sentence speaks volumes about the interplay between the two holidays at that time. Miss Smith provides confirmation, if any were needed, that in 1779, Thanksgiving was still a New England custom. Christmas was celebrated in New York, but not Thanksgiving. In New England, Thanksgiving was celebrated, but not Christmas, except at the margins of society.

But within 50 years of Miss Smith's diary entry, New York would be celebrating Thanksgiving, and New England, Christmas. So that in the Northeast, there would be two-family oriented holidays, each with some pre-Christian customs still attached to them, that would be celebrated within a month of each other.

How this family and its connections marked Thanksgiving in 1779 resembles our own celebrations in other ways as well. One of the most obvious is the formal giving of thanks to God.

Reverend Smith that morning presided over a Thanksgiving service at the meetinghouse. We are told by Miss Smith that the day was bitterly cold, and that Reverend Smith did not tarry over the service. It probably consisted of little more than a reading of the governor's proclamation of the day of thanksgiving, the singing of a few Psalms appropriate to the message of giving thanks, and a short sermon on point.

Miss Smith does not say so, but undoubtably there was grace said before the dinner as well. After dinner, Reverend Smith "led us in prayer, remembering all absent friends before the throne of grace."

Today, this aspect of the holiday has declined somewhat. There are still Thanksgiving prayer services said in almost every city and town. But they are not necessarily on Thanksgiving morning (a time in New England for high school football games and watching the Macy's Parade in New York on television). And they are very likely to be ecumenical in nature today, since no one denomination can fill its church with the number of people willing to come out for this service.

Most families, even those in which grace is said on no other day of the year, at least go through the form of saying grace before Thanksgiving Dinner. Catholic families have the crutch of a short standardized grace that does not let the food get cold while gratitude to God is being expressed.

We note that the Smith's dinner must have started in early-mid afternoon. "We did not rise from the table until it was quite dark." That means the long dinner ended around 4-5 pm. So, with a late-morning prayer service at the meetinghouse, and a time for recovery afterwards, dinner probably started around 1-2 pm, which would have been the customary time for starting dinner in a moderately upscale Massachusetts household in 1779 anyway.

What the family did after dinner would also be familiar to moderns with a living memory of the time before television. "We all got round the fire as close as we could, & cracked nuts, & sang songs, & told stories. At least some told and others listened."

Today most families don't have working fireplaces, but central heating instead. Today they gather around the television and watch some family-oriented programming that is still offered by some of the networks on that day.

But in 1779, before electricity, central heating, and television, the members of the family provided their own entertainment. Such is the case with the few modern families that eschew television, even for special occasions.

It is the elders of the Smith clan who lead the storytelling. "You know nobody can exceed the two Grandmothers at telling tales of all the things they have seen themselves, & repeating those of the early years of New England & even some of Old England, which they had heard in their youth from their elders." This is very much what one would expect.

This passing on of oral tradition is sagely recommended by Reverend Smith. "My Father says it is a goodly custom to hand down all worthy deeds & traditions from Father to Son, as the Israelites were commanded to do about the Passover & as the Indians have always done, because the Word that is spoken is remembered longer than the one that is written."

Thus we see in the Thanksgiving Dinner described by Juliana Smith a great deal of similarity to our own modern day feast. A modern person transported back in time to that table would implicitly grasp what was going on, and probably be more familiar with it than the members of the refugee Livingston Family were. Some items on the menu have varied. And with television and movies, the mode of entertaining the family has changed.

But the customs are still similar enough to be quite familiar. There was, and is, a gathering together of family, thanks to God, generosity to the poor, a great harvest feast including turkey and pumpkin pie, and intimate and jovial family time.

One other thing has not changed from that Thanksgiving Day to this. "The pumpkin pies, apple tarts, & big Indian Pudding lacked for nothing save appetite by the time we had got round to them."

An excellent illustration of this is the Thanksgiving dinner described in her diary by Juliana Smith, the daughter of Massachusetts minister Reverend Smith in 1779. It is published nearly in full in We Gather Together, by Ralph and Adelin Linton, and published by Henry Schuman of New York in 1949 at pages 73-77.

This little-studied diary entry shows that the pattern for the American Thanksgiving celebration that people in the early 21st century continue to observe was in place even at the time of the nation's founding.

The dinner took place in the third year of the Revolutionary War, but reflects little wartime privation. Indeed for a country engaged in a great conflict to establish its independence, one is struck by the normality of the celebration. There is a prayer for absent friends, but one doubts that this prosperous family has supplied much in the way of cannon fodder for Washington's army. One son of military age is instead at college.

The Smith clan was a fairly prosperous one, but not great merchants. One of Juliana's uncles was a doctor, another an apparently prosperous farmer. Her father was the local Congregationalist minister.

Given the family's level of prosperity, it would be reasonable to question the typicality of their Thanksgiving feast. One must ask how representative their celebration is of their region and time. The participants in the Thanksgiving ritual we will closely observe all seem to be familiar with their expected roles, even when they do not come from the same household or class. So we can at least say that this mode of celebration was familiar to these people. But larger characterizations regarding typicality would require evidence outside the diary.

Such evidence does exist. It corroborates the contention that the Thanksgiving gathering described by Juliana Smith was indeed typical in its broad outlines, though perhaps more elaborate than most.

Miss Smith begins her description with some facets of the celebration that will be familiar to the modern householder. "This year, it was Uncle Simeon's turn to have the dinner at his house". So this family group, which by modern standards is rather large, is in the habit of rotating the responsibility for hosting the annual feast. This is a reasonable arrangement given the size and composition of the family group.

The titular heads of the family are the two grandmothers. Their children and their spouses, and their childrens' children form the core of the family group. In addition to them are neighbors, orphans, and stranded students, old people with no place else to celebrate the day, and servants.

Given such a large group, and the prosperity of at least two branches of the family, it would be entirely reasonable to share the responsibility for hosting this ritual gathering, not putting too much of the burden on any one branch year after year.

This custom speaks to the absence of any controlling pater familias, a Squire Bracebridge, if you like, who would not hear of Thanksgiving being celebrated anywhere but in the ancestral seat which he occupies. One wonders if this would be the case if one of Juliana Smith's grandfathers were still alive.

"All the baking of pies and cakes was done at our house & we had the big oven heated & filled twice each day for three days before it was all done". Yes, this is very familiar to moderns hosting a family gathering for Thanksgiving.

Food preparation is time-consuming. Then, without food processors, canned pumpkin, standardized measurements, a hundred utensils and conveniences, or pretty much unfailingly accurate and reliable ovens, it was more so. Three days seems reasonable for making all the pies for such a large gathering. Even today, with all the conveniences in the kitchen, a large meal like this needs to be started days in advance. The difference is in cold storage. There was no refrigeration per se, but the New England weather in late November was often chilly enough to make the cold storage of a farmhouse adequate to the task.

Also note that the guests are doing some of the cooking, sharing the labor of preparing the holiday meal. People still do this today. When several households combine to celebrate the day, it is often a communal event with shared cooking responsibilities.

This clan's Thanksgiving is a great family gathering. At least one of the participants in the ritual, a college student, has had to travel a considerable distance on horseback to be there for the feast.

And it is not just the grandmothers, their children, and their childrens' children who gather together. A family of six living next door joins them. Five orphans cared for by Reverend Smith participate, as do two of the students from his school whose families live too far away for them to journey back for their own feast. Four elderly and unattached women "who have no longer homes or children of their own & so came to us," are also partaking of the feast.

This is another aspect of Thanksgiving that should be familiar to the modern reader. In every media market the news on Thanksgiving Day is sure to feature footage of the city's poor and homeless being treated to Thanksgiving dinner. Charity in 1779 began at home. One invited those known poor to sit at one's own table and share one's own feast.

Still, though people today provide dinner to the poor at arm's length through the offices of the modern bureaucratic state and large charitable foundations, the concept of feeding the poor at Thanksgiving remains a strong Thanksgiving custom.

Miss Smith gives a detailed account of what could not be served at the feast because of the war and the British Blockade. They had to do without and compromise in some respects. But there is no genuine deprivation in this family.

Raisins, which would normally be imported from Europe or the wine islands, could not be bought by "neither love nor money." They substituted dried pitted red cherries in the mince pie and the pudding.

"Uncle Simeon still had some spices in store." But they all had to be used in the pies. There was nothing, apparently, in the way of cinnamon and nutmeg left for the pudding. The result was that the pudding, normally a plum pudding with suet, raisins, cinnamon, and nutmeg, was a haphazard affair with the cherries and "a jar of West India preserved ginger which chanced to be left of the last shipment which Uncle Simeon had from there." So this was a using up of the dregs of the pre-war stocks. Nevertheless, Miss Smith describes the result as "extraordinary good."

Roast beef apparently was the family's meat of choice on Thanksgiving. It is absent. "None of us have tasted beef these three years back as it all must go to the army, & too little they get, poor fellows." Another wartime privation.

One wonders why, if so many dedicated families like this one had not eaten beef for three years, the army was constantly so close to starvation.

"Of course we had no wine. Uncle Simeon has still a cask or two, but it all must be saved for the sick & indeed for those who are well, good cider is a sufficient substitute." Miss Smith means fermented or hard cider, a New England staple since the first orchards were producing enough apples. With the trade with Madeira and the Canary Islands cut off, even this prosperous family, used to imported wines, falls back on the locally produced cider.

There are so many guests at this dinner that the dining room is quite packed. "Even that big room had no space to spare when we were all seated." This will be familiar, too, to the modern reader who has tried to squeeze twelve people into a dining space designed for eight.

Servants do the work of serving the family and guests. This is an interesting contrast to the Christmas custom in England at the time, when the family's faithful servants would sit at the table themselves. But one presumes that the servants got to enjoy Thanksgiving dinner afterwards. Even modest families at this time employed servants, so we should not read too much into this. These are locally prosperous people, but not grandees.

With regard to the menu for the day, it is very clear that the family tries very hard to stick to traditions handed down from generation to generation. "Everything was GOOD, though we did have to do without some things that ought to be used,"(my emphasis). We see in that sentence that a strong custom was in place, one that the Smith family, at least, strived to maintain year-after-year.

Because these are farm people, and fairly self-sufficient, they are fairly well able to keep to their customs, except for a few ingredients unavailable due to the war and the blockade. We can discern in Miss Smith's description something of what the menu should have been, as well as what it was.

The meal should have featured roast beef as the main entree at each of the two tables. Instead, there was a haunch of venison (itself known to have been served at the first Thanksgiving dinner in 1621) on each table. The secondary meat was a turkey on one table, and a goose on the other. Notice that turkey is distinctly in a supporting role, not the star. Then there was a pigeon pie on each table. This evolved into chicken pie in later years.

There was an "abundance of good vegetables," but only one is specified. This one is making its first appearance on the Thanksgiving table of this family: "sellery." It was eaten raw and Miss Smith recorded that it was thought to be "very good served with meats."

The seed her Uncle Simeon obtained just before the war shut off trade with England (perhaps violating various non-importation covenants called for by the Continental and Provincial Congresses, as well as local Committees of Safety). The result was ready for the table in three years. Uncle Simeon hoped to have enough celery in 1780 to give family members his surplus.

One can assume a few other vegetable dishes from what we know of Massachusetts' agriculture of the time. We can assume that pumpkin, diced, boiled, and served as a vegetable with vinegar or butter (or both), and spices would have been on the table. Onions, perhaps creamed, perhaps baked in a pie with cheese and bacon would have been present. Peas might well have been there, though they might have been dried. Cranberries, sweetened with sugar and boiled into a sauce, were also likely. Applesauce would have been very likely. A bread sauce or dressing for the poultwhether also likely.

What we cannot tell is whether these vegetables were served as they were, or as what the period called "made dishes." Was corn present? If so, was it served on the cob or in the form of a corn custard? Were the onions creamed, or baked into a pie? Were the peas dried and served as pease pudding, or fresh? Miss Smith fails us in this regard.

There was undoubtedly bread also. The bread would very likely have been based on a mixture of rye flour grown along the Taunton River and corn meal. The more expensive wheat bread would be unlikely, as trade with Pennsylvania, its largest source, would be difficult and limited.

Wine, probably Madeira or Canary would normally have been on the table. But the Blockade and the need to conserve what wine they had for medicinal purposes rendered that impossible. So apple cider was substituted, to Miss Smith's approbation, recorded earlier. The fact that imported wine was normally served at the Thanksgiving table of this family is an indication of its prosperity. Less well-to-do citizens of Massachusetts would not have thought cider on the table a privation.

The meal seems, from the absence of conflicting evidence, to have been served as a single remove or course, instead of the English custom of two removes followed by dessert. And the sweets seem to have been reserved for the dessert table, as they are mentioned last. In England, the custom was to mix in sweets with the savory foods served in the first two removes, and then have a light dessert of fruit, nuts, wine, and maybe a little cake.

Dessert of course was based on the pie. If Miss Smith is providing a complete catalog, there were three types served. Undoubtably, given the numbers around the tables, there several of each type. Mince pie, with dried cherries instead of raisins, we already knew about. Pumpkin pie was of course present. And there was an apple tart, presumably an apple pie lacking the top crust.

But pies were not the only dessert served. There may have been cakes, as Miss Smith mentions baking pies and cakes at her home. But "cakes" could have several meanings in the 18th century. The word could mean bread, or what the 21st century would call cookies ("Shrewsbury Cakes," were in fact, cookies), or cakes as we know them. In any case, Miss Smith does not specify.

But about puddings she is specific. We know that there were at least two served. The first was the New England favorite, Indian Pudding: molasses, cornmeal, flour, sugar, and spices. Its presence indicates that, despite the blockade, there was enough imported molasses on hand. New Englanders used so much of that commodity that not only would they have had much stockpiled, but illicit trade through Canada for it might have continued despite the war. There is evidence of such an illicit trade that the British military was virtually unable to stop.

The second pudding should have been plum pudding, but for the wartime conditions that force the family to substitute the suet pudding with ginger and cherries. The presence of plum pudding on a Thanksgiving table in Massachusetts is a cause for discussion. Plum pudding of course is a staple of the English Christmas celebration. But as Thanksgiving grew in importance in New England, and as Puritan religious fervor lessened in the early 18th century, plum pudding and mince pie made the trek from Christmas, which New Englanders would remain chary of until the 1810s at the earliest, to the holiday they celebrated in either late November or December, Thanksgiving.

It was the absence of Christmas celebration that led to the adoption of some of its cherished food customs for Thanksgiving. The reasons for the slow acceptance of Christmas in new England society are admirably set out in Stephen Nissenbaum's book, The Battle For Christmas.

On a similar note, we see on the guest list that six members of the neighboring Livingston family were present. "They had never seen a Thanksgiving dinner before, having been used to keep Christmas Day instead, as is the wont in New York and Province."

That single sentence speaks volumes about the interplay between the two holidays at that time. Miss Smith provides confirmation, if any were needed, that in 1779, Thanksgiving was still a New England custom. Christmas was celebrated in New York, but not Thanksgiving. In New England, Thanksgiving was celebrated, but not Christmas, except at the margins of society.

But within 50 years of Miss Smith's diary entry, New York would be celebrating Thanksgiving, and New England, Christmas. So that in the Northeast, there would be two-family oriented holidays, each with some pre-Christian customs still attached to them, that would be celebrated within a month of each other.

How this family and its connections marked Thanksgiving in 1779 resembles our own celebrations in other ways as well. One of the most obvious is the formal giving of thanks to God.

Reverend Smith that morning presided over a Thanksgiving service at the meetinghouse. We are told by Miss Smith that the day was bitterly cold, and that Reverend Smith did not tarry over the service. It probably consisted of little more than a reading of the governor's proclamation of the day of thanksgiving, the singing of a few Psalms appropriate to the message of giving thanks, and a short sermon on point.

Miss Smith does not say so, but undoubtably there was grace said before the dinner as well. After dinner, Reverend Smith "led us in prayer, remembering all absent friends before the throne of grace."

Today, this aspect of the holiday has declined somewhat. There are still Thanksgiving prayer services said in almost every city and town. But they are not necessarily on Thanksgiving morning (a time in New England for high school football games and watching the Macy's Parade in New York on television). And they are very likely to be ecumenical in nature today, since no one denomination can fill its church with the number of people willing to come out for this service.

Most families, even those in which grace is said on no other day of the year, at least go through the form of saying grace before Thanksgiving Dinner. Catholic families have the crutch of a short standardized grace that does not let the food get cold while gratitude to God is being expressed.

We note that the Smith's dinner must have started in early-mid afternoon. "We did not rise from the table until it was quite dark." That means the long dinner ended around 4-5 pm. So, with a late-morning prayer service at the meetinghouse, and a time for recovery afterwards, dinner probably started around 1-2 pm, which would have been the customary time for starting dinner in a moderately upscale Massachusetts household in 1779 anyway.

What the family did after dinner would also be familiar to moderns with a living memory of the time before television. "We all got round the fire as close as we could, & cracked nuts, & sang songs, & told stories. At least some told and others listened."

Today most families don't have working fireplaces, but central heating instead. Today they gather around the television and watch some family-oriented programming that is still offered by some of the networks on that day.

But in 1779, before electricity, central heating, and television, the members of the family provided their own entertainment. Such is the case with the few modern families that eschew television, even for special occasions.

It is the elders of the Smith clan who lead the storytelling. "You know nobody can exceed the two Grandmothers at telling tales of all the things they have seen themselves, & repeating those of the early years of New England & even some of Old England, which they had heard in their youth from their elders." This is very much what one would expect.

This passing on of oral tradition is sagely recommended by Reverend Smith. "My Father says it is a goodly custom to hand down all worthy deeds & traditions from Father to Son, as the Israelites were commanded to do about the Passover & as the Indians have always done, because the Word that is spoken is remembered longer than the one that is written."

Thus we see in the Thanksgiving Dinner described by Juliana Smith a great deal of similarity to our own modern day feast. A modern person transported back in time to that table would implicitly grasp what was going on, and probably be more familiar with it than the members of the refugee Livingston Family were. Some items on the menu have varied. And with television and movies, the mode of entertaining the family has changed.

But the customs are still similar enough to be quite familiar. There was, and is, a gathering together of family, thanks to God, generosity to the poor, a great harvest feast including turkey and pumpkin pie, and intimate and jovial family time.

One other thing has not changed from that Thanksgiving Day to this. "The pumpkin pies, apple tarts, & big Indian Pudding lacked for nothing save appetite by the time we had got round to them."

Labels: Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving Menu

Having a substantial gathering for Thanksgiving Day? Think about this:

Appetizer Course

Brie With Table Water Crackers

Goose Liver Pate With Club Crackers

Pepperoni & Cheddar Cheese on Rye Rounds

Sausage Puffs

Cranberry Cheddar Snacks

Relish Course

Cranberry Apple Orange Relish

Apple Sauce

Pickled Watermelon Rind

Tomato Aspic With Horseradish Sauce

Soup Course

Clam Chowder

Entree Course

Large Roast Turkey or Hotel-Style Turkey Breast

Herbed Dressing

Turkey Gravy (made from the giblets and spicy)

Butternut Squash with Maple Sugar & Cinnamon

Baked Sweet Potatoes

Sweet Corn Ears

Cranberry Sauce

Carrot Pudding

Onion Pie

Mushrooms In Cream

Corn Custard

Harvard Beets

Nottingham Yam Pudding

Chicken Pie

Breads

Beaten Biscuits With Sage

Corn Muffins

Crescent Rolls

Buttermilk Biscuits With Cheese

Sally Lunn Bread (great toasted later)

Pumpkin Butter

Apple Butter

Butter

Pre-Dessert

A Basket of Walnuts & Hazelnuts

Date and Nut Bars

Figs

Stilton & Brie

Dessert

Pumpkin Pie With Cointreu Cream

Apple Pie With Cheddar

Mince Pie with Vanilla Ice Cream

Beverages

Cream Sherry

May Wine

Beaujolais Noveau

Port

Fresh Cider

Dairy Eggnog

Starbucks' French Roast

Post Dinner

Ranitidine, Alka Seltzer, & Tums

Appetizer Course

Brie With Table Water Crackers

Goose Liver Pate With Club Crackers

Pepperoni & Cheddar Cheese on Rye Rounds

Sausage Puffs

Cranberry Cheddar Snacks

Relish Course

Cranberry Apple Orange Relish

Apple Sauce

Pickled Watermelon Rind

Tomato Aspic With Horseradish Sauce

Soup Course

Clam Chowder

Entree Course

Large Roast Turkey or Hotel-Style Turkey Breast

Herbed Dressing

Turkey Gravy (made from the giblets and spicy)

Butternut Squash with Maple Sugar & Cinnamon

Baked Sweet Potatoes

Sweet Corn Ears

Cranberry Sauce

Carrot Pudding

Onion Pie

Mushrooms In Cream

Corn Custard

Harvard Beets

Nottingham Yam Pudding

Chicken Pie

Breads

Beaten Biscuits With Sage

Corn Muffins

Crescent Rolls

Buttermilk Biscuits With Cheese

Sally Lunn Bread (great toasted later)

Pumpkin Butter

Apple Butter

Butter

Pre-Dessert

A Basket of Walnuts & Hazelnuts

Date and Nut Bars

Figs

Stilton & Brie

Dessert

Pumpkin Pie With Cointreu Cream

Apple Pie With Cheddar

Mince Pie with Vanilla Ice Cream

Beverages

Cream Sherry

May Wine

Beaujolais Noveau

Port

Fresh Cider

Dairy Eggnog

Starbucks' French Roast

Post Dinner

Ranitidine, Alka Seltzer, & Tums

Labels: Thanksgiving

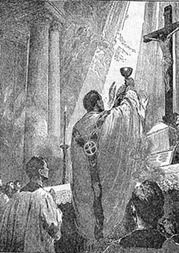

Sunday, November 20, 2011

Stir-Up Sunday

This Sunday, the last of the liturgical year, gets its name from the Collect for today's Mass, which begins, "Stir up, O Lord...". It has nothing to do with cooking.

I will point you to Father Zuhlsdorf for an excellent explanation of the Last Sunday After Pentecost.

I would just add that the Gospel for today, with its discussion of the end of time, and the Last Trumpet, plus the repetition in the various prayers of the first line from the De Profundis (the 129/130th Psalm, one of the Penitential Psalms which is featured most prominently in the Office of the Dead and in the Requiem Mass), "Out of the depths, I cry unto Thee, O Lord...", reminds us that November is the month to pray with special vigor and earnestness for the dead. Next week we begin a new liturgical yeaar, and the season of Advent, switch to purple vestmests and altar cloths, and substitute the Alma Redemptor Mater, for the very familiar Salve Regina as the end of the day Marian hymn. But in the time we have before then, even with the distraction of Thanksgiving, we can still focus on praying for the Poor Souls in Purgatory.

However, since this is about the time you want to make up the mincemeat, plum pudding, and Twelfth Cake so that it will be properly aged and mellowed and inebriated by the Christmas holy days, Stir Up Sunday has taken on the identity as the day you stir up and cook these delicacies.

Let us start with the Mincemeat:

Mincemeat pie is, of course, traditionally associated with Christmas.

But in New England, where the celebration of Christmas was relatively restrained for the first 150 or so years of our history, it was adopted as a Thanksgiving food. Thanksgiving tables in Massachusetts from 1740-1870 often boasted a mince pie. Just goes to show you that you can't keep a good mince pie down (or a bad one, but that is a different matter).

Today, when you go out picking apples in September or early October, one of the things you can do with the bushels that come home is to make mincemeat, and thus you can begin making ready for both Thanksgiving and Christmas.

You can either freeze the mincemeat in ziploc bags, or bake into pies, and freeze the pies until needed. I prefer the former method. In either case, it is a good thing to beat the holiday rush by getting your mincemeat ready now. If you double-bag the mincemeat, it should keep in the fridge for many months. At Thanksgiving and Christmas, nothing says "home" like a warm mincemeat pie.

This pie was actually outlawed in New England during the earliest period of Massachusetts history, as it is a symbol of Christmas, the celebration of which was also against the law. The pie has been variously known as Neat's Pie, Shrid Pie, Christmas Pie, Mutton Pie, and of course, Mince Pie (which was more or less common by the end of the 18th century). As a staple of English and Irish cuisine, it dates back to medieval times at least.

Little Jack Horner's Christmas Pie, was, of course, mincemeat. The plumb he pulled out with his thumb was in fact the deed to a plundered parcel of Church property, the deed to which, along with many others, was inserted into a huge Christmas Pie to be delivered, by Horner, to Henry VIII. Somehow, the property found its way into the possession of Horner, rather than Henry.

This would be a good time to try to correct a modern misconception. Raisins were known by various regional words in England and Ireland. In parts of England, they are called "figs." In other parts, they are called "plumbs" or "plums." In no case were either what we know as figs or plums ever included in traditional mincemeat, or plum pudding, or fruitcake.

All those recipes you see for plum pudding that call for plums?

Rip them out of your cookbook. Burn the pages, lest others fall into this heresy.

The same with "Figgy Pudding" recipes with figs. All you want are raisins and currants. Got it? Figgy Pudding does not have figs. Plum Pudding does not have plums. They are, in fact, the same thing, and both have raisins.

I am a firm believer that the better the quality of the ingredients you use, the better the finished product will taste. That is why I use sirloin tips rather than suet or stew beef, and fresh orchard cider from Brooksby Farm in peabody, and apples picked that weekend by hand, and by me.

This recipe will make many pies.

If there is a lot of liquid, drain it off and freeze it separately, as it can be served by itself either hot or cold as plum porridge. I suspect that the extra liquid from making mince pie was how that soup got started. Eat the plum porridge in small amounts, as even I would say it is very, very rich.

10 cups chopped apples, preferably freshly picked

4 cups diced sirloin tip meat fried or broiled (I pan fry)

2 cups of beef stock (your own, or canned)

2 cups of fresh sweet apple cider

8 cups of sugar

1 cup of molasses

3 tablespoons of cinnamon

2 teaspoons of ground cloves

4 lemons, rind and juice

3 tablespoons of salt

3 pounds of seedless raisins

1 pound of currants

1/2 pound of citron

1/4 pound candied or fresh orange rind

1/4 pound candied or fresh lemon rind

1 cup brandy (don't use "cooking brandy")

1 cup Captain Morgan's Spiced Rum

at pie-making time

orange flower water, to taste

French brandy, to taste

Captain Morgan's, to taste

freshly ground nutmeg

cinnamon-sugar to taste

(No, your teeth will not fall out, at least not right away.)

Chop the apples and beef finely. Pan fry the sirloin tips until medium rare, then dice or shred them into tiny bits. Place the apples and beef into a very large pot with all the remaining measured ingredients.

Simmer slowly for up to three hours, stirring every few minutes.

The aroma is incredible, and will make the house smell like the holidays in no time.

After a few hours, take the mincemeat off the heat, and allow it to cool.

Once the mincemeat has cooled, drain the excess liquid for plum porridge, and freeze it in a separate container (that won't leak in your freezer).

Put the mincemeat into gallon Ziplocs, and freeze.

There should be enough mincemeat for 6-8 9-inch mince pies (or lots of small mincemeat pies).

But the mince pie is so rich, you might want to serve it in tart or individual serving-size pie pans.

When it's time for making the pies, thaw the mincemeat in the refrigerator for a day or two.

Make two short crusts for each pie. Line the pie pan with crust. Add the mincemeat. Pour on some orange flower water, Captain Morgan's, and brandy, dot the pie with some small pats of butter, and a grating of fresh nutmeg to taste.

I use fairly liberal doses of all in my mince pies.

Put on the top layer of crust, and seal the edges, leaving ventilation slits in the top crust.

Bake for 10 minutes at 450 degrees (you may want a drip tray under the pie in the oven), and then for 30 minutes at 350 degrees, but watch the crust carefully. Use of one of those shields that protect the edges is recommended.

When the pie is fresh out of the oven, sprinkle the top with a generous portion of cinnamon-sugar.

Once baked, the pies keep in the fridge for a week.

They taste terrific warm or cold. Vanilla ice cream is great on top. Eggnog Ice Cream would not be too much.

You expect to put on some weight during the holidays. Live a little!

Fruit Cake/Christmas Cake/Twelfth Cake

The recipe that follows is a modified version of Martha Washington's recipe for what she called "Great Cake," or her cake for great occasions. Her recipe calls for taking forty eggs, separating them, and beating the whites to a froth with a bundle of sticks. Well, eggs were smaller then. And the bundle of sticks has long given way to the electric mixer. Thank Heavens!

If you want to try it, read the recipe through first, so that you will be sure to have everything you need.

1 pound raisins

11 oz. currants

1 cup candied orange peel

1 cup candied lemon peel

1 cup citron

1 cup of candied red cherries

1 cup of candied green cherries

good brandy (warning: this is not a recipe for those recovering from a drinking problem)

Put all the fruit into a large bowl, and cover it with the brandy. Cover the bowl, and let the fruit soak in the brandy for a couple of days.

41/2 cups of all purpose flour

1 teaspoon mace

1 teaspoon nutmeg

1 tablespoon cinnamon

1 teaspoon ginger

1 teaspoon ground cloves

4 sticks of butter softened

2 1/2 cups sugar

10 eggs, separated

2 teaspoons lemon juice

1/3 cup of cream sherry

the remainder of the bottle of cream sherry (I use Savory & James: inexpensive but tastes nice)

Once the fruit has soaked for at least 36 hours (sometimes, I let it soak for 5-6 days on the counter), sift together the flour and spices, and set it aside.

Work the butter until it is creamy, then add one cup of sugar a little at a time. Beat it until it is smooth.

Beat the egg yolks until they are thick and light. Then add 1 cup of sugar to the yolks. Add the lemon juice to the yolks after the sugar is added. Combine the yolk mixture with the butter-sugar mixture. Add the rest of the sugar.

Add the flour/spices and 1/3 cup sherry both little-by-little and alternating with each other.

Once all the flour/spices and the 1/3 cup of sherry have been added to the egg yolk/butter/sugar mixture, drain the fruit (I've never tried to drink the brandy, but I don't suppose it would do much harm), and add it also.

Now beat the egg whites until they are stiff. Fold the egg whites into the batter.

Grease and flour a 10-inch tube pan (don't forget to grease the tube itself). Pour the batter into the pan. Put a pan of hot water on the bottom rack of the oven, and pre-heat to 350 degrees. Bake at 350 degrees for 20 minutes. Then reduce heat to 325 degrees and bake for another hour and forty minutes. The cake is done when a knife inserted in it comes out clean.

Turn the cake out gently, and let it cool on a rack. Soak lots of cheese cloth in the rest of the sherry. Wrap the cake in the sherry-soaked cheese cloth, then put it in an airtight Rubbermaid (or other airtight plastic cake container) for three weeks.

Each week, check the cheese cloth to see if it is still moist. If it has dried out, soak it in more cream sherry, and re-apply. The longer the cake cures, the better. Just this past summer, I found in the pantry a Christmas cake made two years ago, and happily sliced it up. It was delicious. All the sugar, spice, and booze in the mix makes it almost as everlasting as the Twinkie, except it improves with age, unlike the Hostess Twinkie.

Martha Washington's Plum Pudding

2 1/2 lb raisins

3/4 c brandy

2 ts cinnamon

1/2 ts cloves

1 ts allspice

2 ts mace

1 1/2 ts nutmeg

1 lb beef suet, minced

1/2 c grated orange peel

1/4 c grated lemon peel

1 lb citron

2 c flour

7 eggs, beaten

2 c sugar

Instructions

According to her time-honored recipe, you take three days to prepare this great concoction.

First, the raisins are cooked until soft. Leave the fruit in