Saturday, October 26, 2013

Our Blessed Lady's Saturday

October Offering to Mary

In spring, we laid a blossom at your feet, The lovely May, O dearest Lady. Now We offer you October, ripe and sweet, A ruddy apple from the spirit's bough! It is our love which gives this fruit its glow; Its flavor is our daily rosary; Our Masses nourished it and helped it grow: It sprang from our joined hearts as from a tree.

Kind Mother, take within your hands today This apple of devotion we have grown, And as you give it to your dear Son say That it is fruit from seed His hand has sown. We offer you October, bright and firm: Oh, may this apple hold no blight, no worm!

Virginia Moran Evans The Magnificat October 1953

Friday, October 25, 2013

Upon Saint Crispin's Day!

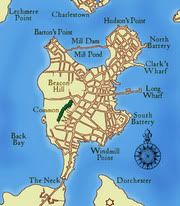

The Battle of Agincourt was fought upon this day, an anniversary those of us whose childhoods were formed around anniversaries of deeds of heroics are inclined to remember.

WESTMORELAND.

O that we now had here

But one ten thousand of those men in England

That do no work to-day!

KING.

What's he that wishes so?

My cousin Westmoreland? No, my fair cousin;

If we are mark'd to die, we are enow

To do our country loss; and if to live,

The fewer men, the greater share of honour.

God's will! I pray thee, wish not one man more.

By Jove, I am not covetous for gold,

Nor care I who doth feed upon my cost;

It yearns me not if men my garments wear;

Such outward things dwell not in my desires.

But if it be a sin to covet honour,

I am the most offending soul alive.

No, faith, my coz, wish not a man from England.

God's peace! I would not lose so great an honour

As one man more methinks would share from me

For the best hope I have. O, do not wish one more!

Rather proclaim it, Westmoreland, through my host,

That he which hath no stomach to this fight,

Let him depart; his passport shall be made,

And crowns for convoy put into his purse;

We would not die in that man's company

That fears his fellowship to die with us.

This day is call'd the feast of Crispian.

He that outlives this day, and comes safe home,

Will stand a tip-toe when this day is nam'd,

And rouse him at the name of Crispian.

He that shall live this day, and see old age,

Will yearly on the vigil feast his neighbours,

And say 'To-morrow is Saint Crispian.'

Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars,

And say 'These wounds I had on Crispian's day.'

Old men forget; yet all shall be forgot,

But he'll remember, with advantages,

What feats he did that day. Then shall our names,

Familiar in his mouth as household words-

Harry the King, Bedford and Exeter,

Warwick and Talbot, Salisbury and Gloucester-

Be in their flowing cups freshly rememb'red.

This story shall the good man teach his son;

And Crispin Crispian shall ne'er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remembered-

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne'er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition;

And gentlemen in England now-a-bed

Shall think themselves accurs'd they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin's day.

Maddy Prior and June Tabor, Agincourt Carol

WESTMORELAND.

O that we now had here

But one ten thousand of those men in England

That do no work to-day!

KING.

What's he that wishes so?

My cousin Westmoreland? No, my fair cousin;

If we are mark'd to die, we are enow

To do our country loss; and if to live,

The fewer men, the greater share of honour.

God's will! I pray thee, wish not one man more.

By Jove, I am not covetous for gold,

Nor care I who doth feed upon my cost;

It yearns me not if men my garments wear;

Such outward things dwell not in my desires.

But if it be a sin to covet honour,

I am the most offending soul alive.

No, faith, my coz, wish not a man from England.

God's peace! I would not lose so great an honour

As one man more methinks would share from me

For the best hope I have. O, do not wish one more!

Rather proclaim it, Westmoreland, through my host,

That he which hath no stomach to this fight,

Let him depart; his passport shall be made,

And crowns for convoy put into his purse;

We would not die in that man's company

That fears his fellowship to die with us.

This day is call'd the feast of Crispian.

He that outlives this day, and comes safe home,

Will stand a tip-toe when this day is nam'd,

And rouse him at the name of Crispian.

He that shall live this day, and see old age,

Will yearly on the vigil feast his neighbours,

And say 'To-morrow is Saint Crispian.'

Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars,

And say 'These wounds I had on Crispian's day.'

Old men forget; yet all shall be forgot,

But he'll remember, with advantages,

What feats he did that day. Then shall our names,

Familiar in his mouth as household words-

Harry the King, Bedford and Exeter,

Warwick and Talbot, Salisbury and Gloucester-

Be in their flowing cups freshly rememb'red.

This story shall the good man teach his son;

And Crispin Crispian shall ne'er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remembered-

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne'er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition;

And gentlemen in England now-a-bed

Shall think themselves accurs'd they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin's day.

Maddy Prior and June Tabor, Agincourt Carol

Wednesday, October 23, 2013

Saint Anthony Mary Claret

Sunday, October 20, 2013

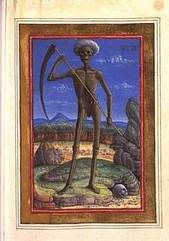

Traditional First Post For Hallowmas

October 20th is when I begin to really get into Hallowmas mode, and I like to begin each year with a quotation from one of my favorite novels from my required reading at prep school.

From the Prologue to Ray Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes, published in 1962.

Ray Bradbury, who died this year, was very much a modern. But his work was not imbued with modernism. You might call his style modernity without modernism. His Fahrenheit 451, which I read eleven years ago for the first time, is one of the most conservative statements in favor of classical learning and against the mainstream pseudo-culture of TV that you will find written in the 20th century.

Something Wicked This Way Comes, Dandelion Wine, and The Illustrated Man show us a most welcome positive view of small town America (with a twist, of course, this is fiction, and imaginative fiction at that). Bradbury's normative themes are refreshing and real and far more authentic to the human experience (while being faithful to the cultural tradition of which they are a part) than the works of hundreds of authors whose books cram the local Barnes & Noble or Borders.

In years past, I searched my local bookstores each year for The Halloween Tree, which I was only familiar with from the animated TV Halloween special done years ago (Leonard Nimoy as the voice of Moonshroud). No luck. Finally picked up a used copy for short money last year and read it for the first time. Loved it!

The difference is that, in 100 years, no one will recall who these authors were, or why what they had to say. But people will still read Bradbury for pleasure.

Others achieve the same plateau of excellence: Tolkien, Eliot, Lewis, Frost, O'Brian, O'Connor, Kirk, Hawthorne, Pope, Wodehouse, Waugh, Faulkner, Wolfe, O'Conner, maybe Rowling. Their stuff will stand the test of time. Not only is Bradbury a friend of what Russell Kirk called "the permanent things," and a friend of Kirk, but his work is part of that cultural patrimony we must pass down.

Bradbury has for me made October 20th a milestone, a day in which Halloween begins to be anticipated. Halloween, the eve of All Saints' and the build-up for the Catholic Day of the Dead, All Souls', has taken some hard knocks, mostly unjustified. Opportunistic modern wiccans and pagans, especially in Salem, have claimed as their own a holiday that has nothing to do with them and their New Age, and never did.

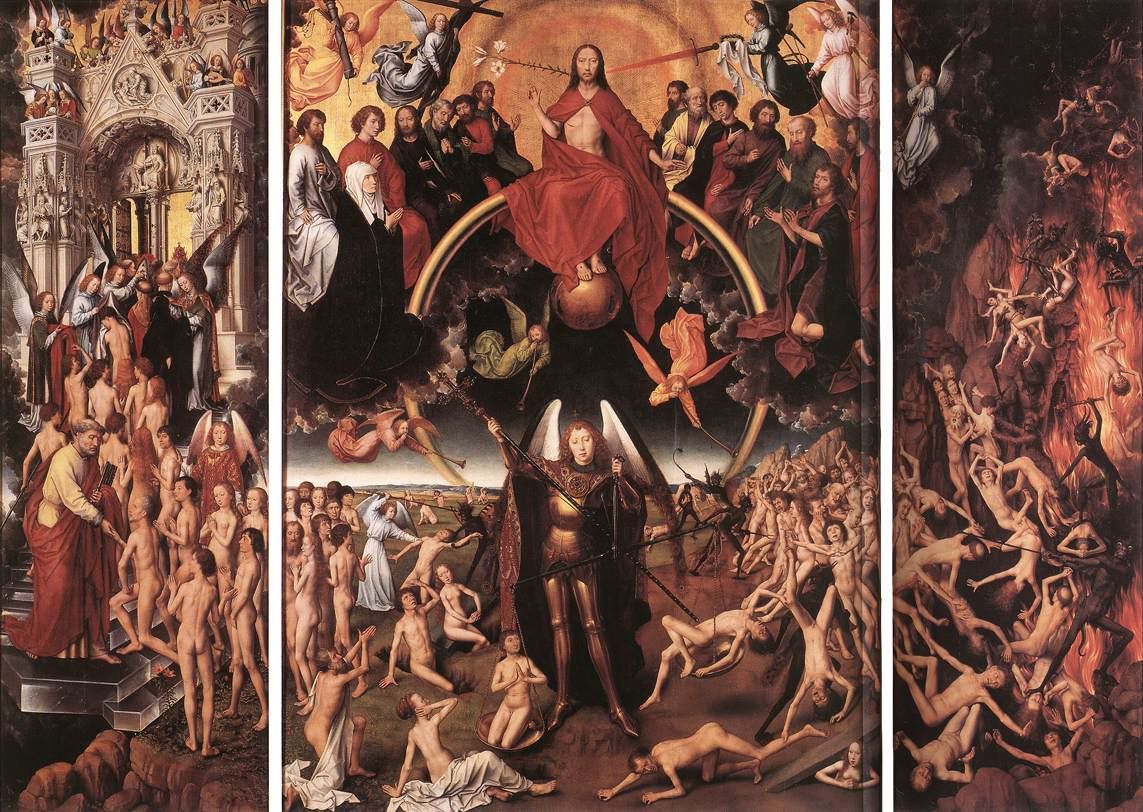

The celebration of the day is Celtic and Christian. It is the dying time of the year, with the harvest almost all in now, and even the green leaves of summer suddenly blazing into brilliant color and then dropping to the ground. The days are growing notably colder and shorter. It is the appropriate time to recall our dead, to think about, and to pray for all the dead. The merry season of Christmas lies ahead. But, as the liturgical year winds down over the next 5 weeks, let us pause to recall death. It is the first of the Four Last Things, after all.

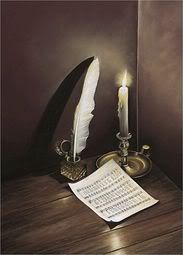

If part of thinking about it is reading old gothic ghost stories over a mug of mulled cider by candlelight in the privacy of one's study, or watching movies about ghosts, witches, vampires, werewolves, and monsters, or impressing the imagination of children by decorating a "haunted house" and handing out enough candy to make them spit out teeth the next day, or carving pumpkins in imitation of the Irish custom of the carved turnip of Jack of the Lantern, or burning leaves at night, there is no harm in it.

But the experience is made richer by remembering the saints of the Church on All Hallows' Day itself, and by praying for the dead, our dead, and the forgotten, unknown poor souls in Purgatory throughout November. And if dressing up as ghosts in bedsheets (I used the "Charlie Brown" costume once or twice as a kid) and going door to door like the people in Celtic villages who dressed up as those who had died during the year did to seek propitiary offerings, or those who, in Christian times, performed the luck-visit ritual of going a'souling, then it is a start.

The important thing is to get people to start to remember the dead. Then build on that foundation. Just getting them to think of the dead as something other than inventory for a graveyard and an object of horror is a necessary start. We will all die, and will want to be remembered and prayed for. Purgatory is no easy thing, if we are lucky enough to get there. So remember the dead, and pray for them, because in time you may be that poor forgotten soul in Purgatory, wishing someone would remember you in their prayers with a longing that we can scarcely conceive.

Memento Mori!

Remember that you will die, too. As you are now, so the dead once were. As the dead are now, so you will one day be.

And the number one thing the dead need is prayers. Prayers, Masses, and Rosaries are of foremost importance for the dead in Purgatory.

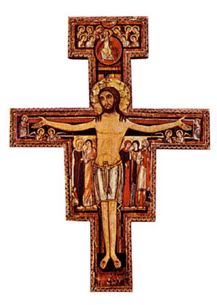

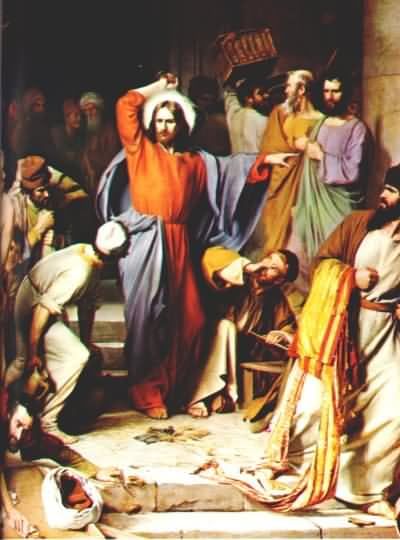

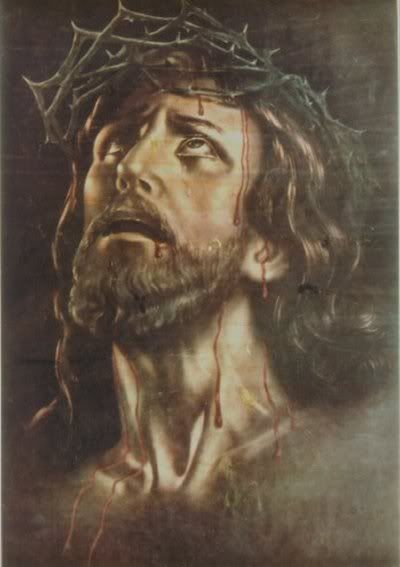

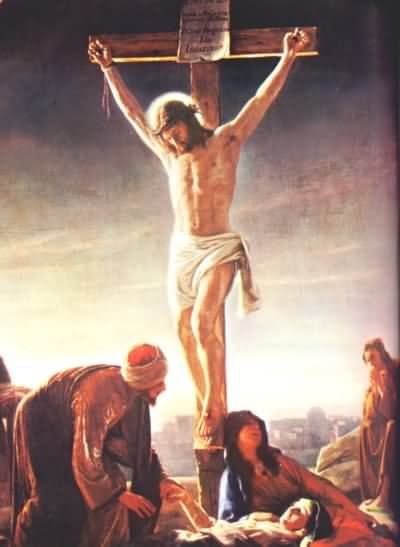

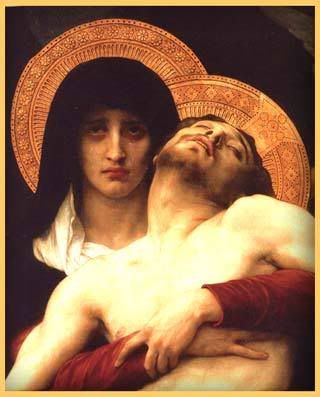

My Jesus, by the sorrows Thou didst suffer in Thine agony in the Garden, in Thy scourging and crowning with thorns, on the way to Calvary, in Thy crucifixion and death, have mercy on the souls in Purgatory, and especially on those that are most forsaken; do Thou deliver them from the terrible torments they endure; call them and admit them to Thy most sweet embrace in paradise.

Amen.

"First of all, it was October, a rare month for boys. Not that all months aren't rare. But there be good and bad, as the pirates say. Take September, a bad month: school begins. Consider August, a good month: school hasn't begun yet. July, well, July's really fine: there's no chance in the world for school. June, no doubting it, June's best of all, for the school doors spring wide and September's a billion years away.

But you take October, now. School's been on a month and you're riding easier in the reins, jogging along. You got time to think of the garbage you'll dump on old man Prickett's porch, or the hairy ape costume you'll wear to the YMCA on the last night of the month. And if it's around October twentieth and everything smoky smelling and the sky orange and ash gray at twilight, it seems Halloween will never come in a fall of broomsticks and a soft flap of bedsheets around corners."

From the Prologue to Ray Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes, published in 1962.

Ray Bradbury, who died this year, was very much a modern. But his work was not imbued with modernism. You might call his style modernity without modernism. His Fahrenheit 451, which I read eleven years ago for the first time, is one of the most conservative statements in favor of classical learning and against the mainstream pseudo-culture of TV that you will find written in the 20th century.

Something Wicked This Way Comes, Dandelion Wine, and The Illustrated Man show us a most welcome positive view of small town America (with a twist, of course, this is fiction, and imaginative fiction at that). Bradbury's normative themes are refreshing and real and far more authentic to the human experience (while being faithful to the cultural tradition of which they are a part) than the works of hundreds of authors whose books cram the local Barnes & Noble or Borders.

In years past, I searched my local bookstores each year for The Halloween Tree, which I was only familiar with from the animated TV Halloween special done years ago (Leonard Nimoy as the voice of Moonshroud). No luck. Finally picked up a used copy for short money last year and read it for the first time. Loved it!

The difference is that, in 100 years, no one will recall who these authors were, or why what they had to say. But people will still read Bradbury for pleasure.

Others achieve the same plateau of excellence: Tolkien, Eliot, Lewis, Frost, O'Brian, O'Connor, Kirk, Hawthorne, Pope, Wodehouse, Waugh, Faulkner, Wolfe, O'Conner, maybe Rowling. Their stuff will stand the test of time. Not only is Bradbury a friend of what Russell Kirk called "the permanent things," and a friend of Kirk, but his work is part of that cultural patrimony we must pass down.

Bradbury has for me made October 20th a milestone, a day in which Halloween begins to be anticipated. Halloween, the eve of All Saints' and the build-up for the Catholic Day of the Dead, All Souls', has taken some hard knocks, mostly unjustified. Opportunistic modern wiccans and pagans, especially in Salem, have claimed as their own a holiday that has nothing to do with them and their New Age, and never did.

The celebration of the day is Celtic and Christian. It is the dying time of the year, with the harvest almost all in now, and even the green leaves of summer suddenly blazing into brilliant color and then dropping to the ground. The days are growing notably colder and shorter. It is the appropriate time to recall our dead, to think about, and to pray for all the dead. The merry season of Christmas lies ahead. But, as the liturgical year winds down over the next 5 weeks, let us pause to recall death. It is the first of the Four Last Things, after all.

If part of thinking about it is reading old gothic ghost stories over a mug of mulled cider by candlelight in the privacy of one's study, or watching movies about ghosts, witches, vampires, werewolves, and monsters, or impressing the imagination of children by decorating a "haunted house" and handing out enough candy to make them spit out teeth the next day, or carving pumpkins in imitation of the Irish custom of the carved turnip of Jack of the Lantern, or burning leaves at night, there is no harm in it.

But the experience is made richer by remembering the saints of the Church on All Hallows' Day itself, and by praying for the dead, our dead, and the forgotten, unknown poor souls in Purgatory throughout November. And if dressing up as ghosts in bedsheets (I used the "Charlie Brown" costume once or twice as a kid) and going door to door like the people in Celtic villages who dressed up as those who had died during the year did to seek propitiary offerings, or those who, in Christian times, performed the luck-visit ritual of going a'souling, then it is a start.

The important thing is to get people to start to remember the dead. Then build on that foundation. Just getting them to think of the dead as something other than inventory for a graveyard and an object of horror is a necessary start. We will all die, and will want to be remembered and prayed for. Purgatory is no easy thing, if we are lucky enough to get there. So remember the dead, and pray for them, because in time you may be that poor forgotten soul in Purgatory, wishing someone would remember you in their prayers with a longing that we can scarcely conceive.

Memento Mori!

Remember that you will die, too. As you are now, so the dead once were. As the dead are now, so you will one day be.

And the number one thing the dead need is prayers. Prayers, Masses, and Rosaries are of foremost importance for the dead in Purgatory.

My Jesus, by the sorrows Thou didst suffer in Thine agony in the Garden, in Thy scourging and crowning with thorns, on the way to Calvary, in Thy crucifixion and death, have mercy on the souls in Purgatory, and especially on those that are most forsaken; do Thou deliver them from the terrible torments they endure; call them and admit them to Thy most sweet embrace in paradise.

Amen.