Friday, April 21, 2006

Prayer For Our Holy Father

I missed our Holy Father's 79th birthday, and the 1st anniversary of his pontificate.

May his pontificate stretch over 3 decades, may he be blessed with excellent good health of body, mind and soul. May he who was reluctant to become our Supreme Pontiff not be worn down, discourged, enervted,or prematurely aged by the task, but instead let him be rejuvented by it. May it add years of excellent good health to his life, and may he come to enjoy and relish the job, and look forward to doing it every day. May it not lead to the condemnation of the soul of Joseph Alois Ratzinger, but to his salvation. May his every appointment as bishop, cardinal, or head of Vatican department, his every teaching and pronouncement, every pronouncement of everyone serving under him and the departments themselves, reflect the views he has expressed over the last 25 years as both head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and as a private theologian, and the reputation he developed as "God's Rottweiler," because Heaven knows the Church needs a thorough cleansing from the filth, faithlessness, and modernism that has grown so strong in the last 50 years. May he and we be blessed by Pope Benedict XVI's long and fruitful pontificate, a pontificate which will increase the holiness and orthodoxy of all Catholics, and one which will see the day when all who remain professing the Catholic Faith to be of one mind on such important social issues as abortion, birth control, euthanasia, assisted suicide, mercy killing, cloning, embryonic stem cell research, the sanctity of marriage, fornication, adultery, pornography, feminism, swinging, polygamy, polyamory, bestiality, gay marriage, gay civil unions, civil unions generally, gay adoptions, and the gay lifestyle generally.

That is the prayer I say every morning for our Holy Father after I mention his published intentions for the month. No wonder my morning holy hour usually takes an hour and fifteen minutes!

Happy Belated Birthday And Anniversary, Papa!!!

Ad Multos Annos!!!

May his pontificate stretch over 3 decades, may he be blessed with excellent good health of body, mind and soul. May he who was reluctant to become our Supreme Pontiff not be worn down, discourged, enervted,or prematurely aged by the task, but instead let him be rejuvented by it. May it add years of excellent good health to his life, and may he come to enjoy and relish the job, and look forward to doing it every day. May it not lead to the condemnation of the soul of Joseph Alois Ratzinger, but to his salvation. May his every appointment as bishop, cardinal, or head of Vatican department, his every teaching and pronouncement, every pronouncement of everyone serving under him and the departments themselves, reflect the views he has expressed over the last 25 years as both head of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and as a private theologian, and the reputation he developed as "God's Rottweiler," because Heaven knows the Church needs a thorough cleansing from the filth, faithlessness, and modernism that has grown so strong in the last 50 years. May he and we be blessed by Pope Benedict XVI's long and fruitful pontificate, a pontificate which will increase the holiness and orthodoxy of all Catholics, and one which will see the day when all who remain professing the Catholic Faith to be of one mind on such important social issues as abortion, birth control, euthanasia, assisted suicide, mercy killing, cloning, embryonic stem cell research, the sanctity of marriage, fornication, adultery, pornography, feminism, swinging, polygamy, polyamory, bestiality, gay marriage, gay civil unions, civil unions generally, gay adoptions, and the gay lifestyle generally.

That is the prayer I say every morning for our Holy Father after I mention his published intentions for the month. No wonder my morning holy hour usually takes an hour and fifteen minutes!

Happy Belated Birthday And Anniversary, Papa!!!

Ad Multos Annos!!!

As Closing And Cutting Back Parishes Causes Crises Of Faith Here In Boston,

Wednesday, April 19, 2006

Archdiocese Releases Detailed Financial Report

Cardinal O'Malley is forthright in noting that declining revenue comes from the pervert priest crisis, and the parish closings.

It is a fact of life that many people, faced with the closure of the parish church that has been the center of their community for generations, as well as the site for all important family events, weddings, baptisms, first Communions, first confessions, confirmations, and funerals, instead of cheerily attending Mass at the parish they are referred to, drop out of Catholic life altogether. The closing of a parish church is a butcher's axe hack at the life of the community, the family, and the individual. So, as people react to such closure with an "up yours!" attitude, can we be surprised? Bostonians are very provincial. We like our own little platoons, and don't cheerfully switch to the parish across town just to make the green eyeshade folks at the chancery happy.

Applying this basic fact to the most important of the parishes that remain officially on the Archdiocese's To Be Closed list, Holy Trinity, one can see that the detriments of closing far out-weigh the benefits. First of all, there will be another vigil, appeal, and protracted battle in every forum available to the people who attend Holy Trinity, which involves significant costs as well as bad publicity. Second, let us look at what will happen to the money currently floiwng to the Archdiocese from Holy Trinity attendees.

There is the small German community which, on paper anyway, is the host parish. Now admittedly, this is a small group, but it is the only German community p[arish in New England, and the people who attend there do not all come from the territory of the Archdiocese. Close their parish, and they and the monies they contribute weekly will stay home. Perhaps as many as one-third will stop attending Catholic Mass at all. Others will no longer patronize parishes in the Archdiocese.

Then there is the much larger tradiitonal Latin Mass community. On paper, they are mere attendees without the rights in canon law of parishioners, though that needs to be clarified by Rome. Close Holy Trinity, and three things will happen with this group. Many, like the people in the German community, come from the territory of other dioceses, like New Hampshire and Fall River, where there is no indult Mass. They will stay home and not patronize any parish in the Archdiocese. They and their generosity will be gone.

Next, a very large percentage of the Latin Mass community will head directly to the SSPX chapels without passing Go and taking their weekly contributions with them. No money will flow from the Archdiocese from them. Besides which, with the Holy Father intent, by his own writings and the report of many reliable sources, on both reconciliation with the SSPX and a broader allowance of the Latin Mass generally, is it wise to play with the Latin Mass community here in Boston? Why strengthen the SSPX locally when the Holy Father is trying to either reconcile its leaders or lure their flock back into full Communion with Rome without the leaders?

Third, many will go back to their territorial parishes, but they will be royally ticked off, and will be withholding contributions that go to the Archdiocese. They will grind their teeth and suffer through the Novus Ordo as best they can, but they will make sure that the Archdiocese will pay for it.

And then there is the fourth group, though it is probably a small one among the committed Latin Mass devotees. This group will react just like many people in other closed parishes, and drop affiliation with the Roman Catholic Church altogether. I think by now it is estblished that an unreasonably large percentage of people who have been part of parishes that have been closed will do just that. Great pastoral care of souls it is to allow that to happen!

And for what benefit? Close Holy Trinity, and a developer would bid some 3 Million Dollars, maybe 5 for it. It is then turned into condos for well-heeled South End gay couples, so that they have the double benefit of great location and saying "This is what we think of the Catholic Church: Ha! Ha! Ha!, we just did it where the high altar of the most conservative Catholic church in Massachusetts used to be--guess who won!" at the same time. Meanwhile, one of the Archdiocesan bureaucracies blows through the 3-5 million in six months, or it goes to enrich the plaintiffs' lawyers in yet another round of pervert priest litigation settlements. Did the Archdiocese really benefit from closing the parish?

So maybe the Archdiocese is figuring out that cutting the parish base was a terrible idea that ended up hurting it financially more than the crumbs from the realty sales helped.

While the priest shortage, the other reason given for the parish closures is significant, it is not bad enough yet to justify closing so many parishes. There are enough active diocesan priests to have more than one priest at every parish. And that does not even count the religious priests, and the possibility of inviting in new orders not yet present in Boston to staff parishes. If the chancery took its blinders off and cooled the animosity towards the traditonal Latin Mass long enough to do more than jerk the knee, they would understand that the traditionalists are one more community that needs to be ministered to, and that there are orders of good, faithful, orthodox priests in full communion with Rome that would be more than happy to send a priest to Boston (and a darned fine one, I'm sure) to take on that ministry in union with the Cardinal and the Holy Father. And that would put no strain on the limited priest resources of the Archdiocese.

So what is the case for closing Holy Trinity again, and what, again, is the case for keeping the FSSP out of Boston?

It is a fact of life that many people, faced with the closure of the parish church that has been the center of their community for generations, as well as the site for all important family events, weddings, baptisms, first Communions, first confessions, confirmations, and funerals, instead of cheerily attending Mass at the parish they are referred to, drop out of Catholic life altogether. The closing of a parish church is a butcher's axe hack at the life of the community, the family, and the individual. So, as people react to such closure with an "up yours!" attitude, can we be surprised? Bostonians are very provincial. We like our own little platoons, and don't cheerfully switch to the parish across town just to make the green eyeshade folks at the chancery happy.

Applying this basic fact to the most important of the parishes that remain officially on the Archdiocese's To Be Closed list, Holy Trinity, one can see that the detriments of closing far out-weigh the benefits. First of all, there will be another vigil, appeal, and protracted battle in every forum available to the people who attend Holy Trinity, which involves significant costs as well as bad publicity. Second, let us look at what will happen to the money currently floiwng to the Archdiocese from Holy Trinity attendees.

There is the small German community which, on paper anyway, is the host parish. Now admittedly, this is a small group, but it is the only German community p[arish in New England, and the people who attend there do not all come from the territory of the Archdiocese. Close their parish, and they and the monies they contribute weekly will stay home. Perhaps as many as one-third will stop attending Catholic Mass at all. Others will no longer patronize parishes in the Archdiocese.

Then there is the much larger tradiitonal Latin Mass community. On paper, they are mere attendees without the rights in canon law of parishioners, though that needs to be clarified by Rome. Close Holy Trinity, and three things will happen with this group. Many, like the people in the German community, come from the territory of other dioceses, like New Hampshire and Fall River, where there is no indult Mass. They will stay home and not patronize any parish in the Archdiocese. They and their generosity will be gone.

Next, a very large percentage of the Latin Mass community will head directly to the SSPX chapels without passing Go and taking their weekly contributions with them. No money will flow from the Archdiocese from them. Besides which, with the Holy Father intent, by his own writings and the report of many reliable sources, on both reconciliation with the SSPX and a broader allowance of the Latin Mass generally, is it wise to play with the Latin Mass community here in Boston? Why strengthen the SSPX locally when the Holy Father is trying to either reconcile its leaders or lure their flock back into full Communion with Rome without the leaders?

Third, many will go back to their territorial parishes, but they will be royally ticked off, and will be withholding contributions that go to the Archdiocese. They will grind their teeth and suffer through the Novus Ordo as best they can, but they will make sure that the Archdiocese will pay for it.

And then there is the fourth group, though it is probably a small one among the committed Latin Mass devotees. This group will react just like many people in other closed parishes, and drop affiliation with the Roman Catholic Church altogether. I think by now it is estblished that an unreasonably large percentage of people who have been part of parishes that have been closed will do just that. Great pastoral care of souls it is to allow that to happen!

And for what benefit? Close Holy Trinity, and a developer would bid some 3 Million Dollars, maybe 5 for it. It is then turned into condos for well-heeled South End gay couples, so that they have the double benefit of great location and saying "This is what we think of the Catholic Church: Ha! Ha! Ha!, we just did it where the high altar of the most conservative Catholic church in Massachusetts used to be--guess who won!" at the same time. Meanwhile, one of the Archdiocesan bureaucracies blows through the 3-5 million in six months, or it goes to enrich the plaintiffs' lawyers in yet another round of pervert priest litigation settlements. Did the Archdiocese really benefit from closing the parish?

So maybe the Archdiocese is figuring out that cutting the parish base was a terrible idea that ended up hurting it financially more than the crumbs from the realty sales helped.

While the priest shortage, the other reason given for the parish closures is significant, it is not bad enough yet to justify closing so many parishes. There are enough active diocesan priests to have more than one priest at every parish. And that does not even count the religious priests, and the possibility of inviting in new orders not yet present in Boston to staff parishes. If the chancery took its blinders off and cooled the animosity towards the traditonal Latin Mass long enough to do more than jerk the knee, they would understand that the traditionalists are one more community that needs to be ministered to, and that there are orders of good, faithful, orthodox priests in full communion with Rome that would be more than happy to send a priest to Boston (and a darned fine one, I'm sure) to take on that ministry in union with the Cardinal and the Holy Father. And that would put no strain on the limited priest resources of the Archdiocese.

So what is the case for closing Holy Trinity again, and what, again, is the case for keeping the FSSP out of Boston?

April 19, 1775

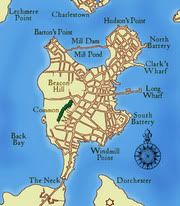

Today, we shall examine the events of April 19, 1775 through the eyes of contemporaries. The images are all engravings made in the summer of 1775 by two Connecticut militiamen, Amos Doolittle and Ralph Earl. Notice that Doolitle, the engraver who made the initial prints (Earl painted some of the scenes later) has the tree on Lexington Green fully leafed out, as it would be in summer. In this part of Massachusetts, trees are almost never fully by April 19th. These images need to be used with some care, especially with regard to troop formations. Doolittle and Earl were not eyewitnesses to the fighting, but must have talked with American survivors of the clashes. But for topography, it seems pretty clear that Doolittle and Earl were careful to give us a view of what the scene of the battle looked like in the summer of 1775.

The first is the fight on Lexington Green. First the topography. The Green and its environs were rather less built-up in 1775 than it is today. However, Doolittle depicts two buildings on the Common that are no longer there. The first is the meetinghouse, the building behind the head of the British officer on horseback. Just to its right is the belfry, a replica of which is now on the hill, across the road behind the sole tree. The Green of 1775 is much more barren than that of 2006. Many large trees are now planted around the perimeter. The Green itself in 1775 was much more rough and uneven. Today it is graded, and equipped with a manicured lawn. Then, there were many sudden slopes, and the grass would have been much more uneven, since grazing animals were the only landscapers on the scene. The tree in the center is approximately the site of the current Minuteman statue, thought to depict Captain John Parker. To the left of the tree is the Buckman Tavern and its outbuildings and stone walls. The Tavern still stands today as one of the most treasured legacies of the battle, and proudly bears the scars of musketball holes from gunfire directed at the building by British troops. About where the stonewalls are is the current location of Routes 4&225 as the come to merge with Massachusetts Avenue about where the tree is or just beyond it in this view.

Doolittle shows us the Lexington militia company of the First Middlesex Regiment. They were not "minutemen," as the town of Lexington had never obeyed the Provincial Congress' request that town militia companies designate a high percentage of the most able and best-equipped men as minutemen, and organize them as seperate minuteman companies, with their own regimental organization. This is a topic that former NATO Commander General James Galvin in his doctoral dissertation, The Minute Men: Myths And Realities of the First Fight explored in detail.

What Doolittle shows us is timid militia in the act of running away. And there was a fair amount of that. What he does not show is the confusion of the situation. Not only were the militia company members on the Green, but there were at least 40 spectators around the Green. Some of the militia obeyed their captain's last-second order to pull back. Some did not. Some were just arriving on the scene from all angles. And once the firing started, many of them were firing back, including from within the Buckman Tavern (which it why it became a target for British musketry). As part of the rebel propaganda effort of 1775, the image of Lexington militia firing on the light infantry was deliberately suppressed. But at least 8 militiamen later testified that thye did fire back, once Concord claimed to have offered the first forcible resistance to the British. But we know that one Private Johnston of the 10th Regiment's light company was wounded by rebel fire, and that Major Pitcairn's horse was hit in two places.

If Doolittle has made the American side of the engagement too placid, he has done the same with the British side. He shows us two companies that have deployed from column into line, with a third coming up behind them. The rest of the British troops are marching serenely by. There is one officer on horseback, and he seems to be commanding the troops to fire. In reality, the lead company, the 10th light infantry, had just deployed from column into line, and was surging unevenly forward at a high rate of speed. The 4th King's Own light company, second in the column, had just made the deployment (on the command, "Form, Front" the rear files of the marching column--probably a column of twos given the limited width of the country road--came forward and formed around the first 4 men in the column to either side of them) and was racing to come up on line with the Tenth's company. The third company, the Corps of Marines very large light company (almost 160% of the size of the marching regiments' light companies) was still in column. The other three companies (I'm speculating here, but the identities of the other three companies may have been those of the 23rd Royal Welch Fuziliers, 5th Regiment of Foot, and 52nd Regiment of Foot) were trying to round the meetinghouse and then form on the left of the 10th. But since they were further back in the column, they were not involved in the initial exchange of shots, but piled into the melee afterwards.

Instead of just one officer on hoseback, there were many. Pitcairn's advance guard had picked up the refugees of Major Mitchell's mounted patrol of at least 6 officers and a few other ranks who could ride and could be trusted on such detached duty (the chaps who had captured Paul Revere a few hours before in Lincoln) as well as the point officers, who we know included Ensign Henry deBerniere of the 10th, who had scouted the roads a month before for General Gage, Lt. William Sutherland of the 38th Regiment, a volunteer on the expedition who would later be an aide de camp to General Sir Henry Clinton, and Surgeon's Mate Simms of the 43rd Regiment, as well as two loyalist guides, and a small party of Royal Artillerymen commanded by Lt. Grant in a chaise. In fact, the plethora of mounted officers from various regiments probably contributed to the confusion. Some American sources indicate that, while Pitcairn, himself a Marine officer and unfamiliar to almost all the men under his command that morning, was up front ordering the rebels to drop their guns and go home, other officers behind him were giving contradictory commands, and may have ordered concentrated fire after hearing the first shot. We know Sutherland's horse took off with him, and carried him a good way into the rebel lines, such as they were, up what is now Routes 4 &225.

So this primitive artifact of American history has enormous use. But it is mostly in telling us what Lexington Green and its environs looked like, rather than in wht the Battle of Lexington Green actually looked like.

Next up is Doolittle's rendering of the British marching into Concord, and searching the town for the hidden rebel supplies. For this one, the study of the topography is almost all that is important. In the foreground, two officers, Lt. Col. Smith of the 10th, and Major Pitcairn of the Corps of Marines have climbed the steep hill in Concord center, which then, as now, was a graveyard. Today, it is called Sleepy Hollow, and a section of it contains the graves of many important figures in American letters: Thoreau, Emerson, Hawthorne, and Alcott.

Across the Bay Road is the Wright Tavern, the reddish building. Smith made this his headquarters. It stands today, but though it once housed a tourist trp gift shop, is now a rel estte office.

To the left of the tavern is the Concord Meetinghouse. It was here that the rebel Provincial Congress had been meeting at some days before the expediiton. Today, that building no longer stands, but the successor Congregational church, complete with picturesque New England steeple, stands in its place.

Behind both is body of water that exists today only as an underground stream. It was called the Mill Pond. Smith's grenadiers dumped barrels of flour into it, but did not do a good job of it, dumping the barrels in whole, instead of breaking them up, so that the rebels were able to salvage much of it. Today, that Mill Pond covers much of downtown Concord, including The Concord Shop/The Cheese Shop, a great place for buying cheeses, pates, and other gourmet delights. It is the only true gourmet shop I know of in the Boston area.

On the far right of the scene is another building of some importance, the home of Dr. George Minot. Dr. Minot, an ardent rebel, treated the wounded of both sides after the bttle. One soldier of the 4th King's Own's light company, wounded at the North Bridge, died there. The house is part of what is now the Colonial Inn, the taproom of which I have reveled in many a time, in uniform: so much so that, when I took dates to dine in the dining room, the host was surprised to see me not wearing British uniform. The Minot House portion of the Inn is said to be haunted to this day by the ghost of Dr. Minot.

As to what the British troops are doing, Doolittle does a fair job. I think he is, in the time-honored tradition of artists, depicting things that happened at different times in the same scene. We have the British troops marching into town. But the formation they are in is impossible. They are marching on a company front. The road was never so wide to allow that. Most likely, they came in in a column of two.

Men are already dispersed about the town seeking out rebel supplies, and dumping things into the Mill Pond. And Col. Smith and Major Pitcirn are on the hilltop, looking nervously at the growing concentration of rebel troops in the vicinity of the North Bridge. The British entered the town about 8am, and the fight at the bridge was over by 11am. Perhaps Smith is considering just how many troops to send to search Barrett's Farm beyond the bridge. In the end, he settled on 4 companies of light infantry to search, while three more held the environs of the bridge in their rear.

By the way, the road running down the center of the engraving into the distance leads to the South Bridge. Concord Academy and the Concord Library are on the route today, both on the right of the road. Two companies of grenadiers were sent to hold that bridge, and the commanding Lee's Hill next to it, under the command of Capt. Munday Pole of the 10th. Lee's Hill is better known today as part of Nashawtuc Country Club.

First my apologies for switching to black and white for the third engraving, but the Univesity of Michigan does not offer the last two on line, and I had to find other sources. Surprisingly, after a long Google image search, this was the best I could come up with.

This is the engagement at Concord's Old North Bridge. The antagonists are about 400 Massachusetts militia and minutemen from three different regiments, and about 120 light infantry organized in 3 companies (from the 4th, 10th, and 47th Regiments of Foot)under the command of the senior company commander, Walter Sloane Laurie of the 47th. The Americans are under the command of Colonel James Barrett of Concord, whose farm is, at this minute, being fruitlessly searched for hidden military supplies.

To set the stage, the Americans had withdrawn as the British entered town, and had lingered near the bridge, then moved to Punkatasset Hill, about a mile to the far right of this view.There, their numbers grew, while the British headed off for Barrett's Farm, held the bridge in the rear of the searching party, and searched the downtown Concord area.

The rebels were emboldened by their growing numbers, and marched closer to the bridge. When they did that, the companies of the 4th and 10th, which had been stationed in the vicinity of the Buttrick House, pulled back the quarter mile to the bridge itself, but oddly stayed on the far side, rather than pulling back over the bridge and preparing a proper defense.

The Americans were now next to the Buttrick House, in the area now known as The Muster Field. From there, they had a good view of the bridge (if they had artillery, they could have made the bridge totally indefensible from there) and an obstructed view of what was going on in Concord. Over the trees, smoke began to rise, as the grenadiers were burning a cache of wooden trenchers and barrels, as well as the carriages for 2 cannon they had found. Thinking that the troops were burning the town, the Concord men pressured Barrett into ordering a march to the center.

Meanwhile, Laurie, feeling uneasy at the growing numbers of armed rebels so close to his position, sent one of the officers from Major Mitchell's patrol to Col. smith, asking for additional help. Smith's initial reply was that he thought 3 companies more than adequate to hold a bridge. And in fact he was right. If Laurie had thought through his tactical problem and looked at the position he had to defend, he ought to have been able to hold it against the much larger force for a decently long time, especially since his opponents were militia. But on Laurie's second appeal, he ordered his two reserve companies of grenadiers up the road to the bridge, but retarded their march by marching himself at their head. Several British accounts note the fact that Smith was a very fat, heavy man, whose best marching days were in 1775 long behind him. They would be too late to do anything to help Laurie, except cover his retret back to Concord Center.

Now we can look at the topography of the scene Doolittle is depicting. The Concord River and the North Bridge are the dominant features here. The current bridge is a replica, the third, I believe, of the bridge that stood there in 1775. Doolittle's engraving was the primary source for later generations so that they could rebuild the bridge pretty much as it was in 1775.

The terrain was much more open in 1775 than it is today. On the British side in particular, there are large trees now planted along the road leading to the Bridge, that were not there in 1775. Though the National Park Service is keen to replicate the 1775 environment as closely as possible, those trees are likely to stay, as they were planted as a memorial. On the British side of the bridge, there is today an obelisk marking the events. On the American side, there is Daniel Chester

French's The Minuteman statue, which is the symbol for the US National Guard.

The Concord River is fairly shallow, but in the spring, it tends to flood dramatically, with the surrounding fields often innundated especially in late March or early April. Hence Emerson's line, "By the rude bridge that arched the flood."

If you were in the middle foreground of the engraving, and walked directly out of it, you would run into the Old Manse, the parsonage for the town of Concord. In 1775, the parson was one William Emerson, the grandfather of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Parson Emerson, though he would serve with American troops later, and die of the Camp Fever the next year, on this day was trying to keep the women and children who had clustered at the parsonage calm. His biggest worry seems to have been his own wife, who apparently was close to a nervous breakdown. The troops did not enter the parsonage, though it would have made an excellent defensive bastion against raw militia without artillery, and would have enabled them to hold open the bridge, and the return route of the 4 companies of their comrades at Barrett's Farm. Doolittle may have sketched the scene from Emerson's description from a window of the Old Manse. Later, the Manse would be the home of Ralph Waldo Emerson, who later rented it to Nathaniel Hawthorne.

This copy of the engraving cuts off the far left side, which depicts two houses on the ridge just below the Muster Field. They belonged to Captain David Brown, and were occupied by his very large family. Captain Brown, at that moment, was busy commanding one of Concord's three companies of minutemen Captain Brown was a superstitious sort, and, in the years after the battle, never crossed the bridge at night without singing a Psalm tune at the top of his lungs. The houses are no longer standing, but extensive archeological investigations have been made on their sites.

The one house you can see clearly is the Buttrick House, in the center of the engraving above the bridge. Actually, it is a quarter mile from the bridge, and out of musket range. John Buttrick was a major in the regiment of minutemen from Concord and the surrounding towns, and was leading the rebel column's march on the bridge. The house still stands today.

What we obviously do not see is the Buttrick Mansion, built by Buttrick's prosperous descendants about 150 yards in front of the original Buttrick House. It today is the NPS Visitors' Center for the Old North Bridge site, and has lovely gardens. One of my favorite places on earth.

One feature ought to be noted, and that is the dry-laid stone wall, of typical New England design, which ran, and runs along both sides of the road leading to the bridge on the British side of the river. One can only opine that, had Laurie made good use of the time and manpower he had, he could have set 75 men to making a breastwork along the river bank with those stones, while a dozen more pulled up half the stringers of the bridge. No armed body could have crossed the river then, in daylight against opposition.

Along the path we see the British retreating on, which is the road that leads back to Concord Center, just a hundred yards off the right edge of the engraving, the road curved sharply south to avoid a fairly high hill with woods (now) and a stone wall near its top. Again, Laurie could have used that position to hem in any American forces that got over the bridge. Two companies along that ridge, and one in the Old Manse, and Barrett's troops would haved been stopped up like liquid in a corked bottle. Two companies of grenadiers appraching along the road, and the 4 companies at Barrett's Farm coming from the rear, and Concord Bridge could have been an ignominious defeat, rather than the site of America's first military victory. Barrett was no fool. Once he repelled Laurie, he had his forces occupy that ridge, and watched ominously as Smith milled around pointlessly on the road below, before marching back to town, abandoning Parsons and the 4 companies now returning from Barrett's Farm to the pleasure of the rebels.

And the idea of using the stone walls to make a breastwork to defend the river bank was raised by Ensign Jeremy Lister, a volunteer serving with the 10th's light company, but rejected by Laurie.

Now let us see what Doolittle is showing us. We see a lot of British troops in the road before the bridge. a few right at the edge of the bridge are firing. A few are behind them facing the enemy, but most are heading, with more or less celerity, for Concord. This is very accurate. The best way to defend a bridge is to envelop it with fire from both sides. Laurie opted for a technique called Street Firing, which sends a large volume of fire down a central channel, like a road. The platoons or companies line up one behind the other on company or platoon front. The front company fires, then files to either side and moves back to the rear of the column, reloads, and waits for their opportunity to fire and file back again. You can advance by street firing, retreat by street firing, or hold by street firing. Laurie's apparent intention was to hold. It is used in urban warfare. It could be a good way to defend a bridge,it the men are well-versed in it, and the officers know what commands to give. That was Laurie's downfall.

The British command situation at the bridge was terrible. There were three companies, each of which should have been commanded by a captain with two lieutenants supporting him. The 4th's company's captain was on detached duty commanding a large detachment that General Gage had sent to Marshfield some months before to encourge the active loyalists of that town. In his absence, the senior lieutenant, Edward Thornton Gould commanded the company, though in practice he would have sought consent from our old friend John Barker, the junior subaltern of the company, whose diary entries we looked at last April here. So that company was commanded by two junior officers.

Then there was the second company in the column, that of the 10th Regiment. Its captain, Lawrence Parsons wasn't there either. Being the senior captain in the 7 companies sent to the bridge (one has the feeling that Smith assigned the companies for the mission to be sure that his own light company commander was senior) he took four companies, not including his own, to Barrett's Farm to search. In his absence, the 10th's light company was commanded by Lt. Waldron Kelly, who was actually the junior lieutenant assigned to the company. the senior lieutenant, Edward Hamilton, apparently feigned illness on hearing of the expedition, either out of cowardice, or alcoholic indisposition. Ensign Lister, assigned to one of the battalion companies of the 10th, volunteered to replace Hamilton on the expedition, for the honor of the regiment. He was a keen young officer, with a shrewd tactical sense, but he wasn't a regular company officer of the light infantry. By the way, one of my reenacting personae was Ensign Jeremy Lister.

The company of the 47th was commanded by Captain Laurie, but since he was the senior officer present, he wasn't commanding his company, but had to leave it to his two lieutenants while he commanded the whole.

Now two extra officers were present, Captain Lumm of Mitchell's patrol, who was mounted, and acted as Laurie's messenger and go-between with Col. Smith in Concord Center since he wasn't assigned to any of the units there, and Lt. William Sutherland, who had volunteered to act as one of the pointmen on the expedition, but was, like Lister (and Lumm), a battalion company officer. Sutherland had intended to go on with just his servant to join Parsons at Barrett's Farm, but the approach of the rebels to the Muster Field earlier had made that too hazardous, so he stayed at the bridge.

Of these officers and men, few seemed to have been familiar with Street Firing drill. It was among the options available for maneouvers in the 1764 Manual, but not every regiment trained in it. One would have thought that, during the long winter in Boston garrison in 1774-1775, everyone would have been practiced in this, in case of rebel attack on the town of Boston. But this does not seem to have been the case. Barker, in his diary, seems to have no idea that Street Firing was what Laurie had in mind. Lister objected to that as the proper tactic. And Sutherland tried to countermand Laurie with the men of his own company, and ordered them into the meadows on either side of the road. Amazingly about a half-dozen of the men of Laurie's own company obeyed the strange officer, and followed him over the stone wall into the meadows. And they paid heavily for this. And these are the three officers at the bridge who left accounts, besides Laurie's official report.

Aside from unrfamiliarity with the tactic, the other damning features of its use here were that the lane in which the troops were drawn up was very narrow. You can't really tell from Doolittle, but at the time, the lane was no wider than the width of a wagon, with stonewalls on either side. It would be difficult for the lead half company (let alone full company) to fire then retire to the rear. The walls and the men behind them would prevent that. Today, the stone walls have been pushed back very considerably, and the tqactic can be executed by reenactment troops very easily.

The other factor that lead to the failure of this tactic was that the enemy had room to maneouvre on the opposite bank. Street Firing implies tht the enemy is confined to a narrow channel, and that pouring a heavy volume of fire down that channel will cause many casualties and, more importantly, disruption.

But in this case, especially on their left flank, the Americans had plenty of room to fan out from their column, and did do. This enabled them to pour a very heavy volume of fire into the troops packed into the narrow roadway. Moreover, this fanning out enabled them to envelop the British troops in the roadway. The fact that they had a 4-1 numerical superiority helped, too. Had the light infantry been crouching behind a breastwork made from the stonewalls, they could have held the bridge impervious to most of the rebel fire, until reinforcements showed up.

The troops who were the most exposed suffered the worst. First of all, the officers, on the sides of their companies. In the first company, Gould was hit in the heel. In the 10th, Kelly was hit in the arm. In the 47th, Lt. Hull received a mortal wound in the chest (he died the next day). On the flank, Sutherland took a shallow but ugly wound across the chest. Until he got back to Boston, and a surgeon's care, he was thought to be dying. The men from the 47th who went into the fields with Sutherland from the back of the column were disproportionately wounded. And in the very front company, that of the 4th, one man was killed on the spot, one so badly wounded that he had to be left there (he was, within minutes, attacked by a hatchet-wielding American who left him there to die, leading to reports that the rebels were scalping British wounded--reports that fueled genuine British atrocities later in the day, like killing prisoners in Menotomy), and one more was carried back to Concord, where he died despite Dr. Minot's ministrations.

Doolittle shows us the Americans firing more generally, I think, than the British. After Gould's half company fired, the men of the 4th could not get out of the way of the rest of the column. The men behind them could not get forward to step into their place, so they all just went to the right about, and headed back to Concord, carrying most of the 9 wounded men with them.

You can make out the leading American, who is probably Major Buttrick, who leapt into the air, crying out, "Fire, fellow soldiers, for God's sake, fire!"

Though the British fired first here (the first shot coming from one of the men Sutherland led into the Manse field) their fire was fairly ineffective. Only one company, that of the 4th, could fire without hitting their own men (except for the few men in the meadows). And it may be that the 4th was divided into two half-companies, so that only the first 16 or so men could fire. Two Americans were killed, including the captain of the leading minuteman company, Issac Davis of Acton (whose men were first because Davis, a blacksmith, made sure every man in his company had a good bayonet for his musket, and who may have had something of a premonition of his death when he marched off that morning, as he had turned back to his wife, and said, "Take good care of the children."). Three more were wounded, but that did nothing to slacken the volume of fire coming from the American side of the bridge.

So what Doolittle is showing us is the first American military victory. If it was duly recognized as such, the needless 19th century feud between Lexington and Concord as to which town offered the first forcible resistance to the Britihs might have been avoided. The Lexington men did fire back at the British, and therefore offered the first forcible resistance. But Concord was the scene of America's first military victory. Laurels enough to go around.

I'll analyze this one of Lord Percy's relief column rescuing Col. Smith's command in Lexington later. This entry is so long, it has taken most of my blogging time for the last two days already. I'll post a link back when I do it. Promise.

The first is the fight on Lexington Green. First the topography. The Green and its environs were rather less built-up in 1775 than it is today. However, Doolittle depicts two buildings on the Common that are no longer there. The first is the meetinghouse, the building behind the head of the British officer on horseback. Just to its right is the belfry, a replica of which is now on the hill, across the road behind the sole tree. The Green of 1775 is much more barren than that of 2006. Many large trees are now planted around the perimeter. The Green itself in 1775 was much more rough and uneven. Today it is graded, and equipped with a manicured lawn. Then, there were many sudden slopes, and the grass would have been much more uneven, since grazing animals were the only landscapers on the scene. The tree in the center is approximately the site of the current Minuteman statue, thought to depict Captain John Parker. To the left of the tree is the Buckman Tavern and its outbuildings and stone walls. The Tavern still stands today as one of the most treasured legacies of the battle, and proudly bears the scars of musketball holes from gunfire directed at the building by British troops. About where the stonewalls are is the current location of Routes 4&225 as the come to merge with Massachusetts Avenue about where the tree is or just beyond it in this view.

Doolittle shows us the Lexington militia company of the First Middlesex Regiment. They were not "minutemen," as the town of Lexington had never obeyed the Provincial Congress' request that town militia companies designate a high percentage of the most able and best-equipped men as minutemen, and organize them as seperate minuteman companies, with their own regimental organization. This is a topic that former NATO Commander General James Galvin in his doctoral dissertation, The Minute Men: Myths And Realities of the First Fight explored in detail.

What Doolittle shows us is timid militia in the act of running away. And there was a fair amount of that. What he does not show is the confusion of the situation. Not only were the militia company members on the Green, but there were at least 40 spectators around the Green. Some of the militia obeyed their captain's last-second order to pull back. Some did not. Some were just arriving on the scene from all angles. And once the firing started, many of them were firing back, including from within the Buckman Tavern (which it why it became a target for British musketry). As part of the rebel propaganda effort of 1775, the image of Lexington militia firing on the light infantry was deliberately suppressed. But at least 8 militiamen later testified that thye did fire back, once Concord claimed to have offered the first forcible resistance to the British. But we know that one Private Johnston of the 10th Regiment's light company was wounded by rebel fire, and that Major Pitcairn's horse was hit in two places.

If Doolittle has made the American side of the engagement too placid, he has done the same with the British side. He shows us two companies that have deployed from column into line, with a third coming up behind them. The rest of the British troops are marching serenely by. There is one officer on horseback, and he seems to be commanding the troops to fire. In reality, the lead company, the 10th light infantry, had just deployed from column into line, and was surging unevenly forward at a high rate of speed. The 4th King's Own light company, second in the column, had just made the deployment (on the command, "Form, Front" the rear files of the marching column--probably a column of twos given the limited width of the country road--came forward and formed around the first 4 men in the column to either side of them) and was racing to come up on line with the Tenth's company. The third company, the Corps of Marines very large light company (almost 160% of the size of the marching regiments' light companies) was still in column. The other three companies (I'm speculating here, but the identities of the other three companies may have been those of the 23rd Royal Welch Fuziliers, 5th Regiment of Foot, and 52nd Regiment of Foot) were trying to round the meetinghouse and then form on the left of the 10th. But since they were further back in the column, they were not involved in the initial exchange of shots, but piled into the melee afterwards.

Instead of just one officer on hoseback, there were many. Pitcairn's advance guard had picked up the refugees of Major Mitchell's mounted patrol of at least 6 officers and a few other ranks who could ride and could be trusted on such detached duty (the chaps who had captured Paul Revere a few hours before in Lincoln) as well as the point officers, who we know included Ensign Henry deBerniere of the 10th, who had scouted the roads a month before for General Gage, Lt. William Sutherland of the 38th Regiment, a volunteer on the expedition who would later be an aide de camp to General Sir Henry Clinton, and Surgeon's Mate Simms of the 43rd Regiment, as well as two loyalist guides, and a small party of Royal Artillerymen commanded by Lt. Grant in a chaise. In fact, the plethora of mounted officers from various regiments probably contributed to the confusion. Some American sources indicate that, while Pitcairn, himself a Marine officer and unfamiliar to almost all the men under his command that morning, was up front ordering the rebels to drop their guns and go home, other officers behind him were giving contradictory commands, and may have ordered concentrated fire after hearing the first shot. We know Sutherland's horse took off with him, and carried him a good way into the rebel lines, such as they were, up what is now Routes 4 &225.

So this primitive artifact of American history has enormous use. But it is mostly in telling us what Lexington Green and its environs looked like, rather than in wht the Battle of Lexington Green actually looked like.

Next up is Doolittle's rendering of the British marching into Concord, and searching the town for the hidden rebel supplies. For this one, the study of the topography is almost all that is important. In the foreground, two officers, Lt. Col. Smith of the 10th, and Major Pitcairn of the Corps of Marines have climbed the steep hill in Concord center, which then, as now, was a graveyard. Today, it is called Sleepy Hollow, and a section of it contains the graves of many important figures in American letters: Thoreau, Emerson, Hawthorne, and Alcott.

Across the Bay Road is the Wright Tavern, the reddish building. Smith made this his headquarters. It stands today, but though it once housed a tourist trp gift shop, is now a rel estte office.

To the left of the tavern is the Concord Meetinghouse. It was here that the rebel Provincial Congress had been meeting at some days before the expediiton. Today, that building no longer stands, but the successor Congregational church, complete with picturesque New England steeple, stands in its place.

Behind both is body of water that exists today only as an underground stream. It was called the Mill Pond. Smith's grenadiers dumped barrels of flour into it, but did not do a good job of it, dumping the barrels in whole, instead of breaking them up, so that the rebels were able to salvage much of it. Today, that Mill Pond covers much of downtown Concord, including The Concord Shop/The Cheese Shop, a great place for buying cheeses, pates, and other gourmet delights. It is the only true gourmet shop I know of in the Boston area.

On the far right of the scene is another building of some importance, the home of Dr. George Minot. Dr. Minot, an ardent rebel, treated the wounded of both sides after the bttle. One soldier of the 4th King's Own's light company, wounded at the North Bridge, died there. The house is part of what is now the Colonial Inn, the taproom of which I have reveled in many a time, in uniform: so much so that, when I took dates to dine in the dining room, the host was surprised to see me not wearing British uniform. The Minot House portion of the Inn is said to be haunted to this day by the ghost of Dr. Minot.

As to what the British troops are doing, Doolittle does a fair job. I think he is, in the time-honored tradition of artists, depicting things that happened at different times in the same scene. We have the British troops marching into town. But the formation they are in is impossible. They are marching on a company front. The road was never so wide to allow that. Most likely, they came in in a column of two.

Men are already dispersed about the town seeking out rebel supplies, and dumping things into the Mill Pond. And Col. Smith and Major Pitcirn are on the hilltop, looking nervously at the growing concentration of rebel troops in the vicinity of the North Bridge. The British entered the town about 8am, and the fight at the bridge was over by 11am. Perhaps Smith is considering just how many troops to send to search Barrett's Farm beyond the bridge. In the end, he settled on 4 companies of light infantry to search, while three more held the environs of the bridge in their rear.

By the way, the road running down the center of the engraving into the distance leads to the South Bridge. Concord Academy and the Concord Library are on the route today, both on the right of the road. Two companies of grenadiers were sent to hold that bridge, and the commanding Lee's Hill next to it, under the command of Capt. Munday Pole of the 10th. Lee's Hill is better known today as part of Nashawtuc Country Club.

First my apologies for switching to black and white for the third engraving, but the Univesity of Michigan does not offer the last two on line, and I had to find other sources. Surprisingly, after a long Google image search, this was the best I could come up with.

This is the engagement at Concord's Old North Bridge. The antagonists are about 400 Massachusetts militia and minutemen from three different regiments, and about 120 light infantry organized in 3 companies (from the 4th, 10th, and 47th Regiments of Foot)under the command of the senior company commander, Walter Sloane Laurie of the 47th. The Americans are under the command of Colonel James Barrett of Concord, whose farm is, at this minute, being fruitlessly searched for hidden military supplies.

To set the stage, the Americans had withdrawn as the British entered town, and had lingered near the bridge, then moved to Punkatasset Hill, about a mile to the far right of this view.There, their numbers grew, while the British headed off for Barrett's Farm, held the bridge in the rear of the searching party, and searched the downtown Concord area.

The rebels were emboldened by their growing numbers, and marched closer to the bridge. When they did that, the companies of the 4th and 10th, which had been stationed in the vicinity of the Buttrick House, pulled back the quarter mile to the bridge itself, but oddly stayed on the far side, rather than pulling back over the bridge and preparing a proper defense.

The Americans were now next to the Buttrick House, in the area now known as The Muster Field. From there, they had a good view of the bridge (if they had artillery, they could have made the bridge totally indefensible from there) and an obstructed view of what was going on in Concord. Over the trees, smoke began to rise, as the grenadiers were burning a cache of wooden trenchers and barrels, as well as the carriages for 2 cannon they had found. Thinking that the troops were burning the town, the Concord men pressured Barrett into ordering a march to the center.

Meanwhile, Laurie, feeling uneasy at the growing numbers of armed rebels so close to his position, sent one of the officers from Major Mitchell's patrol to Col. smith, asking for additional help. Smith's initial reply was that he thought 3 companies more than adequate to hold a bridge. And in fact he was right. If Laurie had thought through his tactical problem and looked at the position he had to defend, he ought to have been able to hold it against the much larger force for a decently long time, especially since his opponents were militia. But on Laurie's second appeal, he ordered his two reserve companies of grenadiers up the road to the bridge, but retarded their march by marching himself at their head. Several British accounts note the fact that Smith was a very fat, heavy man, whose best marching days were in 1775 long behind him. They would be too late to do anything to help Laurie, except cover his retret back to Concord Center.

Now we can look at the topography of the scene Doolittle is depicting. The Concord River and the North Bridge are the dominant features here. The current bridge is a replica, the third, I believe, of the bridge that stood there in 1775. Doolittle's engraving was the primary source for later generations so that they could rebuild the bridge pretty much as it was in 1775.

The terrain was much more open in 1775 than it is today. On the British side in particular, there are large trees now planted along the road leading to the Bridge, that were not there in 1775. Though the National Park Service is keen to replicate the 1775 environment as closely as possible, those trees are likely to stay, as they were planted as a memorial. On the British side of the bridge, there is today an obelisk marking the events. On the American side, there is Daniel Chester

French's The Minuteman statue, which is the symbol for the US National Guard.

The Concord River is fairly shallow, but in the spring, it tends to flood dramatically, with the surrounding fields often innundated especially in late March or early April. Hence Emerson's line, "By the rude bridge that arched the flood."

If you were in the middle foreground of the engraving, and walked directly out of it, you would run into the Old Manse, the parsonage for the town of Concord. In 1775, the parson was one William Emerson, the grandfather of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Parson Emerson, though he would serve with American troops later, and die of the Camp Fever the next year, on this day was trying to keep the women and children who had clustered at the parsonage calm. His biggest worry seems to have been his own wife, who apparently was close to a nervous breakdown. The troops did not enter the parsonage, though it would have made an excellent defensive bastion against raw militia without artillery, and would have enabled them to hold open the bridge, and the return route of the 4 companies of their comrades at Barrett's Farm. Doolittle may have sketched the scene from Emerson's description from a window of the Old Manse. Later, the Manse would be the home of Ralph Waldo Emerson, who later rented it to Nathaniel Hawthorne.

This copy of the engraving cuts off the far left side, which depicts two houses on the ridge just below the Muster Field. They belonged to Captain David Brown, and were occupied by his very large family. Captain Brown, at that moment, was busy commanding one of Concord's three companies of minutemen Captain Brown was a superstitious sort, and, in the years after the battle, never crossed the bridge at night without singing a Psalm tune at the top of his lungs. The houses are no longer standing, but extensive archeological investigations have been made on their sites.

The one house you can see clearly is the Buttrick House, in the center of the engraving above the bridge. Actually, it is a quarter mile from the bridge, and out of musket range. John Buttrick was a major in the regiment of minutemen from Concord and the surrounding towns, and was leading the rebel column's march on the bridge. The house still stands today.

What we obviously do not see is the Buttrick Mansion, built by Buttrick's prosperous descendants about 150 yards in front of the original Buttrick House. It today is the NPS Visitors' Center for the Old North Bridge site, and has lovely gardens. One of my favorite places on earth.

One feature ought to be noted, and that is the dry-laid stone wall, of typical New England design, which ran, and runs along both sides of the road leading to the bridge on the British side of the river. One can only opine that, had Laurie made good use of the time and manpower he had, he could have set 75 men to making a breastwork along the river bank with those stones, while a dozen more pulled up half the stringers of the bridge. No armed body could have crossed the river then, in daylight against opposition.

Along the path we see the British retreating on, which is the road that leads back to Concord Center, just a hundred yards off the right edge of the engraving, the road curved sharply south to avoid a fairly high hill with woods (now) and a stone wall near its top. Again, Laurie could have used that position to hem in any American forces that got over the bridge. Two companies along that ridge, and one in the Old Manse, and Barrett's troops would haved been stopped up like liquid in a corked bottle. Two companies of grenadiers appraching along the road, and the 4 companies at Barrett's Farm coming from the rear, and Concord Bridge could have been an ignominious defeat, rather than the site of America's first military victory. Barrett was no fool. Once he repelled Laurie, he had his forces occupy that ridge, and watched ominously as Smith milled around pointlessly on the road below, before marching back to town, abandoning Parsons and the 4 companies now returning from Barrett's Farm to the pleasure of the rebels.

And the idea of using the stone walls to make a breastwork to defend the river bank was raised by Ensign Jeremy Lister, a volunteer serving with the 10th's light company, but rejected by Laurie.

Now let us see what Doolittle is showing us. We see a lot of British troops in the road before the bridge. a few right at the edge of the bridge are firing. A few are behind them facing the enemy, but most are heading, with more or less celerity, for Concord. This is very accurate. The best way to defend a bridge is to envelop it with fire from both sides. Laurie opted for a technique called Street Firing, which sends a large volume of fire down a central channel, like a road. The platoons or companies line up one behind the other on company or platoon front. The front company fires, then files to either side and moves back to the rear of the column, reloads, and waits for their opportunity to fire and file back again. You can advance by street firing, retreat by street firing, or hold by street firing. Laurie's apparent intention was to hold. It is used in urban warfare. It could be a good way to defend a bridge,it the men are well-versed in it, and the officers know what commands to give. That was Laurie's downfall.

The British command situation at the bridge was terrible. There were three companies, each of which should have been commanded by a captain with two lieutenants supporting him. The 4th's company's captain was on detached duty commanding a large detachment that General Gage had sent to Marshfield some months before to encourge the active loyalists of that town. In his absence, the senior lieutenant, Edward Thornton Gould commanded the company, though in practice he would have sought consent from our old friend John Barker, the junior subaltern of the company, whose diary entries we looked at last April here. So that company was commanded by two junior officers.

Then there was the second company in the column, that of the 10th Regiment. Its captain, Lawrence Parsons wasn't there either. Being the senior captain in the 7 companies sent to the bridge (one has the feeling that Smith assigned the companies for the mission to be sure that his own light company commander was senior) he took four companies, not including his own, to Barrett's Farm to search. In his absence, the 10th's light company was commanded by Lt. Waldron Kelly, who was actually the junior lieutenant assigned to the company. the senior lieutenant, Edward Hamilton, apparently feigned illness on hearing of the expedition, either out of cowardice, or alcoholic indisposition. Ensign Lister, assigned to one of the battalion companies of the 10th, volunteered to replace Hamilton on the expedition, for the honor of the regiment. He was a keen young officer, with a shrewd tactical sense, but he wasn't a regular company officer of the light infantry. By the way, one of my reenacting personae was Ensign Jeremy Lister.

The company of the 47th was commanded by Captain Laurie, but since he was the senior officer present, he wasn't commanding his company, but had to leave it to his two lieutenants while he commanded the whole.

Now two extra officers were present, Captain Lumm of Mitchell's patrol, who was mounted, and acted as Laurie's messenger and go-between with Col. Smith in Concord Center since he wasn't assigned to any of the units there, and Lt. William Sutherland, who had volunteered to act as one of the pointmen on the expedition, but was, like Lister (and Lumm), a battalion company officer. Sutherland had intended to go on with just his servant to join Parsons at Barrett's Farm, but the approach of the rebels to the Muster Field earlier had made that too hazardous, so he stayed at the bridge.

Of these officers and men, few seemed to have been familiar with Street Firing drill. It was among the options available for maneouvers in the 1764 Manual, but not every regiment trained in it. One would have thought that, during the long winter in Boston garrison in 1774-1775, everyone would have been practiced in this, in case of rebel attack on the town of Boston. But this does not seem to have been the case. Barker, in his diary, seems to have no idea that Street Firing was what Laurie had in mind. Lister objected to that as the proper tactic. And Sutherland tried to countermand Laurie with the men of his own company, and ordered them into the meadows on either side of the road. Amazingly about a half-dozen of the men of Laurie's own company obeyed the strange officer, and followed him over the stone wall into the meadows. And they paid heavily for this. And these are the three officers at the bridge who left accounts, besides Laurie's official report.

Aside from unrfamiliarity with the tactic, the other damning features of its use here were that the lane in which the troops were drawn up was very narrow. You can't really tell from Doolittle, but at the time, the lane was no wider than the width of a wagon, with stonewalls on either side. It would be difficult for the lead half company (let alone full company) to fire then retire to the rear. The walls and the men behind them would prevent that. Today, the stone walls have been pushed back very considerably, and the tqactic can be executed by reenactment troops very easily.

The other factor that lead to the failure of this tactic was that the enemy had room to maneouvre on the opposite bank. Street Firing implies tht the enemy is confined to a narrow channel, and that pouring a heavy volume of fire down that channel will cause many casualties and, more importantly, disruption.

But in this case, especially on their left flank, the Americans had plenty of room to fan out from their column, and did do. This enabled them to pour a very heavy volume of fire into the troops packed into the narrow roadway. Moreover, this fanning out enabled them to envelop the British troops in the roadway. The fact that they had a 4-1 numerical superiority helped, too. Had the light infantry been crouching behind a breastwork made from the stonewalls, they could have held the bridge impervious to most of the rebel fire, until reinforcements showed up.

The troops who were the most exposed suffered the worst. First of all, the officers, on the sides of their companies. In the first company, Gould was hit in the heel. In the 10th, Kelly was hit in the arm. In the 47th, Lt. Hull received a mortal wound in the chest (he died the next day). On the flank, Sutherland took a shallow but ugly wound across the chest. Until he got back to Boston, and a surgeon's care, he was thought to be dying. The men from the 47th who went into the fields with Sutherland from the back of the column were disproportionately wounded. And in the very front company, that of the 4th, one man was killed on the spot, one so badly wounded that he had to be left there (he was, within minutes, attacked by a hatchet-wielding American who left him there to die, leading to reports that the rebels were scalping British wounded--reports that fueled genuine British atrocities later in the day, like killing prisoners in Menotomy), and one more was carried back to Concord, where he died despite Dr. Minot's ministrations.

Doolittle shows us the Americans firing more generally, I think, than the British. After Gould's half company fired, the men of the 4th could not get out of the way of the rest of the column. The men behind them could not get forward to step into their place, so they all just went to the right about, and headed back to Concord, carrying most of the 9 wounded men with them.

You can make out the leading American, who is probably Major Buttrick, who leapt into the air, crying out, "Fire, fellow soldiers, for God's sake, fire!"

Though the British fired first here (the first shot coming from one of the men Sutherland led into the Manse field) their fire was fairly ineffective. Only one company, that of the 4th, could fire without hitting their own men (except for the few men in the meadows). And it may be that the 4th was divided into two half-companies, so that only the first 16 or so men could fire. Two Americans were killed, including the captain of the leading minuteman company, Issac Davis of Acton (whose men were first because Davis, a blacksmith, made sure every man in his company had a good bayonet for his musket, and who may have had something of a premonition of his death when he marched off that morning, as he had turned back to his wife, and said, "Take good care of the children."). Three more were wounded, but that did nothing to slacken the volume of fire coming from the American side of the bridge.

So what Doolittle is showing us is the first American military victory. If it was duly recognized as such, the needless 19th century feud between Lexington and Concord as to which town offered the first forcible resistance to the Britihs might have been avoided. The Lexington men did fire back at the British, and therefore offered the first forcible resistance. But Concord was the scene of America's first military victory. Laurels enough to go around.

I'll analyze this one of Lord Percy's relief column rescuing Col. Smith's command in Lexington later. This entry is so long, it has taken most of my blogging time for the last two days already. I'll post a link back when I do it. Promise.

Tuesday, April 18, 2006

Ritual Murder, Cults, Sex Abuse: By Priests

I have a feeling this Ohio murder case is going to be very enlightening by the time it is done.

In the past, circumstances like the extraordinary concentration of pervert priests in the St. John's Seminary class of 1960 have been explained as just a product of the times. The Church was looking the other way on the issue of homosexuality in the priesthood at the time to get numbers, or the turmoil of the sexual revolution combined with the cultural currents that led to Vatican II combined to create this mess.

But what if something much darker, like a perverted homosexual cult was florishing among priests? There have been cases where the sex abuse had aspects to it that could be described as initiatory rites, like the victims were being initiated into something. I took that evidence to mean that they were being initiated into the perverted world of the sodomite priest. But what if this whole thing had some sort of overarching cult aspect to it? That would be something every Catholic ought to know about.

Watch developments in this case.

In the past, circumstances like the extraordinary concentration of pervert priests in the St. John's Seminary class of 1960 have been explained as just a product of the times. The Church was looking the other way on the issue of homosexuality in the priesthood at the time to get numbers, or the turmoil of the sexual revolution combined with the cultural currents that led to Vatican II combined to create this mess.

But what if something much darker, like a perverted homosexual cult was florishing among priests? There have been cases where the sex abuse had aspects to it that could be described as initiatory rites, like the victims were being initiated into something. I took that evidence to mean that they were being initiated into the perverted world of the sodomite priest. But what if this whole thing had some sort of overarching cult aspect to it? That would be something every Catholic ought to know about.

Watch developments in this case.

The Midnight Ride In Revere's Sworn Testimony

Paul Revere by John Singleton Copley

I, PAUL REVERE, of Boston, in the colony of the Massachusetts Bay in New England; of lawful age, do testify and say; that I was sent for by Dr. Joseph Warren, of said Boston, on the evening of the 18th of April, about 10 o'clock; when he desired me, ''to go to Lexington, and inform Mr. Samuel Adams, and the Hon. John Hancock Esq. that there was a number of soldiers, composed of light troops, and grenadiers, marching to the bottom of the common, where there was a number of boats to receive them; it was supposed that they were going to Lexington, by the way of Cambridge River, to take them, or go to Concord, to destroy the colony stores.''

I proceeded immediately, and was put across Charles River and landed near Charlestown Battery; went in town, and there got a horse. While in Charlestown, I was informed by Richard Devens Esq. that he met that evening, after sunset, nine officers of the ministerial army, mounted on good horses, and armed, going towards Concord.

I set off, it was then about 11 o'clock, the moon shone bright. I had got almost over Charlestown Common, towards Cambridge, when I saw two officers on horse-back, standing under the shade of a tree, in a narrow part of the road. I was near enough to see their holsters and cockades. One of them started his horse towards me, the other up the road, as I supposed, to head me, should I escape the first. I turned my horse short about, and rode upon a full gallop for Mistick Road. He followed me about 300 yards, and finding he could not catch me, returned. I proceeded to Lexington, through Mistick, and alarmed Mr. Adams and Col. Hancock.

After I had been there about half an hour Mr. Daws arrived, who came from Boston, over the Neck.

We set off for Concord, and were overtaken by a young gentleman named Prescot, who belonged to Concord, and was going home. When we had got about half way from Lexington to Concord, the other two stopped at a house to awake the men, I kept along. When I had got about 200 yards ahead of them, I saw two officers as before. I called to my company to come up, saying here was two of them, (for I had told them what Mr. Devens told me, and of my being stopped). In an instant I saw four of them, who rode up to me with their pistols in their bands, said ''G---d d---n you, stop. If you go an inch further, you are a dead man.'' Immediately Mr. Prescot came up. We attempted to get through them, but they kept before us, and swore if we did not turn in to that pasture, they would blow our brains out, (they had placed themselves opposite to a pair of bars, and had taken the bars down). They forced us in. When we had got in, Mr. Prescot said ''Put on!'' He took to the left, I to the right towards a wood at the bottom of the pasture, intending, when I gained that, to jump my horse and run afoot. Just as I reached it, out started six officers, seized my bridle, put their pistols to my breast, ordered me to dismount, which I did. One of them, who appeared to have the command there, and much of a gentleman, asked me where I came from; I told him. He asked what time I left . I told him, he seemed surprised, said ''Sir, may I crave your name?'' I answered ''My name is Revere. ''What'' said he, ''Paul Revere''? I answered ''Yes.'' The others abused much; but he told me not to be afraid, no one should hurt me. I told him they would miss their aim. He said they should not, they were only waiting for some deserters they expected down the road. I told him I knew better, I knew what they were after; that I had alarmed the country all the way up, that their boats were caught aground, and I should have 500 men there soon. One of them said they had 1500 coming; he seemed surprised and rode off into the road, and informed them who took me, they came down immediately on a full gallop. One of them (whom I since learned was Major Mitchel of the 5th Reg.) clapped his pistol to my head, and said he was going to ask me some questions, and if I did not tell the truth, he would blow my brains out. I told him I esteemed myself a man of truth, that he had stopped me on the highway, and made me a prisoner, I knew not by what right; I would tell him the truth; I was not afraid. He then asked me the same questions that the other did, and many more, but was more particular; I gave him much the same answers. He then ordered me to mount my horse, they first searched me for pistols. When I was mounted, the Major took the reins out of my hand, and said ''By G---d Sir, you are not to ride with reins I assure you''; and gave them to an officer on my right, to lead me. He then ordered 4 men out of the bushes, and to mount their horses; they were country men which they had stopped who were going home; then ordered us to march. He said to me, ''We are now going towards your friends, and if you attempt to run, or we are insulted, we will blow your brains out.'' When we had got into the road they formed a circle, and ordered the prisoners in the center, and to lead me in the front. We rode towards Lexington at a quick pace; they very often insulted me calling me rebel, etc., etc. After we had got about a mile, I was given to the sergeant to lead, he was ordered to take out his pistol, (he rode with a hanger,) and if I ran, to execute the major's sentence.

When we got within about half a mile of the Meeting House we heard a gun fired. The Major asked me what it was for, I told him to alarm the country; he ordered the four prisoners to dismount, they did, then one of the officers dismounted and cut the bridles and saddles off the horses, and drove them away, and told the men they might go about their business. I asked the Major to dismiss me, he said he would carry me, let the consequence be what it will. He then ordered us to march.

When we got within sight of the Meeting House, we heard a volley of guns fired, as I supposed at the tavern, as an alarm; the Major ordered us to halt, he asked me how far it was to Cambridge, and many more questions, which I answered. He then asked the sergeant, if his horse was tired, he said yes; he ordered him to take my horse. I dismounted, and the sergeant mounted my horse; they cut the bridle and saddle of the sergeant's horse, and rode off down the road. I then went to the house were I left Messrs. Adams and Hancock, and told them what had happened; their friends advised them to go out of the way; I went with them, about two miles across road.